Peter Hook considers the tiger’s talents of Pakistan’s Inzamam-ul-Haq in 1992. Then cometh the moment, cometh the man.’ If Inzamam-ul-Haq wasn’t acquainted with the actual phrase, he certainly appeared to understand the message. The 22-year-old was, in fact, left with little choice.

Painfully slow innings by Imran Khan in both the World Cup semi-final against New Zealand and the final against England, exacerbated by the continued failure of Salim Malik, meant that the stage was set for heroic deeds and Pakistan was fortunate that it had entrusted its future to one of the most gifted youngsters in world cricket.

Imran Khan and Javed Miandad had been the foundation stones upon which past World Cup challenges had been mounted and yet their undoubted class and acumen had never secured a final place in the previous four Cups. That was about to be extended to five tournaments when, with just 15 over’s to go in the semi-final against New Zealand at Eden Park, the Pakistanis still trailed by 122.

Imran Khan and Salim Malik were out, Javed Miandad wasn’t able to find the boundary and the Pakistani tail was notoriously fragile. It was at this point that the tall, boyish-faced Inzamam-ul-Haq appeared. There was little in his earlier World Cup record to justify Imran’s exalted pre-tournament praise of the youngster, but he had scored two centuries and two half-centuries in his first two limited-overs series against the West Indies and Sri Lanka.

