John Snow was one of the most successful and well-known fast bowlers in English cricket history. He made his debut for the England cricket team in 1965 against New Zealand and quickly became known for his aggressive bowling style. In a career that spanned more than 10 years, he took over 200 wickets and helped England to several victories over top international teams.

The ultimate goal in any cricketer’s life is to play against Australia. The dream, rarely achieved, is to be the player responsible for winning the Ashes. John Snow can surely lay claim to this achievement, for much as we all admired the efforts of Ray Illingworth and his batsmen in Australia, in the end, the only way to win a Test series is to bowl out the opposition twice.

In the hierarchy of English Test opening bowlers, the tall John Snow, before the present series in Australia, stood just above Bill Voce. In 25 Tests, John Snow had 99 wickets at an average of 27.51, as against Voce’s 98 wickets from 27 Tests at an average of 27.88!

You cannot get much closer than that. Near enough, it is four wickets a Test, rather better than Statham, virtually the same as Harold Larwood and Tate, and not quite as good as Fred Trueman, Frank Tyson, and Bedser. It is difficult to know whether John Snow is not flattered by such a relationship with the great fast bowlers of the post-Great War era. However, just as it is difficult to know whether there is more in him than meets the eye or less,

Sometimes, on a routine day at Hove, nothing in him meets the eye at all. More than any cricketer of comparable talent that I have seen, he seems able to switch off completely. Others can look distracted or detached—Dexter, for one—but John Snow, in some curious manner that seems almost a Zen or Yoga technique, manages to become non-apparent.

When called upon, a pale ghostly presence goes through the motions and retires into his own cloud of unknowing. It is not simply that on these occasions, there is nothing to be desired from the effort. Every bowler knows that there are times for putting everything in and times for merely bowling a length and line. Snow’s time clock is one of his own adjustments, and disconcertingly, it bears no relation to the needs of his captain.

Most successful bowlers, regardless of the circumstances, give the impression that they like bowling or hate being taken off. Snow, on the other hand, seems, too often for comfort, to agree to bowl grudgingly, as if some liberty were being taken with his contract. This is, inevitably, more pronounced in county cricket than in Test cricket, and it has made him, on the whole, a less consistent and willing performer for Sussex than for England.

Top half-dozen Yet, for all the apparent moodiness of character, impassivity, and aloofness, he is already in the top half-dozen Test wicket-takers among English fast bowlers. Given his reasonable length of career, one would expect him to end up somewhere near Alec Bedser (236 wickets), which is not a bad place for anyone. Already, as I write, he has a useful haul of wickets from the first two Tests in Australia, where he has to carry the fast attack almost single-handed as Bedser had to in his day.

In this sense, John Snow is unlucky, for nearly all the great fast bowlers have worked in pairs. Fred Trueman and Statham last played in a Test match in 1965, which was the summer Snow played his first two Tests, one each against South Africa and New Zealand, so that they just overlapped. Since then, he has had a series of partners—Brown, Jones, Ward, Higgs, Lever, Shuttleworth, none of them—for one reason or another—staying the course or having the necessary hostility.

John Snow’s Test career took its time to blossom, with short spells when he looked a bowler of quality and pace alternating with periods when he looked moderate itself. Yet he nearly always picked up an early wicket, and he could usually make short work of the tail. There was no one clearly better than him after the departure of Trueman and Statham, though Brown was the more persevering, and Jones, Larter, and Higgs were all preferred to him on the last tour of Australia.

It was, as a matter of fact, a dismal period for fast bowlers in England, with scarcely a bowler of genuine pace or swing around and few with an even tolerable action. Then, in the West Indies in 1967–68, John Snow suddenly took on a new dimension. All over the place in the opening games, so that he was left out of the first test, he sprang into action on a cracked Sabina Park pitch to take seven for 49 in the second test.

From this time on, he was the fastest, most hostile bowler on either side, dangerous with the bouncer, but equally controlled in length and direction. Next, in Barbados, he took five for 86 and three for 39 in a drawn match. In the Fifth Test, his figures of four for 82 and six for 60 gave him a final haul of 27 wickets from four Tests, as good as any bowler has managed in the West Indies.

