Sachin Tendulkar Jewel in the Crown, a priceless diamond, sparkled, dazzled, and delighted. In nearly every field, new stars appear with breathtaking regularity, flashing across our skies and dazzling us for a time before suddenly disappearing and leaving us wondering if it had all been an illusion. So often, in our lust for new heroes, we see an acorn and imagine me as an oak already in full majesty, so that terrifying expectations are thrust upon immature talent. And if the acorn does not survive, a day of reckoning arrives as if the failure were his, not ours, for demanding too much too soon.

Meanwhile, old hacks churn it out—on time, under pressure, every time—and are neglected, taken for granted, even by themselves, amidst the cries of ‘ring out the old, ring in the new’. It has already happened to lots of young sportsmen and will happen again. How many new Bradmans have there been? So let us pause before announcing the dawning of a new age.

After all, between promise and achievement can be found a vast gulf; a day comes upon which every praised youngster realizes what a difficult game it is, upon which he understands his own mortality and his own fears and either learns to live with them or perishes. Nor should temperament quickly be judged, and temperament matters because, as Gary Player has said, ‘It’s not simply talent which sets champions apart; it is a compulsion to succeed and an obsession to pursue and perfect their skills as long as they can.’ Still, let us not prevaricate either, lest our youth be grey-bearded before any merit is acknowledged.

By any yardstick, any at all, the innings played by Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar, all of 18 years of life under his belt, in the Sydney Test match were outstanding. To see Sachin Tendulkar bat beside Ravi Shastri was to see a diamond beside a rock. Ravi Shastri batted for a trifling 572 minutes and promptly nearly bowled India to victory. In contrast, Tendulkar sparkled, dazzled, and delighted, and reduced his opponents to the role of admiring adversaries. He tossed the ball at twilight; he even took a wicket with an apparently negligible off-break.

Most great batsmen can play three shots especially well: the square cut, the drive straight of mid-on, and the tuck past square leg—bread and butter shots in England, chapattis on the subcontinent. Also, they keep their heads statuesquely still and do not miss their pads. Tendulkar produced all of these shots and lots of others besides, including a stroke off Merv Hughes which saw him rocking back to the leg stump and impishly gliding a straight delivery backward of the point at such a speed that the third man did not so much as try to intercept it. Edwardian mustache bristling, Hughes stood hands on hips, silent, wondering, respectful.

He did not curse—he could not curse such an enchanted moment. This shot was, of course, played late in the innings as India pressed for runs and Sachin Tendulkar cut loose. Otherwise, it was the power and timing of his drive that impressed most, the belted leather skimming across the outfield as smoothly as a puck across the ice. His judgment, too, was impeccable, with a staunch defense immediately following a devastating attack if the next delivery demanded it.

Sachin Tendulkar’s aggression was evidently calculated, and for a reason. Distraught at casting away his wicket in Melbourne to a wanton smite at Peter Taylor, he had vowed never to hit the ball in the air again on this tour. Such vows of abstinence are not uncommon amongst 18-year-olds, especially on Sunday mornings, and are more notable in their breach than in their observance. Nevertheless, this innings spoke of utter dedication and the confidence of a boy who, at 16, had been crestfallen at being omitted from India’s party to tour the Caribbean.

One more quality was evident in Tendulkar’s batting: he scores runs when he is not facing the bowler. It must be so. On one stage in Sydney, he scored 74. I chatted to a neighbor; Ravi Shastri faced a few deliveries, and I glanced at the awful new electronic scoreboard to find Tendulkar on 85. His batting is a rare blend of discipline, stealth, and panache.

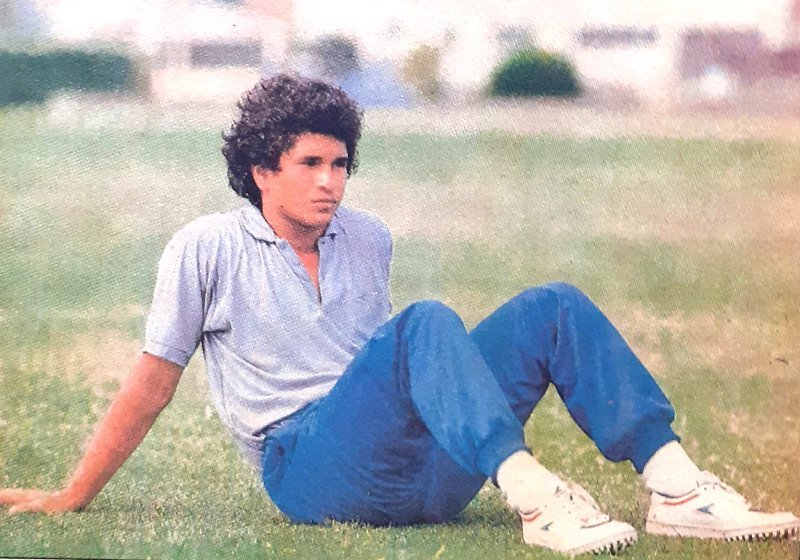

No innings of recent vintage have stirred the blood quite as much as this one. Sachin Tendulkar, the youngest of four children born to a college professor now retired, carries himself like an aristocrat yet has the passion of a competitor in his eye. He has it within him to be cricket’s most captivating batsman since the days of Vivian Richards, Sunil Gavaskar, and Gregory Chappell.