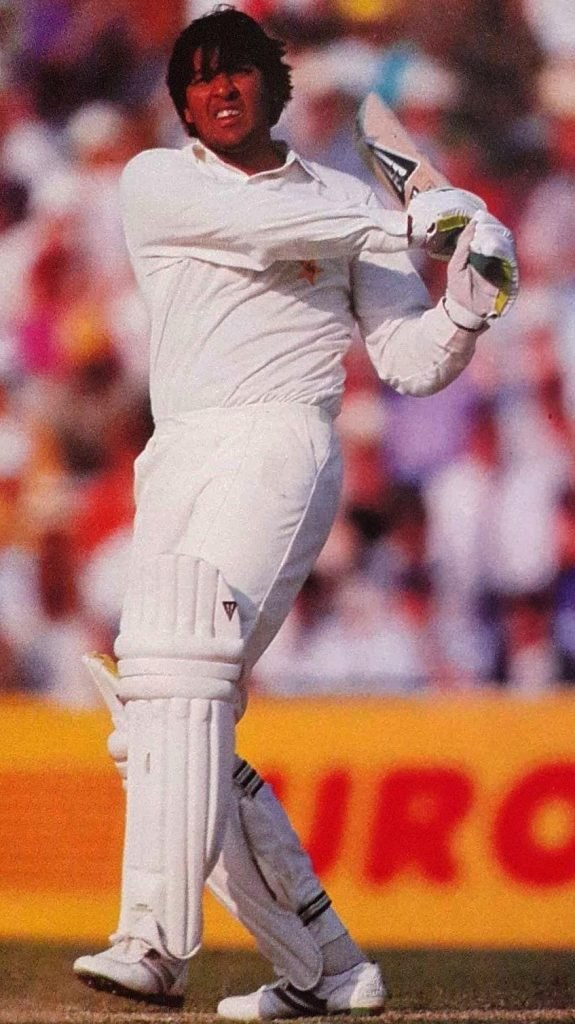

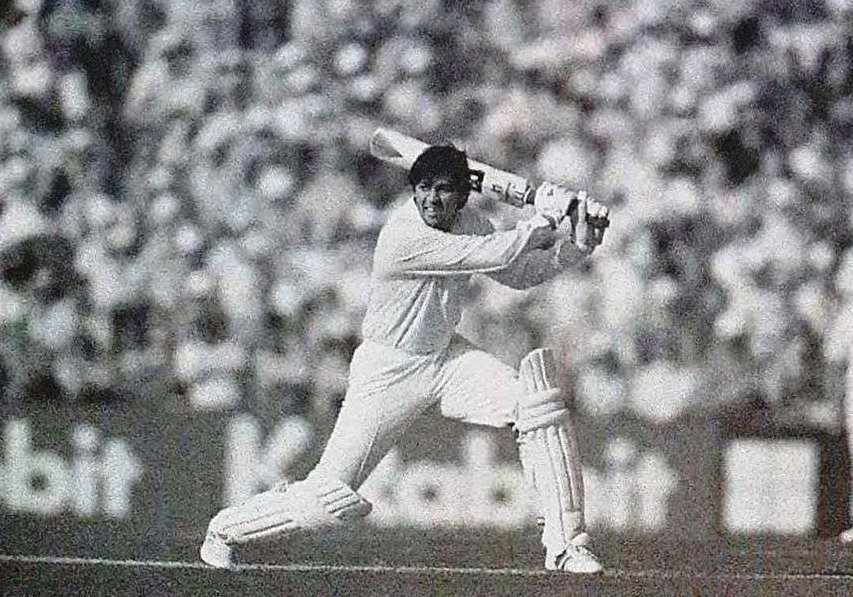

He had shown glimpses of his class during a fine 48 made against South Africa at Brisbane Gabba, so with Javed Miandad at the other end, there was still a flicker of hope for Pakistan. At the crease, Inzamam-ul-Haq gives the impression that his bat is too small. His stance is awkward and slightly stooped and it is only when he starts playing his shots that his fluency becomes apparent.

He also has the great ability to appear totally nonchalant about his batting, which takes some doing when you have Javed Miandad lecturing you every five seconds! But Miandad knows what he is doing. The wizened old pro appreciated that Inzamam was his previous chance and didn’t want him to repeat innings against New Zealand in Christchurch when a magnificent hook off his face was followed by a loose defensive shot that only helped the ball onto his stumps.

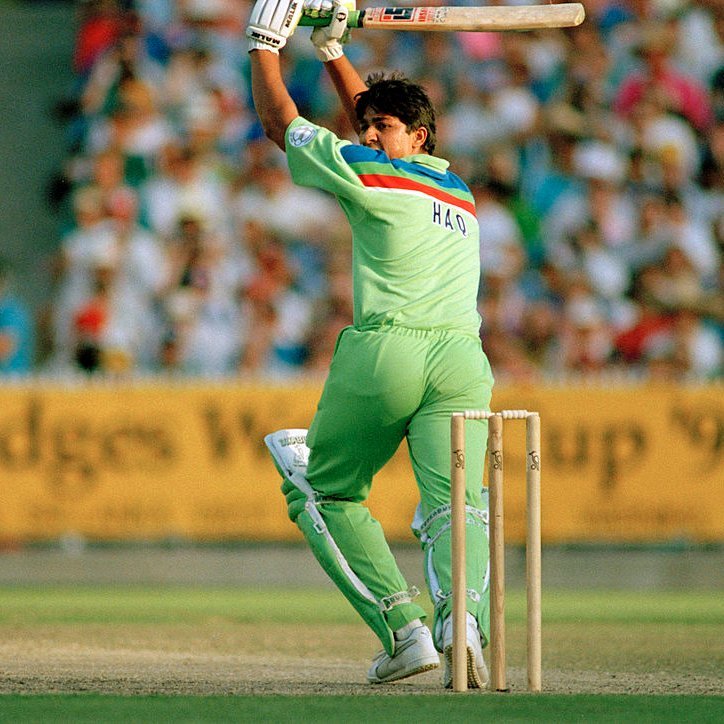

Inzamam is particularly strong on the leg side but the stroke of the semi-final was an orthodox lofted o into a howling northerly, which still managed to clear the fieldsmen and the boundary. The small Eden Park ground favored Inzamam’s stroke play, but his innings of 60 runs off just 37 balls weren’t in any way a crude affair, and he rightfully deserved the Man of the Match award ahead of Martin Crowe‘s imperious innings of 91.

The fact that the Kiwi skipper was one of the best players during the 1992 World Cup 1992 only highlighted the quality of the Pakistani’s breath-taking innings. Inzamam left the scene in the 45th over—to yet another run-out—but by that time he had taken the Pakistanis to within 36 runs of victory, and with 32 balls to go, not even a mild attack of hysteria could prevent the visitors from proceeding to Melbourne for the final.

After the game, Martin Crowe, crestfallen but still one of the most magnanimous players in the game, conceded, ‘It was a superb knock,’ while Australian and English journalists began practicing a name that made the previous pronunciation hurdle for the Australian summer – Venkatapathy Raju – seem like kindergarten English.

“Imran Khan reminded journalists after the game that he had said before the World Cup that Inzamam-ul-Haq was ‘one of the most talented cricketers I have seen”.

