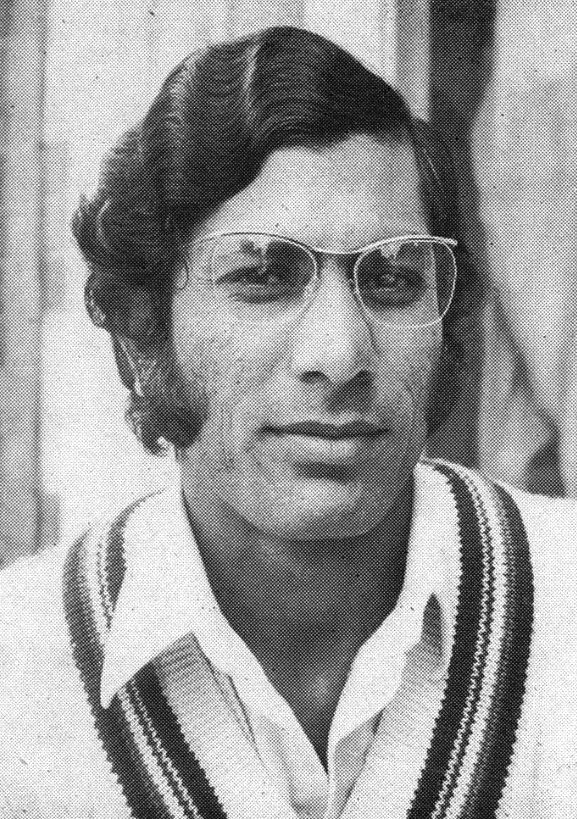

Zaheer Abbas’s flashback article from 1976. Well, it is patently wrong to call Zaheer Abbas a run-machine. The description implies super efficiency so well-oiled at the joints that success comes with unfailing predictability, devoid of mind and imagination. This isn’t his style at all. Zaheer Abbas is essentially a thinker, so intense at times when he is at the crease that it is etched almost painfully on his face. Cricket to him is an intellectual exercise.

The instinct is occasionally there — joyful and boyish — but for the most part, it’s kept in its place. Watching Zaheer Abbas this past summer has been a nostalgic experience. His sequence of innings has belonged to the ‘thirties when batsmen of timeless stature piled up the statistics and dominated the sports pages. We all know the names of the Gloucestershire giants who through the years brought style and consummate bat-ting skill to Bristol and Cheltenham, even the village greens of Frenchay and Cots-wold country.

Zaheer Abbas, handsomely in control for so many matches, looking at The Oval and Canterbury as though he would never be out, has assuredly 1976 stepped into their formidable company. He headed the national batting averages for much of the summer. He scored 11 Championship centuries, two of them doubles, and totaled 2554 runs, the most in an English season since 1961.