From this moment on, Snow has been England’s first choice as a fast bowler, though he has not always looked it around the county grounds of England. Probably he needs the stimulus of a test match to find the resources that separate him from a dozen bowlers not far short of his average form or the stimulus of being rested’ from a test match, as he was in 1969 against New Zealand, when Hampshire got the rough end of his displeasure to the tune of five for 29 and five for 51.

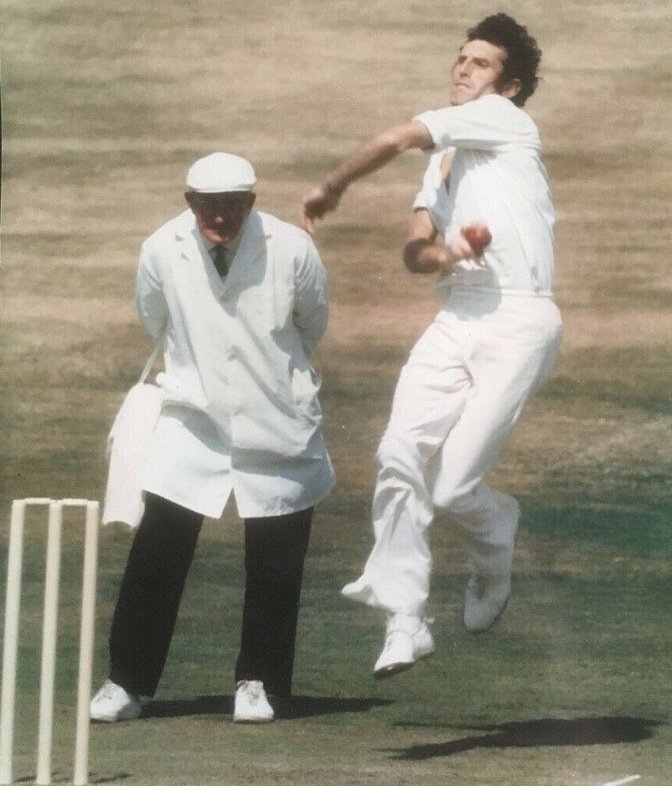

Great virtues The great virtues of Snow as a bowler are his easy, relaxed run-up, his change of pace, his late movement, and nipping off the pitch either way, but especially leaving the left-hander and the steep lift he gets from a little short of a length.

He shows more of the right shoulder to the batsman than most of the best fast bowlers did, and he has none of the classic expansion—left arm high and a right hand coming from far down, such as Fred Trueman, McKenzie, and Tyson, for example. Instead, after an initial scraping of the feet, like a dog at the door, he lopes into a gently accelerating rhythm that achieves tension and menace without evident stress.

He is not a genuine swinger of the ball through the air, in the manner of someone like Trevor Bailey or Alan Davidson, but his natural movement into the right-hander is often abruptly halted on pitching by movement the other way. When the mood is on him, he makes fast bowling seem as natural an activity as breathing, perhaps because he uses his energies as carefully as Ray Lindwall did and is really quick for no more than a couple of balls in an over.

For all his disengaged air as a third man, John Snow is a beautiful mover in the deep, quick to pounce one-handed, and fast and accurate in the throw. As a batsman, he has his moments in Test matches, both as defendant and aggressor, especially since he has been obliged to discontinue his imitation of Colin Cowdrey, left-pad thrust like a dumpling one way, head turned the other.

It could be seen that John Snow will return from this series in Australia among our most successful bowlers ever to have gone there. He is already on the way to it. Quite what people make of him is another matter, for he is neither a character nor exactly characterless. No one has found him easy to captain—though I imagine Cowdrey managed it with fewer misgivings than anyone else—so much so that perhaps the real solution would be for him to captain a side himself. It would be worth watching.

John did just that, and his haul of 55 wickets in successive series puts him firmly in the small category of truly great fast bowlers of modern times. Probably the most interesting statistic in relation to his wicket-taking prowess is the fact that approximately 20 percent of his first-class wickets have been taken at the international level.

If this has caused a few rumblings in the county of Sussex, it serves only to emphasize the point that at the top level, the present-day fast bowler has two options open to him. In an era of largely slow and easy-paced wickets, with the domestic cricket scene becoming more involved and more Test matches being played than ever before, the genuine fast bowler can easily burn himself out in a short space of time—Frank Tyson is a classic example, and shall we see Denis Lillee again?

