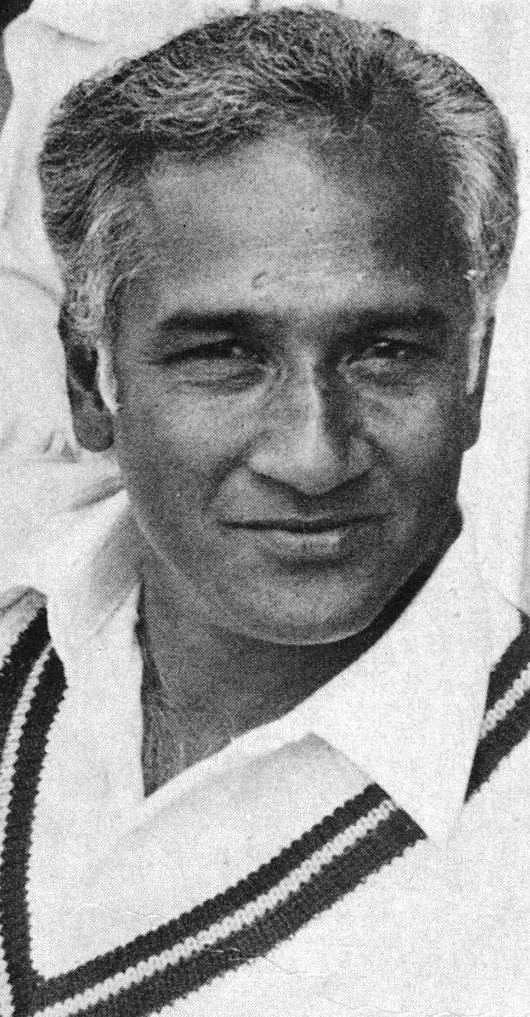

Rohan Kanhai is not only one of the finest to come from the West Indies, but he is also one of the most exhilarating artists, an artist with more than a touch of genius about his work. A Guyanan of Indian extraction, there is always some Eastern flavoring in his batting, especially in the more delicate of his strokes, like the late cut.

I will remember Rohan Kanhai more for the way he made his runs than for the runs themselves, like the time he was playing for the Rest of the World against England and picked up a highly respectable ball from Tom Cartwright on about the leg stump and deposited it over the top of the long-on stand.

It was a perfect example of both his ingenuity and the surprising power that he can put into his strokes, despite his slight, almost delicate build. On one occasion in a test, I sent down a delivery that was just short of a length but straightened off the pitch sufficiently to worry most players, but not Rohan.

