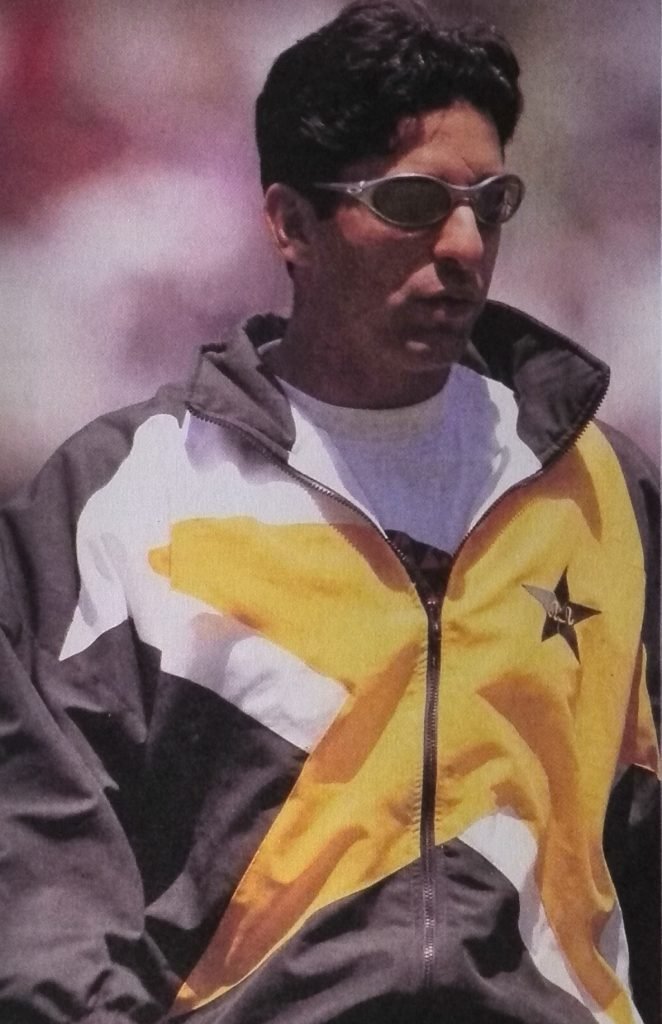

It is indisputable that Wasim Akram is the greatest left-arm fast bowler there has ever been. At his peak, there was no question that he had the speed to trouble the best batsman in the world. But he also used the ball—new or old—with rare skill.

For some reason, top-class left-arm pacemen have been relatively scarce, and only Chaminda Vaas of Sri Lanka, Zaheer Khan of India, and the Australians Mitchel Star, Mitchell Johnson, Alan Davidson, and New Zealand Trent Boult have, like Wasim, taken more than 150 Test wickets.

None can match Wasim’s haul of 414, on top of which, amazingly, he took 502 wickets in one-day internationals in both spheres at an average of 23. He was every bit as clever as the cleverest of wrist spinners; he had a magician’s hand. Wasim was outstanding because of his ability to swing the ball in either direction, by some distance, and apparently at will. He could also use the old ball in a way few others had ever managed—what we know now as reverse swing.

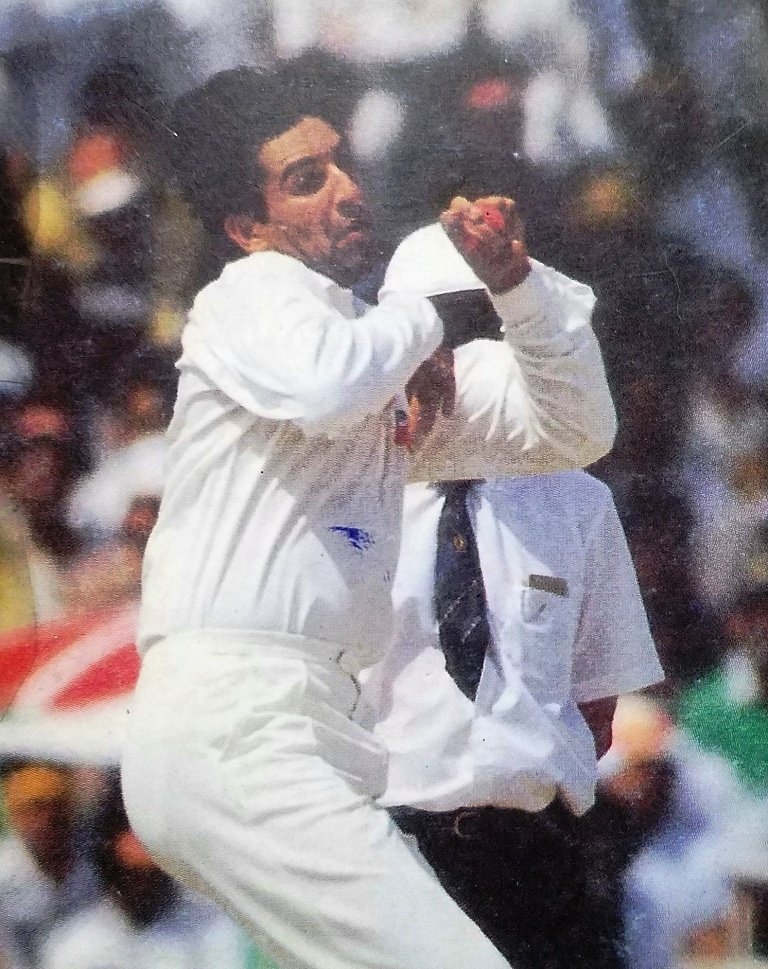

He bowled at a real pace with the new ball, but would often keep his opening spell quite short, wait for the ball to be roughed up slightly, and then return. And that’s what made him and Waqar Younis, his younger ally, so lethal. The traditional approach had been to use the new ball for swing and seam.

