Passion for the game—the cricket cult! The game is the new religion in the island nation, and its winning team is elevated to the status of a celebrity. But is it just a distraction, or can it bind a fractured country? There he was that Sunday morning. Half an hour out of Colombo, beside the paddy fields reflecting a cruel summer sun, under a patch of still palm trees, he played. It was absurd. He had no ball, no second person to play with, yet he—”My name is Asanke,” was all he said later—swung his bat and played alone with his shadow.

Content in his field of dreams is here too, away from the bustle of Colombo, in one corner of a forgotten land. Cricket had been embraced as the new religion. Something extraordinary has been unfolding in Sri Lanka. It is a land that has always had cricket. But once it was just a port; now it has become a national romance.

In this small nation of 18.5 million people, cricket is like a virus gone wild in the national bloodstream. In 17 months, they’ve won the World Cup, the Sharjah Singer Trophy, the Sri Lanka Singer Trophy, the Independence Cup, the Asia Cup, and set three world records in one Test. Now, suddenly, everyone has a story, and every field holds a promise.

The government, says an auto driver, hikes prices during the cricket season because no one notices. A gaggle of girls blushes as you interrupt their Sunday game because you are riveted by a pony-tailed pretender with a hook shot so fine the Indians may want to borrow it. Boys on the beach turn to grin at this stray visitor, then turn towards the bowler and become transformed into Conan the Barbarian with a bat.

They are not the only ones besotted: grandmothers argue LBW decisions and farmers, you are told, till the land with the radio calling out, “Sanath haye parak gahuwa (Sanath Jayasuriya hits a six)” and hanging underneath the tree. “Ah,” says cab driver Roger Periera, driving you in from the airport, “here, mothers give their babies bats before they give them the bottle.”

It brings a smile that exaggeration often does, yet the stories get still stranger. Rupavahini, the national television broadcaster, says that a staggering 90 percent of the nation’s 1.8 million TV sets were tuned into the World Cup final. But most wondrous of all is the tale Upali Dharamdasa, president of the Board of Control for Cricket in Sri Lanka (BCCSL), recounts.

Sitting in an air-conditioned office with the smile of a well-fed man, he says that on the day that Sanath Jayasuriya scored his 340, “there were 26 babies born that day who were named Sanath.” That is an irresistibly compelling story that housewives will talk about with great vigor. After all, sport here is not merely an Australian-style masculine disease.

As J.H. Wilson, sports director, Rupavahini, says, “My wife does her housework in time so that she can watch cricket.” But is it just a fractured country? Yet Sri Lanka and cricket are perhaps not just some silly romance. Its uniqueness lies deeper, making this cricket phenomenon more complex. In one sense, with the war not over and poverty not defeated, cricket has become a balm to soothe a wounded nation.

Two weeks ago, Sasanka Periera, professor of sociology at the University of Colombo, visited Buttala in the Sri Lankan south, an area once troubled by violence. A trauma clinic had been set up, but Periera found the streets deserted and the town ghostly. “Where is everyone?” he asked. Someone explained: “They are listening to the cricket.”

On that day, reality is banished, and people find a collective identity. The complete pride that cricket has bestowed is articulated in a single sentence by Dammika Ranatunga, chief executive of the BCCSL. He says of the night they won the World Cup, “I am privileged to have lived on a day like that.” It is difficult for an outsider to immediately understand what this Cup has meant to this nation and why this team has been cast as a sort of alternative pantheon of gods.

Most nations have reasons to preen; Sri Lanka did not have too many. Cricket-wise, they existed in the suburbs of the international game; 4 lands are good for funny stories like Sir Donald Bradman arriving there in 1948, only to find the pitch two yards from shore. But otherwise too, Periera contends: “This is a country defined in terms of mediocrity.” There are no great scholars, he says, no artists, and no serious heroes to display to the world.

Even soldiers, sometimes deified here, would, in a civil war scenario, appeal only to a particular section. This was a small country, says Nira Wickramasinghe, a history and political science professor, “that couldn’t compete.” Cricket is just a sport, so much so that the world has filled much of that with preaches. Heroes have been forged, each one infallible.

