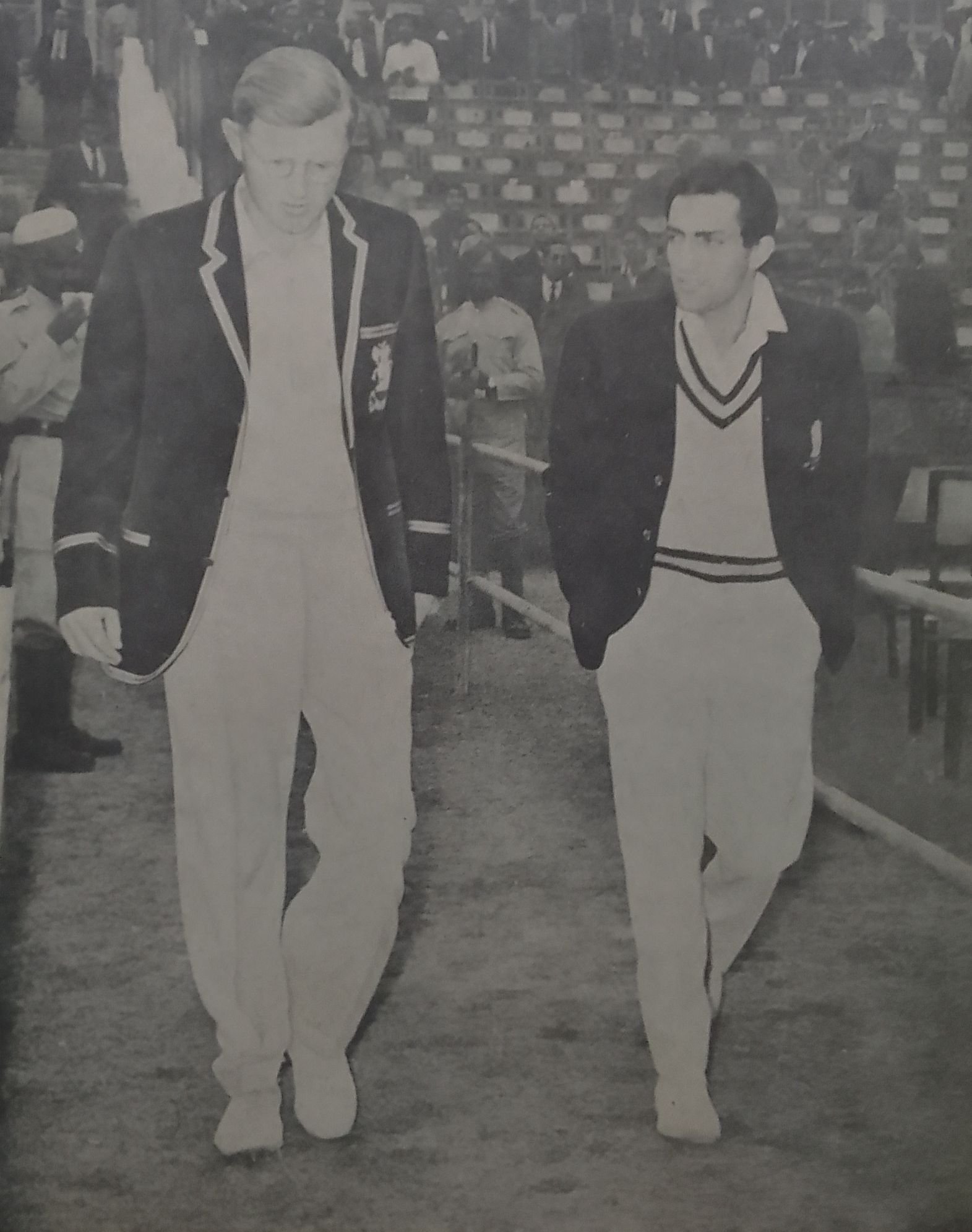

Mike Smith was born in Leicestershire, at Astley Broughton, in 1933. He was one of the most popular English captains of his generation. Michael John Knight Smith (M.J.K. Smith) played for Stamford School before 13, scoring 49 against Oakham when his main technical problem was seeing over the top of his pads. His nickname was `Blondie’ and his subsequent successes have the flavor of a strip cartoon.

Mike Smith played for the XI for six seasons and was its captain for three; at the end of an excellent school career and armed with two grade A’s, and a grade B at ‘A’ level, he attempted to enter Cambridge University. To their eventual chagrin, I imagine, St. John’s turned him down—perhaps word reached Fenner’s that he was weak on the off-side! But St. Edmund’s Hall, Oxford, was glad to have him. He embarked upon a career at his school coach’s former college, which ended with his acquiring a good second and a double blue.

Bill Packer writes of a game between St John’s and Stamford shortly after Mike’s unsuccessful attempt to gain admission. ‘When the school played their June fixture later on St. John’s ground, Mike really thrashed the bowling. He declared, captured four wickets before tea and, largely thanks to his own brilliant close catching, fulfilled his promise to the team that they would boat by six!’ A trial match was followed by another in his first match for the university (against Gloucestershire), and his first-class career, which had begun with three matches for Leicestershire in 1951, was well and truly launched.

His rugby prospered too and he played fly-half for Oxford in 1954 and 1955. Therefore, the latter year saw his partnership with Onllwyn Brace. This caused the elevation of so many interested eyes among journalists. Brace’s admiring voice can be added to other choruses: He was blind as a bat! But he was a natural player—he must have had built-in radar!’

