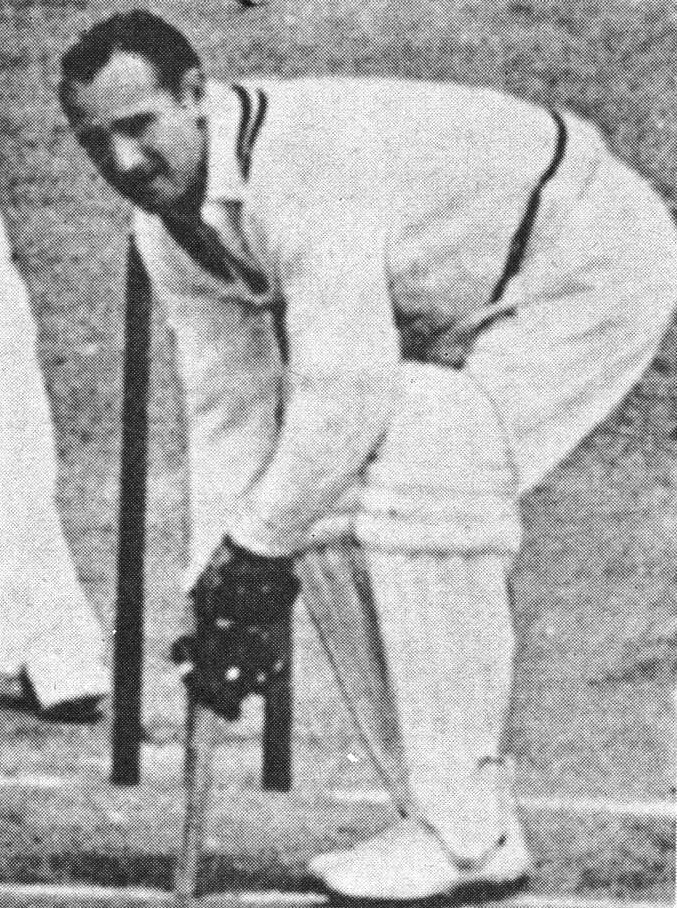

Sid Barnes, known as the No. 1 rebel of Australian cricket, enjoyed the title and, for much of his eventful life, did his utmost to deserve it. He died prematurely, at the age of 57, on December 16, 1973. Sid Barnes was remembered more for his clashes with authority and his on-field clowning than for batting and fielding to a standard that made him one of his country’s greatest cricketers.

In Test matches after World War II, he had the hardest bat to pass in Australia, including that of his captain, Sir Donald Bradman, then nearing 40 (nine years older than Sid). Whereas Bradman was always conscious of the match-winning value of quick scoring, the total of runs Barnes could make mattered more to Sid.

Their world Test record stand, 405 for Australia’s fifth wicket against England, illustrated this. Batting through a five-hour day for 88 on an improving Sydney wicket, Sid Barnes made 100 before Bradman joined him. While Sid Barnes was adding 116, his captain punished bowlers for 234 in 64 hours. When Sid drew level with 234, he was caught off Alec Bedser. With his unrivaled publicity sense, he had made up his mind to have his ‘name bracketed with Bradman’s as joint holders of Australia’s highest individual score at Sydney. In all, Sid Barnes stuck it out for 10 hours and 42 minutes, making him the first Australian to bat for 10 hours. Back-foot defense became an obsession.

Sid Barnes had the strokes to score much faster than his usual rate. His square-cut was the most powerful in the game; he hooked better than most, and he was adept at on-side placements. If he wished, he could skip along the track to kill spin bowling. His little-used drive gave the bail stunning blows.

Moreover, a brilliant hundred at Lord’s After backing himself to make 100 in the Lord’s Test in 1948, he celebrated his century by smashing 20 off five balls from off-spinner Jim Laker including two sixes over long-on. When I asked him the weight of his bat, he replied: ‘About 2 lb., 3 oz. but I don’t care what my bats weigh so long as they are given to me.’ Exuding brash confidence, his last words before going in to bat were often, ‘Hey, listen, who’ll lay me fifty bob to five? I can’t get 200?’

Cartoonist Don Badior depicted him using his bat as a bricklayer’s trowel to build a wall inside the crease. Yet Barnes qualified for greatness under the supreme test of batsmanship. His incredible ability to play all types of shots against any bowling lineup on almost any kind of wicket His batting average is 1072 runs in Tests. In his 13 Tests, he made three hundred and five half-centuries and held 14 catches, mostly hot from the bat at silly-leg, four yards from the striker’s toecaps.

Sid Barnes was as incorrigible a showman as he was impregnable as a batsman. In From the Boundary, I wrote, ‘Sometimes it seems as if this Artful Dodger of cricket would rather steal a run like a pickpocket than make an honest four with a straightforward stroke.’

In wartime, he tapped on the Army Minister’s door and convinced him that, instead of drilling in camp, he would be better employed organizing supplies of 44-gallon drums for General MacArthur’s US forces in the southwest Pacific. He vaulted a turnstile at Melbourne in 1947 because he had given his ticket to a friend who traveled 600 miles to the Test match.

Wrangles brought publicity, which packed halls for his cine camera films of the 1948 tour, including a film of the Queen inspecting the teams at Lords—taken in defiance of an MCC regulation. When a film showed him writhing on the ground after Dick Pollard’s lusty hit bruised his ribs at silly-leg, Sid commented: ‘It would have killed an ordinary man.’ He declared himself unavailable to tour South Africa in 1949, saying he could not afford to go for an allowance of £450.

After an adverse verbal report by the 1948 tour manager, Keith Johnson, a majority of the board vetoed his selection for a test against visiting West Indians in 1952. The veto was ‘for reasons other than cricket ability.’ Barnes sued for libel a baker who wrote a letter to a newspaper, assuming that the Board had good reasons for its ban. Sid claimed the letter meant his character and conduct rendered him unworthy to be a member of the Australian team. Board members called as uncomfortable witnesses had to answer probing questions. Among the truths brought to light was that the veto vote was nine to three.

Among the minority was Bradman, one of the three selectors who had chosen him. When the defendant baker withdrew his criticisms, Barnes waived his claim for damages, and the judge held that his name had been cleared. Disappointed at his inability to win back a place for the 1953 tour of England, Barnes dropped out of the New South Wales XI at the Adelaide Oval. When the fielding NSW side called for drinks, the steward was accompanied onto the field by Barnes, the 12th man.

Sid Barnes brushed players’ flannels, sprayed deodorant into their armpits, combed their hair, played a portable radio, and handed around a box of cigars. The performance amused the players, though their captain thought Barnes erred in wearing street clothes instead of flannels in readiness to field, if required. Delay to play led to the barracks shouting to Sid Barnes to get off. Statements in a book that appeared under his name in 1953 chilled the feelings of many players toward Barnes, as did taunts in a newspaper column bearing his name.

The man, who had blithely trodden on many toes, began to live on his nerves, saying he felt ostracized. Various business ventures prospered, but wealth brought worries. Finally, police reported finding him dead on a couch at his home with a bottle of sleeping tablets. Cricketers who filled a crematorium chapel heard the clergyman say that as an individualist, Sid Barnes had trodden a rocky road in a world that was hard on a non-conformist.