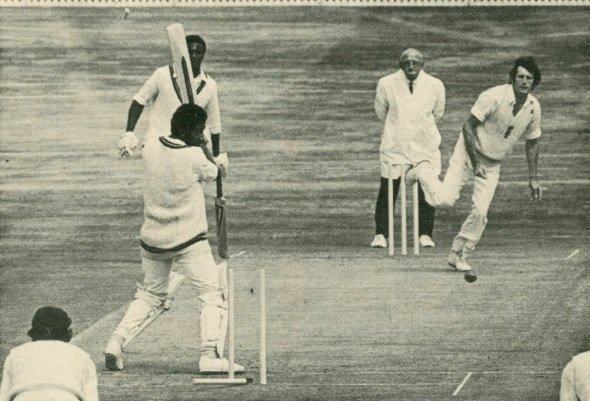

The ‘Cricket Rebel’ in Dhaka and Pakistan on the ill-advised late-1960s tour. John Snow

That week in Dhaka was probably the most nerve-racking of my life. Day and night we could hear gunfire—some of it only yards from our hotel—as the students patrolled the streets armed with rifles, seeking out people they believed to be corrupt. When found, some of these people were bound and gagged and tossed in the river to drown. At the ground itself, the work of stewards was taken over by specially selected students, and, happily, the test itself passed without incident, apart from the occasional fires on the terracing, which are part and parcel of cricket matches in Pakistan.

But it was impossible to play cricket for any purpose when thinking of one’s own safety all the time, waiting for the first sound of rifle fire, the first sign of trouble, and wondering where and how it would be possible to escape. We all felt so vulnerable out in the middle, where the nearest shelter was provided by the wicket covers.

It was hardly more comfortable off the field. The Dacca Stadium—used for all sorts of sporting activity—was a half-finished concrete shell rising out of a piece of waste ground. The dressing room was hidden under the main stand. Just four bare concrete walls without windows, dark and gloomy, lit by a single 40-watt bulb, with one door leading out to a narrow corridor and the pitch. There was nowhere for us to sit to watch the cricket, nothing to do but stay in and wait, like prisoners in a dungeon awaiting their fate.

The sanitation was primitive, the food inedible, and we existed on oranges and bananas throughout the day, thankful for the tins of relief food we had brought with us from England, until the time came when we had to push our way through the crowds to our coach and the return journey to the hotel. The few yards from the dressing room door to the coach were a nightmare as grubby hands felt over our bodies, searching in pockets for money that could be taken without opposition. There was nothing we could do, as we were forced to walk out carrying our cricket gear high above our heads. We were defenseless, and Colin Cowdrey was robbed of all his loose change. It was a relief when Dacca was behind us and we were flying back to West Pakistan. All the way to the airport we kept looking back over our shoulders wondering if any attempt would be made to stop our flight.

So far as home comforts were concerned, the ten days spent up-country at the start of the tour left much to be desired, even though we were away from the main trouble areas. Only once in those ten days did we come across a hotel where we could shower and wash from our bodies the dust and dirt collected from crossing the desert by road in a coach in which the doors and windows did not fit. The rest of the time we spent in government- or factory-owned “rest houses,” where the people did their best to make us feel welcome, although the size of the party strained their resources and equipment. I don’t think any of us ate a square meal during those ten days.

For the first game of that ten-day trek around Multan, Bahawalpur, and Lyallpur, we were forced to rise at 5.30 and take a specially chartered plane for a two-hour journey to the ground. Not the best way to prepare for a match. We were behind schedule when we arrived, and the match began late when Colin Cowdrey told the local officials that no English side ever started a game of cricket without first having a cup of tea. Two or three times the umpire looked into our dressing room asking when the game would start, but Colin insisted on tea first after our journey. He got his way. There was another cruel dawn start later for our visit to Sahiwal and the last chance of practice before the first test in Lahore. By that time we had spent a couple of days in our comfortable hotel in Lahore, and we were not looking forward to going out into the country again.

Our discomfort was even greater at 5.30 in the morning when we were presented with our coach for the two-hour road journey. One look inside was enough to have manager Les Ames appealing to the English cricket writers accompanying us for the use of a fleet of cars they had hired. The coach had been used as a cattle truck the day before—and given to us complete with all the trimmings of straw and droppings. In Sahiwal we had been booked into another Government Rest House, which had been “condemned” three years previously by Les Ames when he managed the Under-25 tour in Pakistan.

He had recommended that MCC should never visit Sahiwal again until the town boasted a decent-sized hotel. I have two great memories of the visit. One is the plate of sixteen eggs David Brown ate before going to a function where we had been warned not to eat the food. These eggs were cooked over an open fire in a smoke-filled “kitchen.”

The other one was that night—fortunately our only night in the Rest House, where it was so cold we lit fires in our rooms only to find the chimneys blocked and the smoke choking us. Despite the hardship, it was an eye-opening experience for me on my first tour to that part of the world. The fascinating but saddening life I saw seemed a million miles away from civilization as we know it at home. There were many wretched sights of living conditions, people close to starvation, and emaciated children. There was plenty to think about in the evenings when we were closeted in rooms we all thought were almost unfit for human habitation but which would have seemed like palaces to many living not 50 yards away.