Cricket is a Tough Mental Game by Sanjay Manjrekar. I can never forget the moment when Sunil Gavaskar walked up to me in Trinidad in 1989. He shook hands with me and said, “You’ve become a man now.” I had scored a hundred on my previous test in Barbados, and though I was in my early 20s, it didn’t take me long to understand what he meant. The West Indies in the early ’80s were a team of giants. To score a century against them in their backyard, we needed more than talent. Gavaskar reckoned it needed a strong mindset, or what is better known these days as “mental toughness.”.

Boys couldn’t do that; only men could. After that moment, I felt taller. I was young and felt I could do no wrong thereafter. Later, I realized there were still a lot of things I could do wrong. I idolized players like Gavaskar and Javed Miandad. They seemed to work hard “mentally” and appealed to me more than the naturally talented cricketers, who, despite their gifts, couldn’t perform.

These men delivered when it counted most. Unfortunately, as a young player, I was known as a player good for just 40 runs. It all changed one evening as I watched the trials for the Bombay University team. I was a certainty, yet selector Milind Rege mentioned I needed to score a heap of runs for the team. “You have to concentrate more,” he said, and I winced.

This was a phrase that had been tossed at me repeatedly, and, frustrated, I burst out, “Everybody is telling me to concentrate. But what should I do?” Rege carefully chose his words: “As a batsman, you should try and play every delivery as correctly as possible. You should not give a single delivery less than your 100 percent application.” He was telling me to be tough mentally.

He was right, too. I scored six consecutive hundreds soon after, and in three years, I was knocking on the doors of Test cricket. But the lessons were far from over. I was too young to be educated about the “fear of failure,” something that seems to afflict several Indian cricketers. In the late ’80s, during a Deodhar Trophy match, West Zone was on a roll, and when the 45th over began, I was still waiting to bat. I was slated to go in at No. 4, but I started thinking I was in a no-win situation.

A situation Ajay Jadeja faces so often and amazingly excels at: not enough overs to make a decent contribution and great chances of failure when you have to throw your bat around. Consumed by the thought of failure, I told West Zone vice captain Lalchand Rajput of my reluctance to bat in the end overs. He agreed, but his disapproval was clear. At nets a week later in Mumbai, I smashed a ball from Ravi Shastri into the stands. Imagine my shock when Shastri screamed at me, “Why couldn’t you have tried to do that in the Deodhar game?” The news had traveled fast, and I was embarrassed. Later, Ravi took me aside and said I should look to bat whenever possible.

More outings in the middle simply meant more chances of success. I had instead avoided an inning and made my “fear of failure” obvious—in Mumbai, this was a sin. Yet I was lucky. Rege, Ravi Shastri, and Sandeep Patil would repeatedly drill into me the importance of being khadoosour, the local slang for being mentally tough. I’m not sure whether other young Indians are as lucky to be force-fed reminders of mental toughness. The Indian team certainly needs an education on the subject.

I’d like them to be described as “tough and competitive” rather than the usual “talented and skilled.”. Mental toughness is not necessarily obvious. Sometimes it is just a silent battle being played out in a bowler’s mind. During the 1996 World Cup, Javagal Srinath and Venkatesh Prasad confessed to me that since matches were often decided in the first 15 overs, it was a difficult period for them. Yet they triumphed. Like in the India-Pakistan match

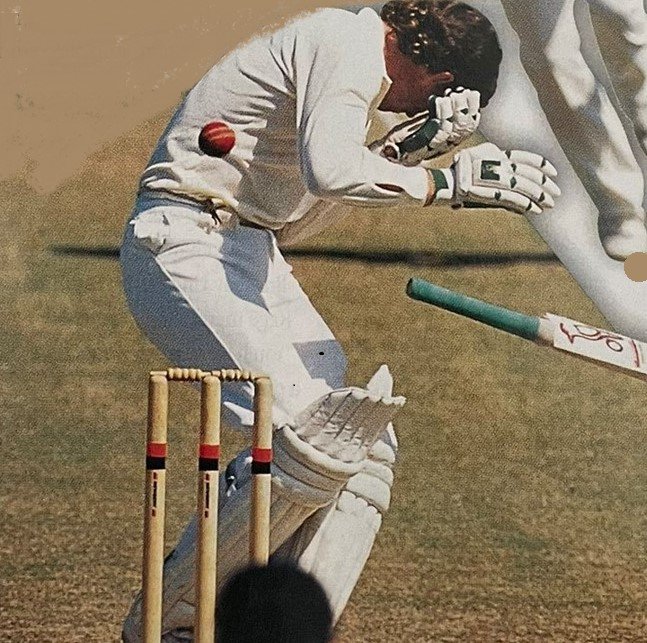

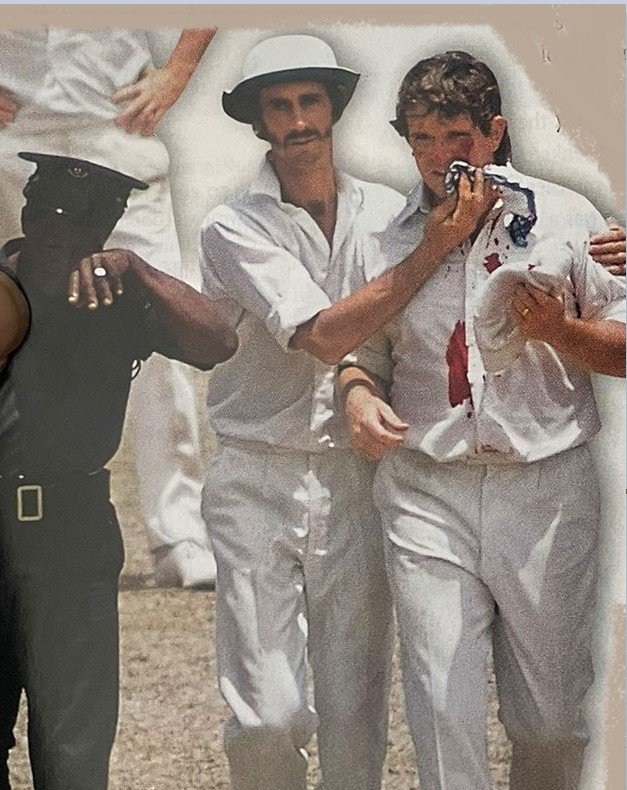

A BOUNCER HURLED AT 150 KMPH CAN LEAVE YOU WITH A BLOODIED FACE. Dean Jones’ technique failed him against England in 1989.