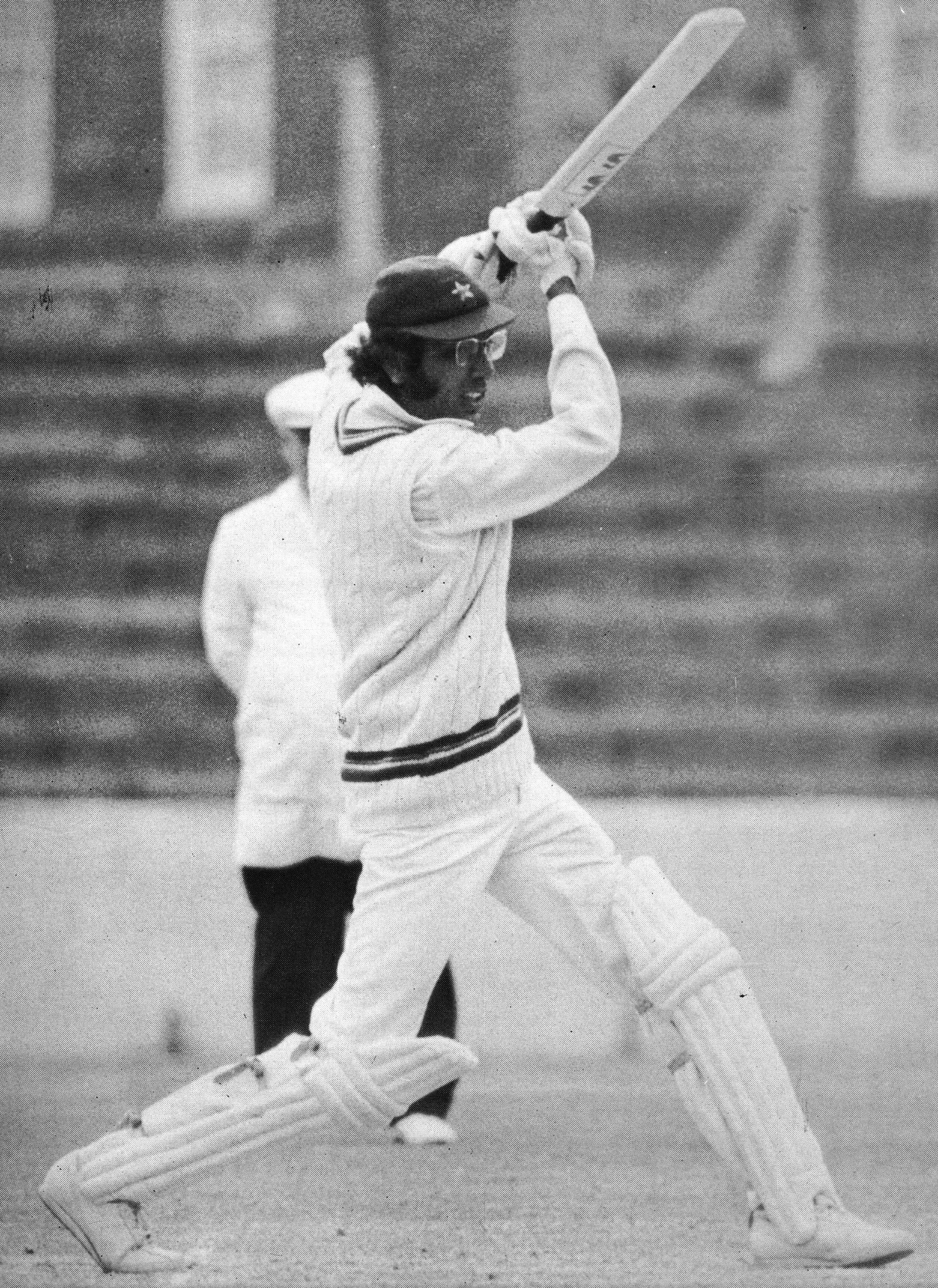

There were two more centuries in the Gillette Cup and one, his first, in the John Player League. He did it always with style, judicious in his choice of strokes, and seldom visibly fallible. After one of his irreproachably elegant innings, his captain Tony Brown called Zaheer Abbas one of the three great international batsmen of the day. Barry Richards and Viv Richards were the others. At the wicket, shirt neatly buttoned at the wrists and manner engagingly diffident, he has the trim, well-starched look of a choirboy. He surveys the approaching bowler with a challenging glint through his distinctive spectacles.

There is nothing ostentatious in the flourish of the bat apart from a mildly eccentric backlift which is fast receding, anyway. The shot, when it comes, is positive and calculated; it goes wide of extra cover instead of straight to him. He has been asked about his favorite stroke. `All of them, when they go where I intend,’ he says. He smiles readily, this quiet, courteous companion. Everyone calls him `Zed’; we watch him at work, diminishing the guile of a bowler, and we suspect that if the ability is any guide the alphabet is the wrong way round. He’s a cricketer the other players like; he’s strong on talent, refreshingly weak on bragging about it.

For a player who has looked so commanding so often this past season, it seems a slightly ridiculous commentary that he received no coaching at any time in his career. `No one else in my family played cricket. My father wasn’t very keen on my interest — he wanted me to study all the time. I’m glad to say he’s very much happier now! There was never any question of coaching for me. I picked up what I could from watching some of the best players in Pakistan and visiting teams.’ Zaheer Abbas is now 29. After promising form in provincial cricket, he played his first match for Pakistan in 1969; he joined Gloucestershire in 1972.

The first season in county cricket was limited and tentative: Zaheer Abbas had eight Championship games and scored 353. The following summer, in 22 Championship matches, he hit 1064. Frequently he appeared to be having difficulty adapting to our capricious wickets. There was little county cricket for him in 1974 — but 1426 Championship runs and two centuries in 1975. This has been his year. At The Oval he scored 216 in the first innings and 156 in the second; both times he was not out. Again at Canterbury, it would have needed more than a partisan prayer from the Arch-bishop to dismiss him.

He hit 230 and 104 and on his return to the West said rather sheepishly: ‘I only enjoy my cricket when I am getting runs.’ There must have been immense enjoyment for him in 1976. From his days with Karachi Whites, still, only just over a decade ago, he has displayed a flair for headline-catching feats. He first attracted attention in the provinces with three centuries in a row; in 1970-71 he did even better with four consecutive hundreds. In between, playing for PIA, he paid the penalty for hitting the ball twice. His opponents, Karachi Blues, were not in a benevolent mood that day.

The innings most of us will remember was his 274 for Pakistan against England at Edgbaston in 1971. Gloucestershire decided that there was the man to prop and inspire a shaky batting structure. ‘I decided I’d like to try my luck in county cricket and I told my colleague Sadiq Muhammad, who was already with Gloucestershire, of course.’ Nowadays he has a home on the outskirts of Bristol, where he lives with his very attractive wife and small daughter. In the winter he returns to Pakistan to help his brother in the family construction business, and to play what cricket he can.

Towards the end of the season, he admitted: `I have played too much cricket this year. When it is cold weather in England, I’m not bothered. But at the moment I am feeling very tired.’ He has reservations about 40-over cricket. `If I’m No. 3 and someone stays for 10 to 15 over’s, it gets very difficult for me. I have to slog.’ You sense the little shudder in his voice. He isn’t a slogger. His exquisite cover drive is made for the purist; the feet are right. You know he doesn’t approve of all this improvisation that has become an essential requirement of limited-overs cricket.

Zaheer Abbas is a tidy off-side fielder and has been known to bowl as a gentle off-spinner. It’s as a batsman, however, that he is a master: one for the record books of Pakistan and Gloucestershire, one for West Country fans to savor again in the memory as they reach old age. Significantly, Zaheer Abbas places Boycott technically well ahead of any other batsman in England; he also admires the more free-ranging style of Viv Richards and suggests that boys read cricket manuals too much.

Zaheer Abbas comes relatively late to first-class cricket, with parental pressures, and night school out of the way. He’s uncertain how long; now, he will stay before getting down to building houses in his homeland. He is a rare, studious, and always attractive talent, and Gloucester-shire can only hope that his self-effacing brilliance will be with them for a long time yet.