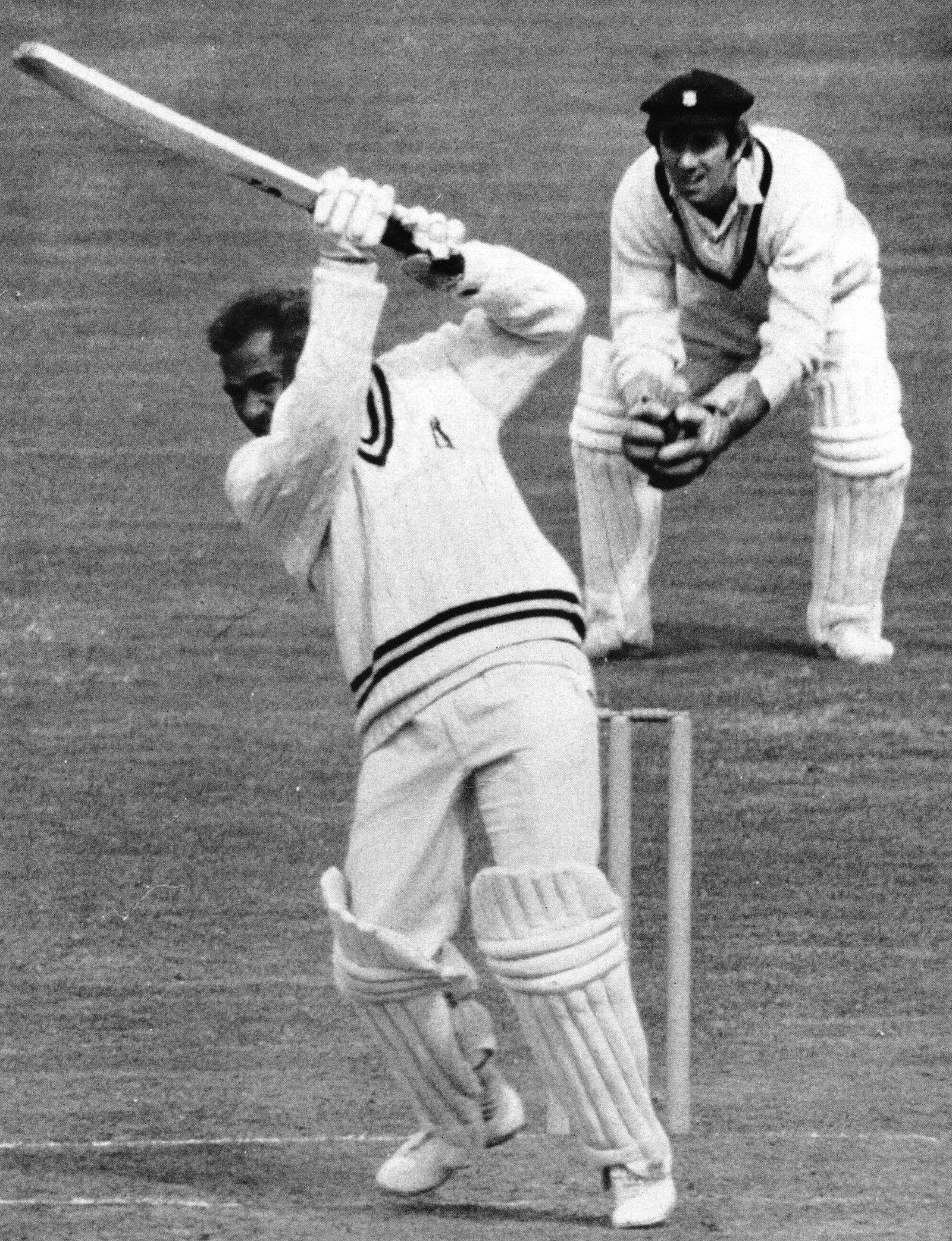

He simply adjusted his forcing backstroke, and by angling his bat, he caressed the ball past the cover’s left hand to the boundary. As with all great players, Rohan Kanhai has a sound technique to back up his very extensive repertoire of attacking shots. In his early days, some of these were almost too extravagant, and he is certainly the only person I have seen frequently hit a ball over the square-leg boundary with a cross between a pull and a sweep and finish up lying on his back.

His magic stems from a wonderful eye, lightning reflexes, footwork, and perfect timing. He has the ability to take an attack apart with a savage yet essentially civilized assault, but he also possesses the skill, the defense, and the concentration to make a five-hour test century.

Read More – Roy Gilchrist – A Violent Temper Fast Bowler

Rohan Kanhai’s long and distinguished career as an international cricketer is best divided into four distinct phases: the novice, the flashing meteor, the mature craftsman, and the captain of the West Indies. It was back in 1957 that he made his first trip to England with a West Indian side that never played to its potential and was heavily crushed in the Test matches.

In those days, he was a batsman of obvious promise and a wicketkeeper of rather less. Although he was clearly not as good as Gerry Alexander behind the stumps, he did keep in the first three Tests and played as a batsman in the remainder.

On this tour, there was no disguising his potential, but he was never given a settled niche in the order, opened on occasions, and had to be content with several flashing forties. Rohan Kanhai established himself as a world-class player when the West Indies visited India and Pakistan. He proceeded to score more runs than anyone else, including double centuries, with brilliance and inventiveness that were often breathtaking.

Any remaining doubts as to his rating among the truly great were finally dispelled during Frank Worrell’s epic tour to Australia. It was Rohan Kanhai who first caught the imagination of the Australian public with a flowing century against an Australian XI and followed it up with an even more remarkable double century in Melbourne.

Throughout the tests, he was the leading scorer and enchanted everybody with the splendor of his strokes. This represented the zenith of his power, and from then until phase three, the dazzling meteor sparkled only intermittently, and he began to slide from real greatness to become just another, better than average, Test cricketer. This was typified by his father’s labored century in the final Test against England during his third visit to this country.

By 1968, Rohan Kanhai could be said to have reached the crossroads of his career. There were many who felt that he was finished at the highest level, but he was to prove them all wrong with an outstanding series against England in the Caribbean, a renaissance that proved to be as complete as Tom Graveney‘s.

Nothing was more impressive than the way he withstood a barrage of speed in the West Indies’ first inning at Sabina Park on a pitch where the ball behaved unpredictably. His technique in stopping the shooter and the impressive manner in which he accepted the physical battering were both an exhibition of batting skill and courage.

The Rohan Kanhai comeback was largely due to a gradual change in outlook because the ability was always there. Originally, his character, like his batting, was inclined to flashes of impetuosity, but he grew up and matured. This enabled him to rethink and control the occasional outburst both on and off the field. He is a wiser, more tolerant, and more generous person who emerged to delight cricket lovers everywhere.

Apart from Test cricket, Rohan Kanhai joined Warwickshire, where he has been an enormous success in every respect, and his batting was one of the main reasons why his adopted county carried off the championship. The final accolade to a wonderful career occurred last winter when the graying, heavier, but still very active, senator of West Indian cricket was invited to captain his country against the Australians.

I thought he did well in the first Test at Sabina Park, which I saw, but subsequently, it is reported that he became rather over-defensive and the Australians finished comfortably as winners. Now he is leading the West Indies in England, and in the first Test, his side cruised to that victory that has eluded them for so long.

One of the main reasons for this win was the shrewd and positive way he handled his team. In addition to being a master batsman and a fine slipper, he has developed into a very astute skipper, with his performance at The Oval providing a classic exhibition of the art of captaincy. In April 1955, Rohan Kanhai cross-batted Keith Miller en route to a half-century. Kahani said, Keith Miller got upset at the way the 19-year-old made a fool of the cricket manuals during the Aussies’ triumphant tour of the West Indies in 1955.

I was a relatively fresh-faced boy on the British Guiana side that faced the Aussies at Georgetown that day. Miller bowled his big outswingers, and I hit them regularly to the square-leg boundary. Nobody told me that I shouldn’t do it and that I was committing the batsman’s biggest sin by hitting against the ball. That was my favorite shot, and it brought me a plethora of runs. The giant Keith Miller was completely confused.

He knew the answer to every trick in the book, but I wasn’t playing by the rules. As he got madder, I innocently threw him to the fence. At a party after the match, Miller came up to me with a rueful grin, wagged an accusing finger, and said, “The next time you play a shot like that kid, you’ll be in trouble.” Perhaps I should have taken his warning, but I felt it was too late to change when I got a few runs. And I haven’t changed, you know.

Read More: Alvin Kallicharran – A Marketing Student Turned Professional Cricketer