The eccentricities of genius Mark Pougatch loved Alan Knott for his uniqueness. His hankie Headingley 1981 was a Test match that immortalized Ian Botham in the eyes of so many teenagers that he’s still their cricket hero a quarter of a century later. For lovers of English fast bowling, it was Bob Willis’s finest hour, and they argue his achievements are too easily overlooked. For one 13-year-old growing up in East Sussex, though, it was a match that reaffirmed that as good as Bob Taylor was with the gloves, his batting wasn’t up to it, and England had to bring their No. 1 wicketkeeper back into the side.

Alan Knott was England’s undisputed keeper between his Test debut in 1967 and the Packer affair that split the cricket world a decade later. In that time, he played in 89 of England’s 93 Tests, a testament to his durability, fitness, dedication, and all-around startling ability. Alan Knott, the cricketer, was, in many ways, a one-off. Whereas Taylor might have been the keeper easier on the eye and more orthodox.

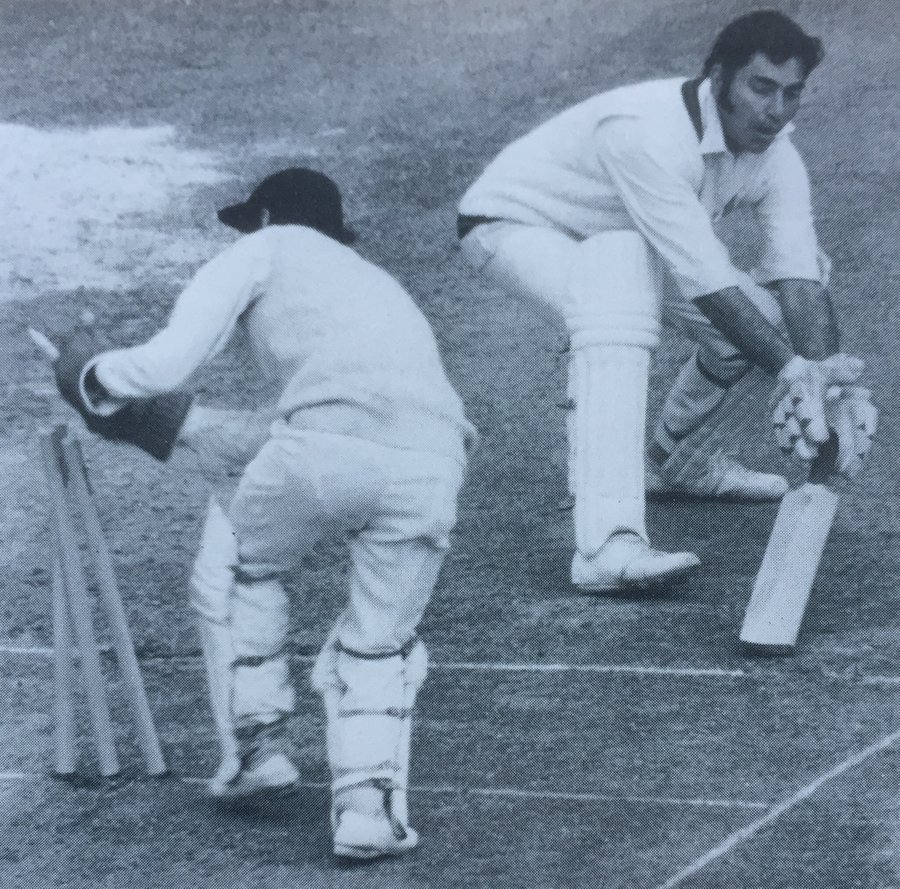

Alan Knott developed his own style, taking the ball on his knees when he could have stayed on his feet and catching the ball one-handed more than budding keepers are taught to do. His batting was even more idiosyncratic. He could sweep spinners to distraction, never minded chipping the ball over the infield, changed his grip when he thought it’s appropriate, and in 95 Tests, he averaged just under 33 with five centuries and 30 fifties.

His initials and APE were in keeping with his simian, craggy looks. It was Knott the Keeper who made such an impression on my young mind. My father was a madly keen cricketer, and although we lived in Sussex, he was a Kent member. He wanted to use a field in the village in which we lived for his wandering team called The Grannies, which this summer celebrates its 50th anniversary.

Dad wrote to both counties, asking for advice from the groundsman, but only Kent replied, so he became a member there. As I started playing cricket, it quickly became apparent that I couldn’t really bowl, so, being sporty and athletic, wicket-keeping became an obvious alternative. Thus, he would take me off to the St Lawrence grounds occasionally to watch Alan Knott keep to Derek Underwood, and with plenty of cricket on terrestrial TV, I could watch him whenever I wanted.

Knott fascinated me from the start. His initials, APE, were in keeping with his somewhat simian, craggy looks. He stretched constantly, even in the last hours of the day, and it always seemed to me that this was as much about keeping his mind active and boredom at bay as the limbs loose. Even today, I rarely keep wicket (when I do make it onto the field) without a long-sleeved shirt to protect my elbows, and there was even a time, when I was much younger, that I had a handkerchief peeping out of my pocket in homage to the great man. It was Knott who showed me that a fielding side takes its lead from the keeper and that he is their conductor.

This was reaffirmed for me when, at school, I was coached by one of those who just couldn’t dislodge him from the England side, the Leicestershire wicketkeeper Roger Tolchard. Watching Knotty, I realized that even if you didn’t make a run or take a catch, you could still play an enormous role in a team’s success, even if you couldn’t measure that through sheer hard facts. He was always on the move, always the metronome for the team’s fielding display. “The eccentricities of genius”, as Dickens called it, shouldn’t mask his ability He brought his own incredible run to an end by agreeing to join Tony Greig in Kerry Packer’s World Series experiment.

Not only did it offer him some longer-term security, but the short-term benefits were also evident too—a chance of a more stable family environment in Sydney rather than the nomadic life on the road in England. As a nine-year-old, I didn’t understand the politics and couldn’t work out why he’d voluntarily give up the chance to play for England, but by then I’d not only watched him, but on one memorable afternoon in Trentbridge Wells, he’d coached me too. All I can recall is diving across crash mats in a sports hall and him showing me how to turn my elbow as I landed so that the ball didn’t pop out.

If that was exciting, then some 14 years later I kept wicket to the man to whom he was umbilical linked at Kent, Derek Underwood. Playing for a team put together by The Cricketer magazine, I realized after a couple of balls that he really was medium-pace and that with his bounce, he’d be virtually unplayable on a drying pitch. He’d already had three players caught at the silly point when the No. 11 went to cut one and got a faint nick that my gloves somehow closed around. As we walked off, Underwood walked over to me and kindly said, “Alan Knott would have been proud of that catch.” I’m sure he was just being very polite, but I didn’t care.

I went straight home and told my father. Knott got back into the England team at the end of that Ashes series in 1981 and retired after making 70 not out in the last Test at the Oval. His ankle injury and increasing tiredness with touring were major contributing factors. He was certainly an individual, “the eccentricities of genius,” as Dickens called it, but that shouldn’t mask his enormous ability.

It’s worth remembering that he was replaced by Bob Taylor, at first only when he joined Packer’s circus and, secondly, when he retired. He was arguably the last of England’s great wicket-keeper-batsmen, as opposed to batsmen-wicket-keepers. In the current climate, when the quality of glove work is seemingly secondary to the ability to score runs, does the former exist anymore?