From the Taj to Milton Keynes: Vic Marks, unaccustomed to reporting England victories, brings the good news from India on my third tour with England. Vic Marks on the England 1984–85 tour of India, including the day after the Madras Test win and a 15-over match in Chandigarh. The Cricketer finds himself in a unique position, reporting that England have won the Test Series and the Charminar Challenge—the one-day international series. After the death of Percy Norris and the defeat at Bombay, no one dared to predict such a change in fortunes.

Our lead was established by a magnificent all-round performance at Madras but I am assured by the redoubtable Thickness that he has covered the Fourth Test, not only with his usual plan, but also at great length, so it would be superfluous for me to dwell upon the match itself.

Instead, I must sing the praises of the manager of the Taj Coromandel Hotel in Madras. At the end of the second day, he adorned the room of Graeme Fowler, who had just completed a century, with bouquets, chocolate cake, and champagne. On the third day this fine gesture was repeated by Mike Gatting and Fowler again to mark their double centuries for England.

The manager was an ardent cricket enthusiast and, I daresay, a batsman since Foster’s wickets did not even merit a can of beer. I hope that does not sound carping; anyone who can produce free champagne in India is worth cultivating. I suspect you all imagined us relaxing around the pool amidst the warm glow of victory after the Madras Test. Not a bit of it: our itinerary (we are now on the second revised version) is very condensed as it contains virtually the same number of fixtures as the original yet is two weeks shorter.

Therefore, at 5.15 am the following morning, we boarded our coach to Madras airport before flying to Bangalore. By 9.30 am, we were in the nets preparing for the third one-day international, at 7 pm we were attending a cocktail party, and at 10 pm, bed time. The match followed a similar pattern to the previous one-day games.

We restricted India to a manageable score and then created unnecessary problems for ourselves in attaining the target; this time Allan Lamb shepherded us to victory (a sort of pun intended, I’m afraid). Again, as at Poona, the final overs were interrupted by bottle-throwing from the crowd as an English victory was imminent.

This prompted Gavaskar to lead his side off the field for 20 minutes. The following day, several Indian journalists commented that Gavaskar had overreacted, though I doubt whether they would have reached the same conclusion if one of the bottles had landed on the third man’s head. At Nagpur, slap bang in the middle of India, we lost our 100 percent record as Kapil Dev and Sunny Gavaskar joined others to guide India to victory with contrasting fifties. We were disappointed with our out-cricket after the high standards that were set in the first three games, though Jon Agnew, Chris Cowdrey, and Martyn Moxon can all remember their one-day debuts with justifiable pride.

Twenty minutes after the start, a makeshift stand collapsed like a breaking wave and we were amazed and relieved to learn that there were no fatalities. There was one other unusual incident. Allan Lamb damaged his left knee and a runner (Fowler) was summoned. After a detailed consultation between the two, Lamb hit the next ball wide of long-on, and we were treated to the rare sight of both batsman and runners scampering. We didn’t know whether to marvel at Lamb’s unbridled enthusiasm or his lack of professionalism.

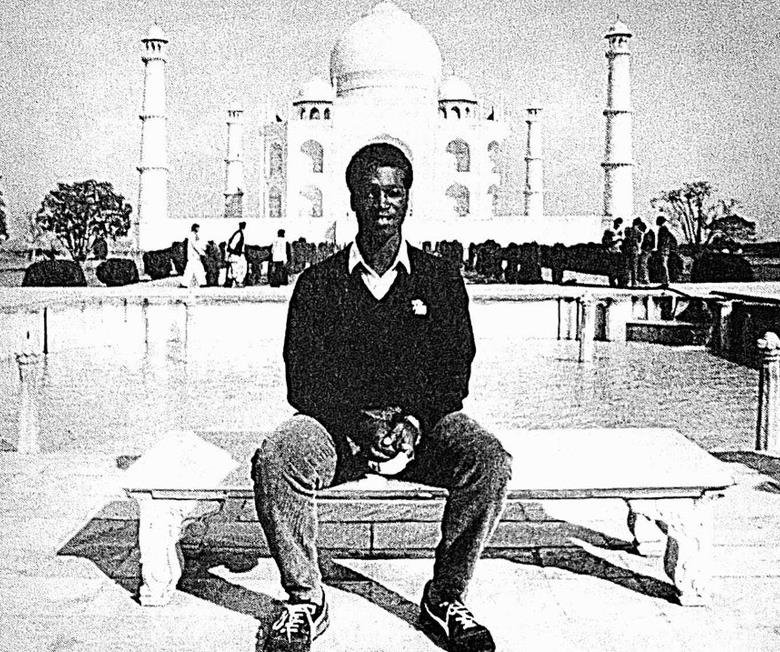

Afterward, he declared while chuckling at his error that he’d never batted with a runner before and that he did not want to again! The party moved on to Agra and another 5 am call, but this time at our own volition. None of us regretted the decision as we witnessed the majesty of the Taj Mahal at sunrise. Words fail to recapture. As the orange orb gently hovered above the hazy horizon, it glistened upon the marble dome. It was jolly pretty.

Photographers tried to capture the splendor of Mumtaz’s tomb with varying degrees of success. By contrast, Chandigarh, the Milton Keynes of India (though the signposts were more comprehensible), was not a very uplifting sight, and heavy overnight rain put the final one-day match in jeopardy. However, it was a wise decision to play despite the drenched outfield, especially since the Punjab cricket authorities had spent over £200,000 to prepare the ground for its first international game and the capacity 30,000 crowd had waited so patiently in bright sunshine.

It also provided Bruce French with his international debut, a fruitful reward for his patience and good humor in his frustrating role as reserve wicket-keeper. In a 15-over match, England scrambled home amidst the slithering, sliding and general mayhem that make such games resemble a circus act rather than a serious international contest. There are always moments of high fever, and it becomes difficult to take such games completely seriously. At Kanpur the following week, there was no such hilarity. It was the best draw I’ve ever watched, but more of that next time. Now we one-day specialists must earn our keep in Australia.

Read More: Yograj Singh: Equally talented as Kapil Dev?