The 1975 Prudential World Cup will see Asif Iqbal Razvi as the captain of Pakistan for the first time. He celebrates his thirty-second birthday on the day before it starts. If Intikhab Alam omission is a real surprise and the loss of his leg-spinning is a disappointment for the crowds, at least no one could quarrel with the new appointment. The cricket world has a special affection for Asif Iqbal, and Pakistan will inherit a host of new well-wishers.

Asif Iqbal was born in Hyderabad India. He learned his cricket in India, where he was regarded as a natural batsman who could be called upon to bowl. His father, Majeed Razvi, a fine cricketer himself, died when Asif was six months old, but happily, several members of his family adored cricket and gave him every encouragement. He moved to Karachi when he was sixteen—a dramatic turn of events.

Strangely, his new cricket mentors warmed to his bowling and rather underestimated his ability with the bat. It is astonishing to watch Asif Iqbal today in full cry and to recall that he was selected for two major tours for Pakistan as an opening bowler. His first-class career was launched in 1961 against Ted Dexter’s MCC side. He took part in three unofficial Tests against the visiting Commonwealth Eleven, traveled to Ceylon and East Africa, and with the Pakistan Eaglets toured England, taking a lot of wickets.

In his first Test match, against Australia at Karachi, he took two wickets, but it is significant that batting No. 10, he scored 41 and 36. On his first major tour to Australia in 1965, he was the leading wicket-taker in the Test matches and headed the first-class bowling averages for the tour. But those with good memories who were present at the first Test match in Wellington on January 26, 1965, will confirm it marked the emergence of a new batting star.

New Zealand left Pakistan the task of scoring 259 to win but they soon found themselves 19 for 5 in the face of some magnificent fast bowling from Dick Motz and Collinge. Asif Iqbal, at No. 8, showed his mettle and followed his fine score of 30 in the first inning with a masterly and match-saving 52 not out. Unaccountably, when Pakistan came to England in 1967, he was still looked upon as a bowler rather than a batsman.

The boggy finally laid in the Oval Test match when Pakistan was 65 for 8 on the last day and about to be beaten by innings and a lot of runs, Asif produced his soliloquy, 146 in three hours, the highest score by a No. 9 batsman in a Test match. England still won the match, but Pakistan took the honors with Asif Iqbal the man of the moment.

My first memory of him is watching him field under the tree at Canterbury, patrolling that vast boundary with more zest and speed than anyone I can remember. Leslie Ames and I, manager and captain of Kent, respectively, at that time, were captivated by his uncomplicated, joyous approach to cricket as well as his undoubted natural skills, and he joined Kent in 1968. After two comparatively lean years adjusting to English conditions, everything seemed to come right in 1970.

Kent could not have won the championship that year without his glorious attacking batsmanship. Left 340 to win on the last day at Cheltenham, his innings of 109 against Allen, Mortimore, and Bissex on a broken wicket, to win the match were one of the highlights of his career. Who will forget the 91 that so nearly took Kent to victory against Lancashire in the Gillette Cup Final of 1971 and his long, sad walk back to the pavilion? Being Asif Iqbal, he was bitterly disappointed, not because of the hundred he had missed but because he felt he had failed his team. A back injury, sustained in 1964 at Sydney, keeps recurring if he bowls too much.

With so much ability, this has been a huge disappointment, but, in truth, he has the fragile frame of a racehorse, not a workhorse, and in Kent, we have now learned to use him in short bursts. He has played an invaluable role as an occasional bowler in our one-day successes. His colleagues feel that Asif the batsman, lives too dangerously. If you are sitting with your pads on, waiting to go in next, you can feel very strongly about this at times.

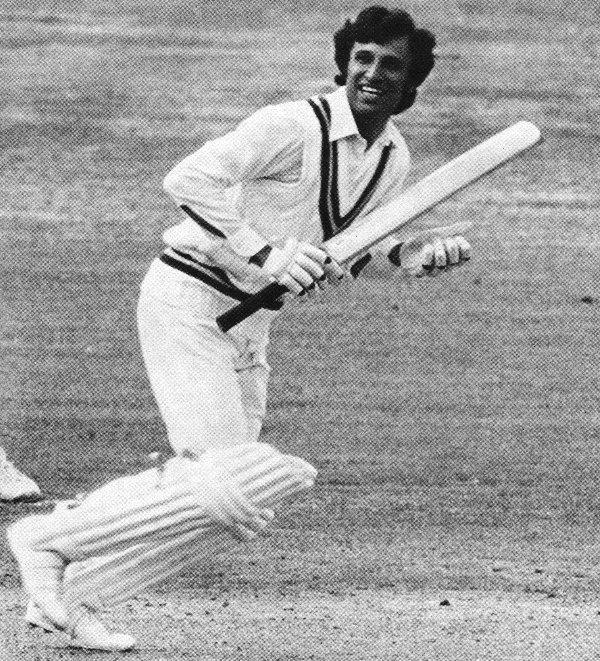

Despising all forms of defense, he has a flair for attack. Unless all guns are firing, he feels he is giving less than his best. W. G. Grace used to say, ‘I hate defensive strokes—you can only score three of them.’ This is Asif. However, in the last year or two, we have seen glimpses of a mature, more measured approach. He is reluctant to concede it but he is beginning to see that even great players in top form balance their attacks with discretion. The responsibilities of his new position will bring more discipline.

In consequence, I think we shall see Asif Iqbal emerge as a truly world-class player, his cavalier approach un-diminished, giving more pleasure than ever before. Most young cricketers would like to play like Asif. I would love to be as fleet of foot, throw caution to the winds, and hit the ball with such gay abandon. What a thrill to run as fast between the wickets! He is a tough self-critic, a man of firm principles, fired with ambitions and high ideals, which will be much in evidence long after his cricket days are over.

Asif Iqbal is now a Kentish Man, happily settled in Orrington with his wife Fahrana and two sons Omer and Hesham. It has intrigued me how a man of such a soft heart and gentle nature can be such a master of destruction on the field. As a colleague, he is generous and unselfish in the extreme and these characteristics will draw his men around him. There are too many imponderables about captaincy to assess how well he will do. It can be such an easy game when everything goes to plan.

Top-class sport is all about keeping calm under pressure. I believe that Asif will succeed because over the years his best performances have been carved out when the odds are stacked against him. Moreover, Asif Iqbal has a warm heart and a knack for radiating fun. When he smiles it is spontaneous, it is infectious and everyone around is a little happier for his touch. An old-fashioned potion, maybe, but it is a priceless gift in a serious-minded, sometimes too competitive world.

Read More – Aftab Baloch – Twinkled a While and Fading Away