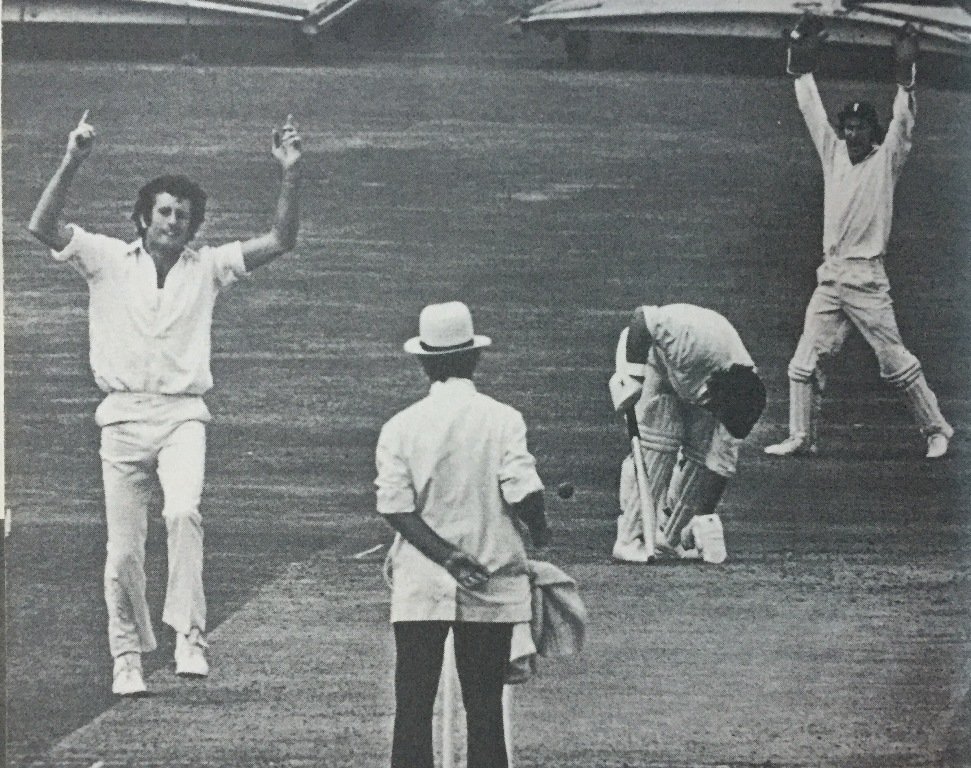

John Snow, in the face of some controversy, has perhaps saved himself for the big occasions. At 31, he remains at the very peak of his career, supremely fit, with a tremendous amount still to offer to both English and Sussex cricket. From my own advantageous spot in the commentary box, he continues to give me an enormous amount of pleasure, for to see genuine fast bowlers in full flow remains one of the great sights of any cricket field. May his long hours of hard work be duly rewarded. The celebrations continued after the Sydney win, where John Snow took 7 for 40 off 17.5 eight-ball overs. But there was also a disappointment. He recalls the moments:

The celebrations after our first victory in Sydney took some beatings. They started, naturally, with champagne in the England dressing room, then more back in the hotel, and then we celebrated at any door that opened to our knock. Nobody enjoyed victory more than Basil D’Olivera, and I shall never forget him in Sydney after we won that Test.

Nobody was more proud of the team’s performance. I am surprised that Basil still has a forefinger on his right hand from the number of times he stabbed it into the chests of complete strangers that night. He told them, “It didn’t matter who stuffed you. “No matter where they came from or what they were, they all received the same treatment, regardless of their background.

Greek immigrants, Italian immigrants, Spanish immigrants, waiters, doormen, businessmen, guests, hosts, Australians, Englishmen, cricket lovers, and non-cricket fans were left in no doubt by Basil that they had all been stuffed. I also had a disappointment that night. Somewhere along the line, I was presented with a large and unusually shaped wine bottle. I thought it would make an ideal base for a table lamp. I protected this souvenir with my life from party to party until dawn broke and my final taxi ride back to the hotel. My room was the last place I remembered it being before I realized I had left it in the back of the cab. It is probably adorning some tables in a Sydney suburb.