Like many great Asian batsmen, Javed Miandad was immense on his own pitches. However, in his case, he was also very versatile and skilled enough to make Test hundreds when the ball was behaving very differently in Australia, England, and the Caribbean. Javed Miandad was spotted at an early age by Mushtaq Mohammad as a great player in the making. He seemed to have been born with good technique.

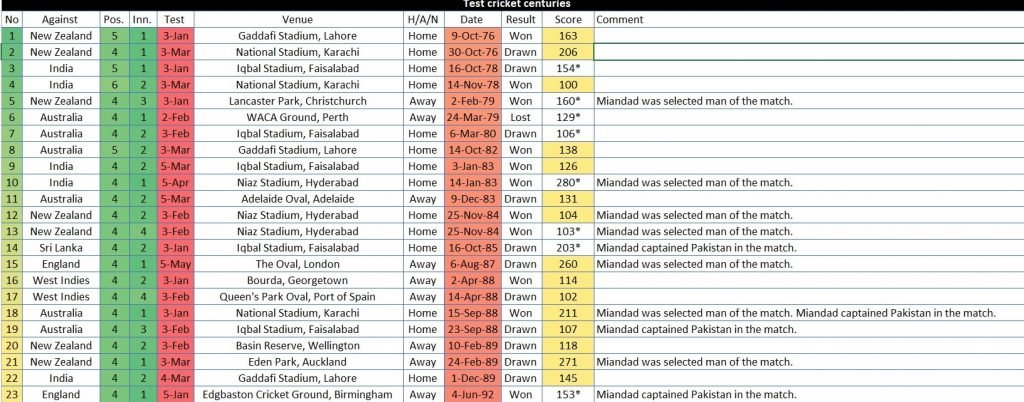

Javed Miandad scored a century in his first Test match against New Zealand in 1976 and then a brilliant double century in his third. He was still in his early twenties when he scored centuries against Richard Hadlee in Christchurch and Rodney Hogg at the bouncy track of WACA Perth. So, there were more than 2,000 runs in a championship season for Glamorgan.

Javed Miandad was the superstar batsman at the World Cup that Pakistan won in Australia and New Zealand in 1992. He was making runs in every match but one, including half-centuries in the semi-final and final, when his partnership of 139 with Imran Khan laid the platform for victory over England. Eventually, Wasim Akram two wickets on successive balls changed the whole game, and Pakistan lifted the trophy for the first time. Imran Khan had asked his players to fight like cornered tigers at that tournament, and no one fought harder than Javed.

Javed Miandad was the superstar batsman at the World Cup that Pakistan won in Australia and New Zealand in 1992. He was making runs in every match but one, including half-centuries in the semi-final and final, when his partnership of 139 with Imran Khan laid the platform for victory over England. Eventually, Wasim Akram two wickets on successive balls changed the whole game, and Pakistan lifted the trophy for the first time. Imran Khan had asked his players to fight like cornered tigers at that tournament, and no one fought harder than Javed.

If the art of batting is allied to the ability to watch the ball closely, then Javed was an absolute master. He plays the ball right in front of his face when the instinct of most people is to duck their heads behind their hands. There was none of that with him. He watched the ball right onto the bat and knocked it down, a model of control. He was brave and courageous. There was no fear in his batting.

His unorthodox game was, in fact, ideally suited to one-day cricket, a format that was just developing into a global product when he arrived on the scene in the mid-1970s. Therefore, he actually played in each of the first six World Cups between 1975 and 1996. A testament to his talent and durability. He had quick feet, supple wrists, and a great facility for maneuvering the ball into the gaps. A special and vital skill in the middle overs of a one-day inning.

He was a master at letting the ball come to him, playing it late, and using its pace to his advantage with neat deflections into the gaps. Javed cottoned on at an early stage that it was not always necessary to bludgeon the ball. He must rank as one of the best and earliest ‘finishers’ in one-day cricket.

His one-day record does not look particularly striking to today’s eyes, but when he retired in 1996, only Desmond Haynes had scored more runs in ODI’s, and few could better his average of 41.70. His clever approach to pushing the balls into the gaps and maintaining the run rate makes him an ideal batsman in that form of cricket.

What is especially notable, though, is how he performed in matches Pakistan won when chasing. Javed Miandad finished unbeaten in almost half his innings and averaged 66.24. His most famous feat in this regard, and one for which he is as well remembered in Pakistan as for anything else he did, was hitting a six off the last ball of the match, when four were needed, from Chetan Sharma to win an Asia Cup final in Sharjah.

He may have been a shot-maker by instinct, but he could play the longer game, as his Test match résumé clearly shows. His 8,832 runs at an average of 52.57 from 124 matches remain the most for Pakistan; Inzamam-ul-Haq failed to match him by only two runs. Therefore, Younis Khan beat the records a few years ago. And it should be remembered that runs were not as easy to come by in the 1980s as they were later, when pitches and pace attacks became more docile.

He may have been a shot-maker by instinct, but he could play the longer game, as his Test match résumé clearly shows. His 8,832 runs at an average of 52.57 from 124 matches remain the most for Pakistan; Inzamam-ul-Haq failed to match him by only two runs. Therefore, Younis Khan beat the records a few years ago. And it should be remembered that runs were not as easy to come by in the 1980s as they were later, when pitches and pace attacks became more docile.

There were only four individual test scores of more than 250 during that decade, and Javed made three of them. His ten-hour 260 at The Oval in 1987 firmly killed off our chances of leveling the series. His record against the West Indies, the powerhouse of that period, was understandably mixed, but he played a big part in an epic series in the Caribbean in 1988. The memorable series in which Pakistan became the first visiting side to hold their own, earning a 1-1 draw.

Javed scored a battling hundred in the match Pakistan won in Guyana and another in the fourth inning in Trinidad as his team successfully held out for a draw by batting out 129 overs. They actually needed only 31 more for victory when the match ended with them nine down. His unpredictability was probably one of his greatest strengths. Ray Illingworth, my first captain at Leicestershire, used to like to give himself an exploratory over just before lunch, just to see if the pitch was taking a turn, and confident in the knowledge that batsmen were unlikely to take risks at such a juncture.

On one occasion against Sussex, however, he got a rude shock when Javed Miandad, who had a spell with them in the late 1970s, saw this merely as an opportunity and promptly whacked him back over his head three times. Illingworth did not bowl again in the inning. This would have incensed Illy, and not just because it ruined his lunch. But then, needling opponents—and sometimes even teammates—was Javed’s specialty.

Many never had any gripes with him, but plenty of people did, including most famously Dennis Lille, with whom he once very nearly exchanged blows in a Test match at the WACA. He also played a part, as Pakistan captain, in stirring the pot after Mike Gatting’s spectacular falling-out with umpire Shakoor Rana at Faisalabad in 1987.

Which led to the loss of a day’s play. He was also captaining Pakistan on the 1992 tour of England, on which allegations of ball-tampering left the teams at loggerheads. If trouble was in the air, he could generally be counted on to get involved, and many English were sure it was a deliberate ploy. He was a big competitor with a combative spirit who likened cricket to war.

But Javed Miandad also deserves to be remembered as one of Pakistan’s best captains. He often stood in when Imran was not available, and despite therefore being without the team’s best all-rounder, he had a good record, leading Pakistan to as many Test wins as Imran himself. If Imran was the principal architect behind Pakistan’s rise in the 1980s, Javed was not far behind him. His records are marvelous in all forms of cricket.

See Miandad stats on cricinfo.