Inconsistent Umpiring: M. Wellings points a finger at some’ batsmen’s ‘pretend’ play. 15 years ago, a change was made to the LBW law, which complicated the job of the umpires while doing nothing to improve cricket. The change in 1970 allowed a batsman to be LBW even if the ball struck him outside the off stump, provided he did not attempt to play the ball.

It has, however, not proved difficult for batsmen, practicing a show of window dressing, to persuade the umpire in their favor. I watched the new law being flouted by a schoolboy in its first year during the representative school’s games at Lord’s. The young batsman was A. K. C. Jones from Solihull School, a player of obvious talent but one given to making the only pretense of playing at balls pitching outside but threatening the off stump.

He thrust his left leg well forward to block such balls and swung his bat outside its line. The umpires were apparently deceived by his strokes at an imaginary ball, for they passed them as genuine attempts to play the real ball while he was scoring 53 for the English Schools Cricket Association. Jones went on to join Warwickshire but did not make the grade in the first-class game, for all I know, because he thought too much of his pads and too little of his bat.

While writing about the school season in the 1971 edition of Wisden, I commented at length on this pad practice, which was contrary to the intention of the lawmakers. It also seemed that the umpires wrongly interpreted the new law, and they appear to be doing so today. This was evident during the second Test at Lord’s, where umpire David Evans seemed uncertain about the LBW law and was accordingly inconsistent.

He gave Graham Gooch out when he played a stroke against Craig McDermott with the clear intention of striking the ball, which came back from the off, beat his bat, and struck his left leg some inches outside the line of the stumps. Subsequently, Lawson, by contrast, was denied LBW decisions when the batsmen made no genuine attempt to play the ball outside the off-stump but headed for the stumps.

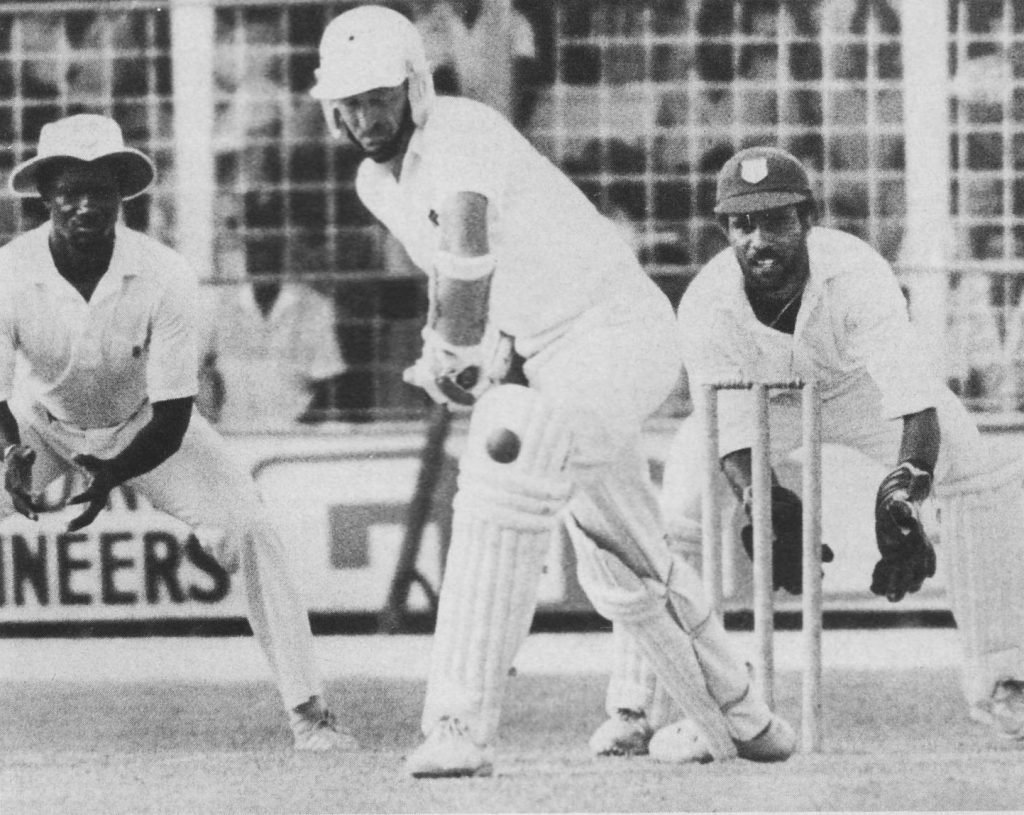

The method employed, a refinement of that used by Jones in 1970, was to thrust the left leg at the ball, with the bat following behind and protected from the ball by that leg. Lawson delivers from so wide, near the return crease, that balls going straight must pitch several inches outside the line of the wicket at a fast bowler’s length in order to hit the off stump.

At Lord’s, while McDermott was very lucky against Graham Gooch, Lawson was unlucky against others. Those against whom he appealed in vain were, in my view, quite blatantly merely making a pretense of attempting to play the ball. Short of blasting a hole through the batsman’s leg, there was no way in which the ball could get at the bat. That any umpire could have been deceived into thinking the batsmen’s attempts were genuine would have astonished me if I had not recalled the 1970 school match on the same ground.

After 15 years of the existing LBW law, are we to conclude that cricketing con-men can too easily dupe umpires? That would mean reverting to the previous law, which would be a damaging move, for the ugly left foot lunge with the bat held high in a Mike Gatting manner would be in general and frequent use. Before 1970, we saw much too much of that.

In particular, bowlers who thought that county captains Colin Cowdrey and Mike Smith were getting away with lbw murder agreed with them and found the excessive pad-play unedifying. Rather than revert to the old, much-abused law, it would be sensible to instruct and encourage umpires to make the existing one work properly. There are far too many examples in cricket history of administrators failing to encourage and assist umpires.

Here is surely a case for reversing the long-established maxim that the batsman should be given the benefit of the doubt in favor of the bowler. Not that there is really any room for doubt when the front leg is planted directly in the line of the ball. However, in the circumstances of today’s cricket, umpires should not be too harshly judged.

Doubtful of support and saddled with increasing responsibility during the post-war years, they have a fair excuse for errors. Perhaps the no-ball change from judging on the back foot to the front has been the worst umpiring imposition. It allows scant time for sighting the ball before it lands when the eyes first have to watch that foot and the batting crease. Here perhaps lies the explanation for the number of disputed decisions and the generally modest umpiring standard in the Test series.

One of those in dispute was Border’s dismissal of an alleged slip catch by Botham in the third Test. That he did not snick the ball onto his pad, from which it lobbed to short slip, I am convinced. The batsman’s actions were, for me, sure proof of that. Long ago, a doctor friend in Sydney drew my attention to the fact that, when a batsman edges the ball, he cannot avoid hurriedly and apprehensively jerking his head around to follow its course.

If that instinctive movement is missing, it is safe to conclude that he has not made contact. Allan Border was quite unconcerned about the ball’s destination. He did not look back until after the ‘catch’ had been made and an appeal shouted. When he did look back, it was as though he wondered what all the fuss was about. That was far removed from the action of a batsman whose dismissal is threatened.