Sir Frank Worrell had set his eyes on horizons beyond the cricket field. He came to Lancashire to earn his living as a professional in the League and to take his degree at Manchester University. He warmed to Lancashire (particularly Radcliffe, where he played), and Lancashire warmed to him. His twelve years there made him the most vibrant of Anglophiles, and so he remained. It was a Lancastrian, George Duckworth—that shrewd, humorous, lovable man—who, I think, first saw in Frank Worrell the special qualities of leadership.

It was a great honor for him when young Sir Frank Worrell was captaining a mixed Commonwealth team, primarily consisting of players much older than him, under Duckworth’s management in India at the young age of 26, ten years before he was recognized by his country for his achievements. At last, he was named captain of the West Indies on the tour to Australia in 1960. Although the appointment was accepted by the rest of his team, if not by him, as a challenge to his race,. Under the subtle knack of his personality difference of color, island prejudices seemed to melt away.

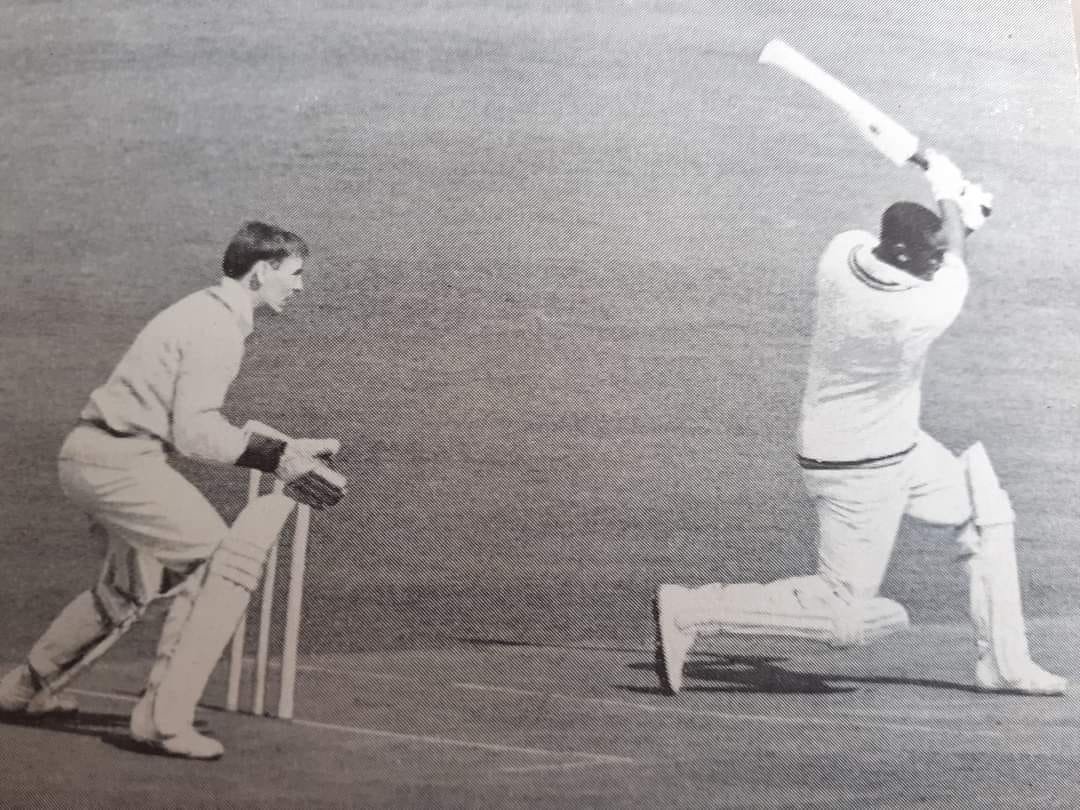

The tour of Australia was a triumph both on the field and off it, ending, as everyone will remember, with a motorcade through the streets of Melbourne lined with half a million cheering people. Three summers later, he brought the West Indies team to England for a tour that enthused the sporting world no less than the one in Australia. He retired from playing after this, and in the New Year of 1964, he received the honor of knighthood.

Sir Frank Worrell had a warm, understanding heart and a sort of sleepy charm that endeared old and young alike. In a time when international rivalries all too frequently turn nasty and vicious, he was essentially a sporting catalyst, bringing people together with his genuine and amiable demeanor.

Men who are well-known in the gaming industry have a strong effect in the era of television, and odd characters are occasionally elevated to the status of heroes. Frank Worrell was the absolute antithesis of the strident and the bumptious, of, so to speak, the great sportsman who is not. It is his example—and that of many of his West Indian cricket contemporaries—that has helped so much towards an appreciation and admiration for his countrymen in England and throughout the Commonwealth.

One of his opposing captains, in appreciation of him, wrote that however the game ended, ‘he made you feel a little better.’ Which isn’t a bad epitaph. No doubt he made many of us feel a little better, from the youngsters in Boys’ Town at Kingston to the Sydney hoboes on the Hill.

Read More: Frank Worrell on the tour of Australia in 1960–61