The hotel staff don’t blink twice When the Ferrari-driving Aravinda de Silva returns from the mid-second Test to the hotel at 1 a.m. Because they just know the next day he’s going to, and he does, for the sixth time in six consecutive Test innings at home, score a century. In the town’s hippest bookshop, Vijitha Yapa, posters of the Dream Team are sold out—500–600 last year, 300–400 this year—at a steep price of Rs 108. Says a beaming store manager, Rohan Wijesekara: “Before the World Cup, there were no posters.”

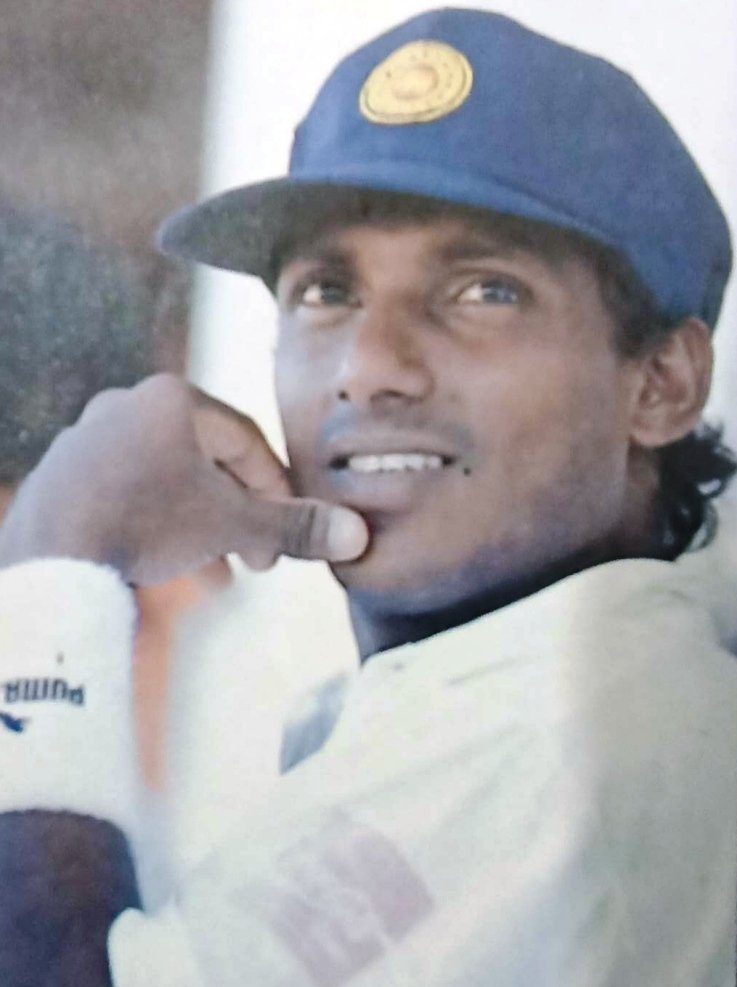

There is something different about these heroes, too. Once cricket in Sri Lanka was class-conscious and limited to the Colombo upper class, the team was almost entirely picked up from elite schools. That class system has been broken: smaller Buddhist schools produce stars; more importantly, nearly half of the team, including Sanath Jayasuriya, Muralitharan, Kaluwitharna, hail from towns outside Colombo.

Now they connect with every man. It has made cricket a democratic game; it has allowed for cricket conversations to move across classes. As Wickramasinghe says, It means in the market, the fruit seller and I can talk.” And, of course, her fruit seller has a story. Sanath Jayasuriya, the people’s hero, despite his celebrity, still drinks the same tea at the same roadside tea shop at his home in Matara.

But beyond the geographical confines of this island too, the walk is brisker, for cricket has become a way for this nation to market itself. Abroad, a Sri Lankan identity is beginning to emerge. “We were third-class citizens, and Sri Lanka had not much of a passport,” says Ana Punchihewa, former BCCSL president, “but now that’s changed.”

