Mushtaq Muhammad is recognized as an outstanding cricketer, but not always for all the valid reasons. His public image is not completely exact. He is remembered as the youngest man to play first-class cricket (at 13 and 41 days); to appear in a Test (at 15 years and 124 days); and to score a Test century (at 17 years and 82 days). When he made his first major tour of England in 1962, he was a lad of 18, but he did enough to become one of Wisden’s Cricketers of the Year.

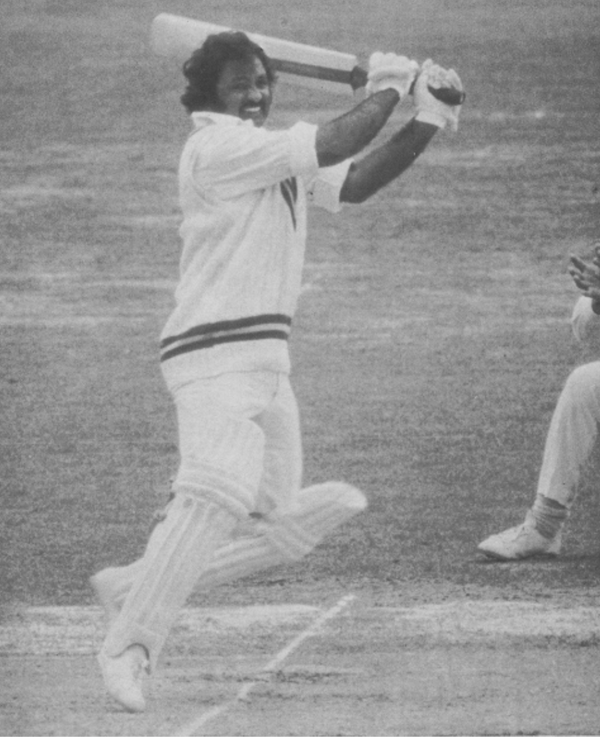

His chubby checks, ‘cherubic expression, white smile, and modest manner emphasized the impression of youth. He could be a buoyantly attacking batsman and often would switch the bat in his hands to play a ball from a left-arm spinner, in effect, left-handed. So, an idea was fostered that Mushtaq Muhammad was a boyish, carefree cricketer. In truth, he is as stern a competitor as any of his competitive brothers or as any cricketer in the world.

That first Test century at Delhi in 1960–61 was played to save a Test and the rubber against India; his second, against England at Trent Bridge in 1962, lasted over five hours and drew the match. He is, by nature and urge, a stroke maker, especially against pace bowling, which he books and cuts brilliantly and, at opportunity, will drive the wrist. Yet, in many ways, he has inherited from his brother Hanif Muhammad as the anchorman of the Pakistan batting. He, too, is deeply conscious of his family’s reputation.

In 1962, when Hanif Muhammad was troubled with a knee injury, Mushtaq Muhammad, at 18, scored more runs than any other member of the team, both in Tests and on the entire tour of England. In Pakistan’s entire history as a test-playing country, they have never taken the field without one of the sons of Ismail Mohammad and Amir Bee.

Mushtaq Muhammad was born in Junagadh, India, but was brought to Pakistan at the time of partition. All five of the brothers who grew to manhood in order of age—Wazir Muhammad, Raees Muhammad, Hanif Muhammad, Mushtaq Muhammad, and Sadiq Muhammad—played first-class cricket, once all in the same match. All were Test players for Pakistan except Raees, whom his mother thought was the most brilliant of the five and who was once told he would play against India, only to be made twelfth man.

Mushtaq Muhammad is superbly technically equipped with a sharp eye, instinctive identification. of length, nimble footwork, an innate sense of timing, and the striking power of a compactly built and muscular 13-stone man. He is a fine and frequently brilliant batsman in bowling. Under all his skills lie determination, concentration, and reluctance to get out, which mark a good professional. All this might suggest that Mushtaq Muhammad is a batsman who is pure and simple.

On the contrary, there is barely a better leg-spinner in the world. He is more accurate than most of that kind, genuinely spins the ball, and hides his googly well. Only two current wrist-spinners, Chandrasekhar and Intikhab Alam, have taken more than 40 wickets in Tests. His ability is such that often one wonders whether, if he were not a good batsman, he might not be substantially effective solely as a leg-spinner. While he has scored over 30,000 runs at an average of about 42, he has taken nearly 800 wickets at 23. When he first came to England with the Pakistani Eaglets of 1958, at the age of 14, he kept wicket.

Since then, he has been a nimble fielder in the covers and a safe catcher close to the bat. Mushtaq Muhammad was already a mature cricketer at first-class and test level when he joined Northamptonshire in 1964 at the age of 20. While he was qualifying for championship play, he won the 1965 single-wicket tournament at Lord’s. He has made two centuries in a match quite beguiling, and he won the Gillette Man of the Match award.

Now, he has played in 36 Tests, more than any other current Pakistani except the severely-deposed Intikhab Alam. His Test batting average is 42.27, exceeded only among contemporary Pakistani players by a mere 19 by his younger brother, Sadiq Muhammad. Once the impression of Mushtaq Muhammad as a light-hearted cricketer is dispelled, he becomes one to be savored. Before he faces any ball, he gives his bat the Muhammad family twirl, and then, sternly jutting, he is prepared to face whatever the bowler may deliver.

Whether he attacks or defends, he is an entertaining batsman to watch because he is so fluid in movement, so balanced, adroit, and essentially aggressive. His resistance is neither graceless nor lacking in imagination. In the most dogged innings, he will identify the punishable ball and demolish it with a splendid punitive stroke. Northamptonshire hired wisely when they engaged Mushtaq Muhammad. Next year he has a benefit, from which, if his county’s cricket followers are just, he should do well. Yet, he still has at least ten years of effective cricket in him. Indeed, it may be that we have yet to see the best of him.

Read About: Shujauddin – Fighting Gusty Pioneering Test Cricketer