But with the Pakistanis—starting with Imran Khan and Sarfraz Nawaz before Wasim and Waqar came on the scene—it was a very different game. While there was nothing wrong with how Wasim and Waqar started an inning, certainly if the ball was going through, they knew, and their opponents soon enough came to know, that they were even more effective when the ball was older.

Their opening spells therefore served as preparation for the more dangerous phase of the game, with them bowling a fair few bouncers with the express purpose of abrading the ball. Then, later, they would keep the ball pitched up, giving it a chance to swing in either direction.

The reverse swing in their hands was an absolute phenomenon. There is probably an optimum speed for pure reverse, and they had it. However, whatever the full explanation, there were claims from some quarters that the ball was illegally tampered with to accelerate the roughing-up process. They were the finest exponents of reverse swing, and Wasim was ahead of Waqar.

Wasim Akram, 6 feet 5 inches and strongly built, varied his angles brilliantly. He used to go over the wicket and around as the situation demanded. He had such a quick arm that it was doubly hard for anyone new to the crease to pick up an early sight of the ball (hence, perhaps, his record four international hat-tricks).

Wasim Akram had various other idiosyncrasies, which hardly helped matters for the batsman. Such as running up behind the umpire before jumping out of delivery and hiding the ball in his hand to prevent the batsman from getting any clues as to which way it might swing. Wasim was a tougher proposition than Waqar, I believe, because he moved the ball a little more in both directions and with equal dexterity either way. Waqar tended to move the ball more into the right-hander and less away from him.

Personally, England was more troubled by left-arm pacemen and found it harder to line them up. Typically, they’d try and take the ball away from a left-hander from an off-stump line, and someone like Wasim had the ability to then bring it back in, bringing stumps and pads into play.

When they had the old ball going as they wanted, Wasim and Waqar had the power to trigger some remarkable batting collapses, some of which I witnessed at close quarters in the later stages of the 1992 Test series in England.

At Headingly, England saw plenty of partners come and go as we slumped from 292 for two to 320 all out. However, Waqar Younis caused most of the damage, while at The Oval, we lost our last seven wickets for 25 in the first innings and five for 21 in the second. Wasim Akram to the fore both times.

Although we lost the series, we won the first of those two games, though not without difficulty, as Wasim made us fight for the 99 runs we needed in the final inning. He gave us nothing. David Gower batted more than two hours for an unbeaten 31, and it was one of the toughest, most fraught passages of play ever experienced.

Wasim had also gotten the better of England a few months earlier with a man-of-the-match performance in the World Cup final in Melbourne. His late hitting for 33 off 19 balls ensured Pakistan a competitive total, and he later took the crucial wickets of Ian Botham, Allan Lamb, and Chris Lewis, two of them for ducks.

Moreover, in 1994, along with Waqar Younis, he bowled out Sri Lanka for just 71 runs in the 3rd Test match at Kandy. He took 4 for 32 and 1 for 70 to deliver the series win of 2-0. As that game illustrated, he could be more than a useful batsman.

While you would hardly back him to bat for your life, he could be suitably dangerous if the requirement was hitting the ball into the stands. He managed to hit a Test match double century against Zimbabwe pretty much doing that, massively hitting 12 sixes and 22 fours in an unbeaten 257 at Sheikhupura.

Perhaps a more creditable effort was a second-inning century in Adelaide, with his side in trouble. Wasim was largely uncoached until he got into the Pakistan side. He was discovered when he happened to bowl in the nets for Javed Miandad. He immediately realized the great potential of this young boy.

Wasim Akram was fast-tracked into the national squad at the age of 18. Because he knew so little about the world that he was unaware he would be paid! He took ten wickets in his second Test match in Dunedin in 1985. On that tour, his lethal pace struck the head of Lance Cairns, who was batting without a helmet. Luckily, he survived; otherwise, it was a brave decision to bat without a helmet.

Moreover, in the 1986–87 ODI series in India, he struck the head of Srikanth, and he was badly injured. Srikanth was considered a very aggressive batsman in those days. However, after this incident, he could not regain that confidence and was literally a bunny for Wasim Akram. On many occasions, he used to crush batsmen’s heads or toes. Perhaps David Boon and Phil Tufnel were so lucky to survive serious injuries from his bowling.

His cricketing education was greatly accelerated by spending several seasons with Lancashire, whom he helped win several one-day trophies. Pakistan has rarely been free of confusion, controversy, or allegations of corruption, and Wasim’s reputation was among those tarnished by the Abdul Qayyum report into match-fixing in Pakistan, published in 2000, which barred him from the national captaincy.

Wasim Akram Profile at Wikipedia.