For all that, cricket cannot do everything. It cannot stop the war; its ability to heal a nation is possibly an overstatement. Even the self-confidence they possess now is fragile. Says Australian James Whight, who has begun the cricket club cafe in Colombo: “I fear this Pride, if they start losing, could be only fleeting. Cricket may just have come as a way of coping, but if so, it is believed that the narrow focus on cricket has obscured too many real issues that remain: I can’t tell my students anymore to study hard and you’ll do well.

I feel I have to say, Drop your books, play cricket, and you’ll be successful.” Some believe an achievement by a team is being confused with an achievement by a nation, and that a predominantly Sinhalese game cannot bind a fractured country. Nevertheless, it has reached a point, says former Test player Ranjan Madugalle, where politicians “use cricket to distract people from their problems.” Cricket has not become a metaphor for what is possible in other fields, either.

As Madugalle, who defines the Cup win as their greatest achievement in the past few centuries, says, “To achieve this with our limited resources should provide inspiration.” There is no evidence of that yet. Perhaps it will arrive eventually because this team’s nostrils continue to tingle with the smell of victory. One-day cricket is by definition considered unpredictable, but if it is a lottery, then Sri Lanka keeps buying the right tickets.

The statistics for 1997 stand as awesome proof: with their Asia Cup win, they have won 13 of 17 one-day games, making their winning percentage of 76.47 the world’s highest (India’s four wins out of 20 are the world’s worst). Yet, very subtly, this team is being confronted by a demon they never knew: pressure. Not just to retain their one-day status, but to achieve similar success as a Test nation—till 1992, they had lost 21 and won just 2 of 37 Tests. Yet, ask captain Arjuna Ranatunga and he says tartly, “Pressure, what’s that? I’ve been searching dictionaries, but I can’t find that word.” Yet he concedes that expectations will grow.

As a Test nation, Sri Lanka’s handicap has always been exposure: as of the second Test against India, 15 years since their debut in 1981–82, they have played only 76 Tests. In the same period, India played 116. As Dharadmasa explains, they were too poor to host nations and too mediocre for nations (worried about gate money and television revenue) to host them. Some of that has changed. As a touring team, they are now cricket’s version of the Harlem Globetrotters.

Their batting is like a fireworks factory caught fire, yet these adventurous Buddhists are cerebral warriors too. Six months ago, Sanath Jayasuriya hit the ball with the hurry of a man late for his wedding; this series, with 340 and 199, he displayed all the patience of a married man “We told him you have to realize the value of your talent.

Just look at Aravinda; we said, Look what he did for so many years.” They are also impeccably behaved in their smoldering stroke play, in almost paradoxical contrast to their affable manner. It has always been the case: 15 years ago, when they toured England and were asked about sledding, the assistant team manager replied disarmingly, “Sledging, what is sledding?” Financially, too, they breathe easier.

Now they have a Rs 19.8 crore television rights deal with WorldTel, a Rs 1.9 crore team sponsorship by Singer, school cricket sponsored by Coca-Cola, and players contracted for up to Rs 21 lakh a year. Unfortunately, though, their cricket too has been infected by ugly administrative bickering. Like India, their board is complete with honorary non-players in official positions, says Arjuna Ranatunga. “How can they make a decision?”

He is irritated too by the lack of development in the provinces: outstation players like Sanath Jayasuriya eventually follow the lure of employment to play in Colombo, but as Arjuna Ranatunga continues, “It would be better for cricket if he were playing for his southern province.” It is evident that the captain is about to make a powerful movement for change.

Till that happens, he has made it clear: “No administrators are allowed to interfere with my team.” In a way, it does not matter where this team goes, whether they fall back into mediocrity or continue to court success. They have not just made history; they have (superficially or not) transformed a nation to the point where a young Colombo boy tells his mother that when he dies, he wants to be buried with his cricket bat.

And they know they are the princes of the city. When asked during a conversation what his address is, the captain begins to explain, then stops, smiles, and says, “Well, I think if you just write ‘Arjuna Ranatunga, Sri Lanka’ it should be enough.” It probably will.

Reference: The article was published in The Cricket Magazine in 1998