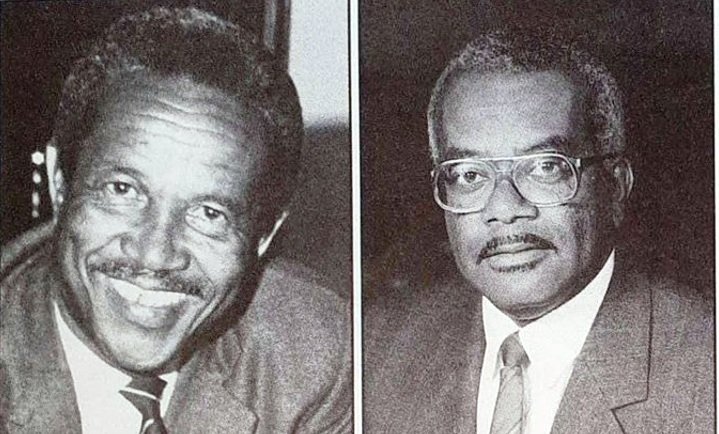

Trevor McDonald was a broadcaster and ITN News anchor named Newscaster of the Year. Trevor McDonald recounts his good fortune to have been known as a cricketer par excellence and a golfer. Years ago in Melbourne, I was having a round of golf with Sir Garry Sobers. His reputation as a devilishly good golfer had not been as widely known as it is now. Not to put too fine a point on it, he beat the hell out of me, so much so that I tried to switch the conversation, at least, to cricket.

We talked about playing spin, and I ventured, from the safety of the golf course, to suggest that I always used my feet to spin bowlers, and even before that, I tried to read their arms. Sir Garry Sobers went into fits of laughter. ‘You don’t need to read the bowler’s hand,’ he said. ‘OK, said I, ‘how do you play spin then?” The great man replied: ‘I watch where the ball pitches, see what it does and then I select my shot.’

I have frequently reflected on how accurately that response demonstrated the gulf between us lesser mortals and the truly stupendously masterful. Gary Sobers was all that and more. He did everything in the game maddeningly and brilliantly well. He could be a deceptively quick bowler; he could cut his speed to a genuine medium pace; as a slow left-arm bowler of the highest order, he could confuse the best players with his ‘chinaman. Gary was one of the most ferocious hitters on the cricket ball.

Sir Garry Sobers scored 28,315 runs in first-class cricket and 8,032 runs in Test matches, including his record-breaking 365 not out against Pakistan in Jamaica. He never neglected his defense, but he loved challenges. In 1968, he hit Glamorgan Malcolm Nash six sixes in an over, and three years later in Australia, he turned disastrous into a match-winning triumph by scoring 254 runs for the Rest of the World.

It was such a breathtaking inning that the great Don Bradman himself was moved to describe it as ‘one of the historic events of cricket’. And he could field against the Indians in Port of Spain in the 1960s. Sir Garry Sobers had arrived only a few hours before the fee had made a long journey from South Australia, where he had been engaged to play Sheffield Shield cricket. My fellow commentator, Sir Learie Constantine, had suggested that because of his long flight, it might be wise for West Indies captain Frank Worrell to keep Sobers away from the slips for a while, at least until he ‘found his feet.

Frank Worrell put Sobers at first slip. Wes Hall and Griffith charged into the bowl at the Indian opening batsmen. Some 20 minutes had gone by when the contractor tried to fend off a delivery that roared at him sharply. He managed to get his bat to it before it decapitated him, and the ball flew at speed, high to first slip. I can still see what happened next. Sobers climbed into the air, caught the ball cleanly with both hands, and came down to earth again. He was a demon in the field. Sobers is my favorite cricketer because he ran the game as he liked. No one could dictate to him.

Tom Graveney is fond of saying that he always knew what Sir Garry Sobers would do as captain, depending on how he’d done in the many departments of his game. Graveney told me that if Gary got no runs in an inning, he’d always want to open the bowling when the opposition batted. If he’d got a hundred, he’d wait to bowl, seam, or spin. He could do as he pleased.

Garry Sobers was a human. He was fallible. He occasionally misjudged things. In Port of Spain in 1968, he surrendered a Test match to Colin Cowdrey’s England team in a declaration that no modern cricketer would ever make.

He was unrepentant as they burned his effigies in downtown Port of Spain that night, and as England celebrated in the only English pub in the city, he said he was trying to inject some life and interest into a dying game.

In 1970, he took part in a single-wicket competition in Ian Smith’s Rhodesia, then a political pariah. His first sin was the reckless declaration that foolishly gambled with the pride of a cricket-mad nation, and his second was appallingly politically naive. But West Indians have learned to forgive genius, and Sir Garry Gary survived to thrill the wonderful world of cricket with memorable feats. What I liked about Sir Garry Sobers more than anything else was that he never lost sight of the fact that cricket is only a game. Gary felt, too, that it was a game to be enjoyed and to be played with honor.

He would have found it difficult to be a player today when batsmen touch the ball on its way through to the ‘keeper and stand there, pretending that nothing happened. ‘I always walk,’ he said, ‘because if you don’t when you know you’ve hit a ball, then that’s cheating.’

Tell that to the serried ranks of mediocrities today, and listen to all their gripes and bleating about how to balance those occasions when you get a raw deal from an umpire. It’s not really terribly wrong to stand your ground and leave the decision to the man in charge. Rubbish says Sir Gary, and so would I.

Sir Garry Sobers was never a great captain. How could he have been in the wake of Frank Worrell? I am persuaded that he never wanted the job anyway. He played the game with freedom and joy. He made friends and was a splendid ambassador for the game worthy of the best. He made mistakes and never really lived up to all that was expected of him in the Caribbean, but his playing left memories that will never be erased.

Last winter in the Caribbean, when the West Indies were playing Australia, I found Gary at the Kensington Oval, still pointing out the errors of his younger compatriots, still finding it difficult to understand that we are not all touched by the greatness that he was. We are not frequently given the chance to meet and know her heroes in life. I count it the pinnacle of good fortune that I have known Sir Garry Sobers, batsman, bowler, fielder, cricketer par excellence, and golfer.