Further, Brace, who described Mike Smith to me as the ‘perfect gentleman,’ paid him the ultimate compliment when he admitted that he was disappointed that he wasn’t a Welshman. As a general view of his rugby-playing ability and potential, he claimed that if he’d devoted himself completely to rugby he would have gone as far as he did in cricket.’ But he made it well enough to be selected for England against Wales in 1956, with Brace at scrum-half for Wales.

Nevertheless, in his first and only international, Mike Smith met the Welsh pack in a militant mood. His forwards spent the afternoon moving backward. He did not have the best games. However, uncomfortable memories of this match may be modified by justifiable pride in being the only living Englishman to represent his country in both rugby and cricket.

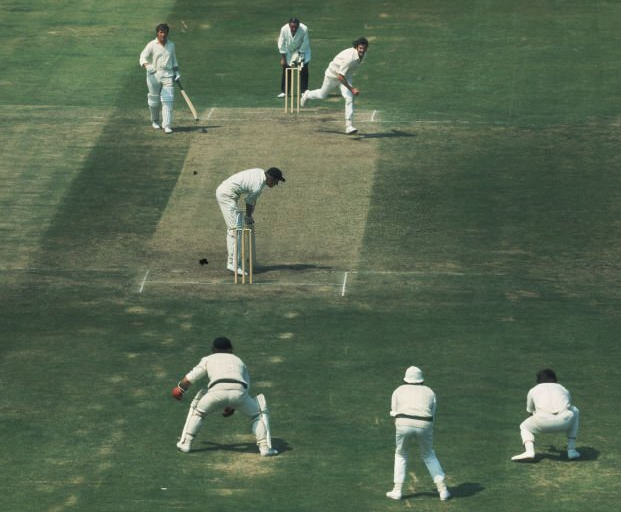

David Brown’s view of his captaincy is significant: ‘Mike Smith, for my money, is easily the most impressive skipper I have played with. Without driving, he draws more reserves out of a player than any other captain I’ve known.’ He has been consistently unobtrusive and his dealings with the press, though presenting his players in a favorable light, have never contributed to his own glorifying. No one is better qualified to judge him as a purely partisan captain than Leslie Deakins, the Warwickshire secretary.

He wrote in 1967, on the occasion of Mike’s ‘first’ retirement from first-class cricket, of the debt owed him by his county. ‘He will not be readily replaced or easily forgotten. It is certain that the very happy, sometimes successful, sometimes disappointing but never dull 11 years of his captaincy will long be remembered at Edgbaston.

It was typical of the man that he spent a considerable amount of time during his short ‘retirement’ successfully organizing the first National Club Knock-Out. As a batsman, he is not quite up to Peter May, Colin Cowdrey, or Len Hutton’s standard. However, few players’ records can compare with his for consistency over the years, as any Wisden reader can discover. It was his misfortune as an England player to be miscast, at one stage, as an opening batsman.

Wilfred Wooller, a test selector, writes: ‘My feeling is that Mike should not have been an opener, as he did not pick up the fast delivery quickly enough when he first batted in.’ Mike Smith has been adamant about the fact that wearing spectacles has not hindered his cricket career; it is interesting to consider this differing view, which suggests that his built-in radar, which aided him on the rugby field, could not operate successfully when faced with the initial onslaught of a Wes Hall or a Peter Pollock.

The criticism that he has received from time to time, of being exclusively an on-side player, seems to me to be largely unfounded; the prevalence of off-spin and in-slant bowling caused him to develop an on-side play to deal with the circumstances that faced him and those who know his batting best are scornful of such a view.

Moreover, the last innings I watched him play during the past season saw his welcome return to the first-class game and exemplified his talent without taking undue risks. Because he took a single off practically every ball, ran like a frisky colt, and scored, from the outset of his innings.

Thus, at around a run-a-minute, while his colleague at the other end, attempted to hit the cover off the ball, progressed rather slowly. To many cricket lovers, his batting in 1970 was a revelation. What a wonderful thing it would be if Alan Smith was right and his illustrious namesake was about to “do a Graveney”: to be a better batsman in his late 30s than at any time before.’

David Brown, the Warwickshire, and England fast bowler, writes of Mike Smith: ‘I think a young cricketer (and indeed any young man) could not find a better example to follow on and off the field.’

Bill Packer, his cricket and rugby coach at Stamford School, writes of his early cricketing days. He writes: ‘As a captain at school he was superb and boys of the same age have always said that they never enjoyed cricket as much as under Mike’s leadership.’

Alan Smith, the Test selector and his present county captain, writes: ‘Of course, as a person, he is quite delightful and I don’t think you will find anyone in the game who doesn’t like him. He is rarely ruffled, always cheerful, easy-going, and loyal. He frequently appears vague and forgetful, which is a major source of giddy laughter in the dressing room.

Canon Kelly, the principal of his Oxford college, called Mike Smith a modern Admirable Crichton.’ Despite the Gilbertian ring of this last panegyrical utterance, it is fairly typical of the universal affection and respect with which this quiet, kind, entertaining, and immensely distinguished sportsman is regarded.

Furthermore, his son Neil Smith also captains Warwickshire and plays in one-day Day Internationals. Also, his daughter Carole, is the wife of British politician Sebastian Coe.

In 50 Test matches, Mike Smith scored 2,278 runs at 31.63, including 3 hundred, 11 fifties, 53 catches, a top score of 121, and 1 wicket.

In 637 FC matches, Mike Smith scored 39,832 runs at 41.84, including 69 hundred, 241 fifties, 593 catches, a top score of 204, and 5 wickets.

In 140 List-A matches, Mike Smith scored 3,106 runs at 27.48, including 15 fifties, his highest score was 97* and 40 catches.