But the Pakistanis have promised so much over the years without properly delivering that even the most faithful of followers could be forgiven for being skeptical. Inzamam-ul-Haq’s rise to fame followed the now-usual practice of Imran talent-spotting: ‘I heard his name a few times. We had nets and I saw him once, and the way he faced Waqar Younis, he was in my team,’ Imran explained. ‘Every other batsman, including the regular Test batsmen, was beaten three times out of six balls, but he played Waqar like a medium pacer.

He played a couple of shots off his hips, which went off the ground. I only ever saw Vivan Richards play like that. `So for me, he was in. I knew for as long as I was going to play, I’d back him.’ And such is the way of Pakistan cricket selection that suddenly the Multan batsman forced players of the pedigree of Shoaib Mohammad out of the side.

Imran Khan proved how astute his talent-spotting was when the new recruit hit a classy 60 against the West Indians, followed by two centuries and a half-century against Sri Lanka in 1992, on their pre-World Cup tour of Pakistan.

Imran was as much impressed by the unflappable temperament of his protégé as he was by the range and timing of his stroke play, which perhaps explains why Imran alone seemed unperturbed by the fact that with just 10 over’s to go in the World Cup Final at the MCG, Pakistan had reached only 163. Whereas Imran had held Inzamam back to number six in Auckland, he promoted him ahead of the vastly more experienced Salim Malik at the MCG. This is a true reflection of Imran’s confidence in the youngster’s ability to handle the pressure cooker and the tension of the big match in the final.

Even his arrival at the crease—hatless and helmetless, which was the same way he had faced Ambrose and company on his international debut late last year—inspired confidence, and he didn’t disappoint either his captain or the 87,000-strong crowds.

He started with a delicate late cut for four off his first ball from Illingworth and then followed with another cut for three. He was just as effective against DeFreitas and Botham, making Imran work hard between the wickets. It was noticeable that while Imran kept on finding the fieldmen, the pupil found the spaces.

They had accelerated the scoring rate to eight overs for their brief, but productive, partnership when Imran tried to hit Ian Botham out of the ground, only to find Illingworth on the boundary. Pringle was able to tame Inzamam at the end of the innings, but not before the novice had created a momentum that Graham Gooch was unable to halt.

Inzamam-ul-Haq’s innings of 42 off 35 balls were an innings of a nerveless pro. Imran had said immediately prior to the final that Inzamam was ‘one of the most talented players I’ve seen, with one of the coolest temperaments’, but to see such ice-like precision made the comparisons with Sachin Tendulkar seem suddenly valid. His early days yet but his ability to dominate on the slow Eden Park wicket, augurs well for his summer in England. He made the previously unconquerable Kiwi medium pacers look precisely what they were—decidedly medium pacers.

Inzamam hits through the line, not relying on the pace of the wicket to score his runs, though the deftness of his deflections at the MCG showed he has all the subtleties as well. The tour of England, with or without the guiding hand of Imran, is a far greater test for Inzamam. He isn’t as sheltered as perhaps Imran would have the world believe because he was a member of Pakistan’s Youth World Cup side, which lost to Australia in the final of the inaugural tournament in 1988.

He has also been a prolific performer in Pakistan’s domestic cricket (his tally of 1,645 runs at 60.92 for Multan in 1989–90 was just four runs short of the record aggregate), so a tour of England should not be too awe-inspiring. He is far more confident with his bat than with his English, but it seems inevitable that he will proceed to the league or even county cricket if he has a successful summer in England.

He is a useful, if somewhat ungainly, left-arm spinner and completes his versatility by being able to throw with either arm. Imran has used him in every position from opener to number six, but with Aamir Sohail and Rameez Raja well cemented in the opening spots and with Javed Miandad and Salim Malik to support him in the middle order, Inzamam’s logical position is at number three.

He and the even younger Zahid Fazal, who had a disappointing World Cup but has done enough in international cricket to highlight his potential, will be crucial to Pakistan’s fortunes in the 1990s. ‘I just do what comes naturally,’ were the few translated words to emanate from Inzamam during the World Cup, and if he can just keep on playing naturally, the loss of Imran may not be quite so monumental. In 1992, Inzamam announced his arrival in England with 172* off 148 balls at Hove against Sussex, including 5 sixes and 13 fours.