John Murray came to the MCC staff as a batsman in 1950, at the age of 15. He had learned the game at the Rugby Boys’ Club in Kensington. There were virtually no facilities at school, but the Boys’ Club, for whom his father had also played, had a good ground and gave him the opportunity for competitive cricket, football, and boxing.

John Thomas Murray (JT) was a footballer—he was offered terms by Brentford in 1952—and a boxer—he was the boys’ champion of Kensington. He decided early to concentrate entirely on cricket. He also started to keep wickets. As often happens, the beginning was fortuitous; the regular ‘keeper broke a finger during a game, and John stepped in. He made his debut for Middlesex in 1952.

From 1953 to 1955, he played for a strong RAF side. He took over from Leslie Compton at the end of 1955, won his cap the next year, and for 20 years has been an automatic choice for Middlesex. The rest of his career will be well-known to readers of The Cricketer. He went on all the major tours except to the West Indies and to Australia twice. He played 21 times for England; I was surprised it was not more. In my memory, he was as much the England wicketkeeper of the 1960s as Alan Knott is of the ’70s.

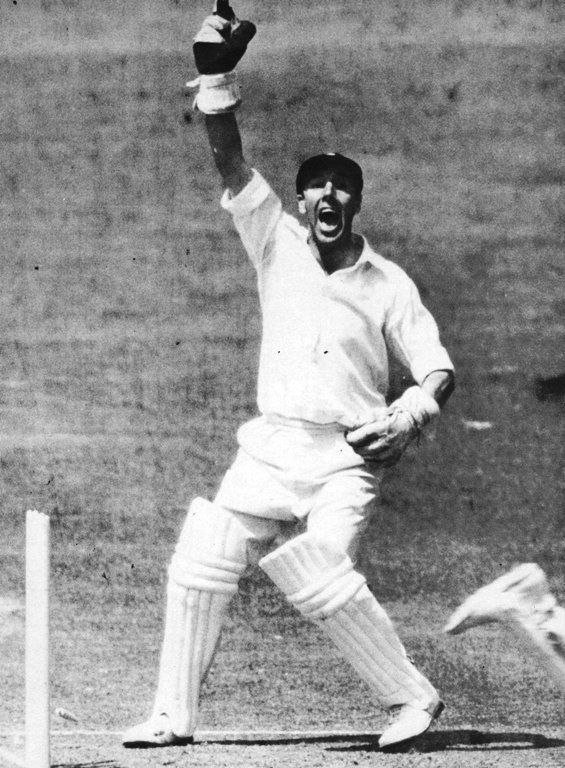

This summer, he broke the world record for wicket-keeping dismissals. One of the most striking features of JT’s cricket is the stylishness of everything he does. He is completely relaxed, whether taking the ball or stroking it wide off mid-on. His movements flow; when he is in form, he makes it all look so easy. He stresses the importance of rhythm and tolerance. Of all his contemporaries as ‘keepers, he most admires Wally Grout. ‘He was never on the ground except when diving for a catch.’ John’s mannerisms—the tips of the gloves touching together, the peak of the cap touching—help to give him that feeling of relaxed rhythm that comes across so characteristically.

I asked him if he ever doubted his ability. Yes, he said, he did, right up to 1961 and his first series for England. He had had, after all, very little wicket-keeping experience by the time he became a regular county player. He never worried about standing back. I think he regards the real test as one’s ability to stand up. We’d all agree, probably, but it’s worth remembering just how superlatively good JT was (he’d agree that a little of his ability is gone now) standing back. It is impossible to talk about his career without also talking about Fred Titmus.

Fred is not easy to keep wickets, either. For one thing, he bowls very straight; for another, he only really spins some of his deliveries; for a third, he has to be taken half the time at Lord’s, where the bounce of the ball has always been uneven. The extent to which they have helped each other is incalculable; perhaps the debt Fred owes John Murray is slightly greater since he so often can ‘feel’ what sort of pace Fred Timtus should bowl at, or what line, and so on. My clearest image of John’s ‘keeping is of the way he catches the ball. There could be no better model—fingers down, hands relaxed, and a long, easy ‘give’ to one side or other of the body. His batting has, overall, disappointed many.

He agrees that he has never concentrated on it and worked at it as he would have done if it had not been his second string. And it is unlikely that anyone could be both a front-line batsman and a wicketkeeper over a long period of county cricket without losing something of his zest for and concentration in the latter job. At his best, he’s a wonderful batsman.

He is often at his best against fast bowling (he’s a fine hooker and driver) and against slow bowling (he uses his feet and hits beautifully over the top). I think that it is characteristic of him that he should be least ‘turned on’ when playing against medium-pacers, where perhaps grafting would pay best. He is also a man for an occasion, an entertainer. He often saves his best performances for Yorkshire or Surrey and is less likely to sparkle on a damp Thursday at Ashby-de-la-Zouch.

I asked John Murray about his disappointments in cricket. He has, after all, achieved almost all that an ambitious young man could have hoped for. The one disappointment that he mentioned was that Middlesex has never yet won anything during his career. He thinks the best sides he played for were those of the late ’50s and early ’60s, though he admits that one tends to bring together in memory people who didn’t overlap. We have always, however, lacked one or two top-class bowlers to support Fred Titmus and, at different times, Warr, Moss, and Price.

Standards of cricket have declined overall, John believes. He is inclined to connect this with the gradual lessening of discipline in cricket and outside. I think that by `discipline’ he sometimes means hardship and knowing one’s place. When he came to the MCC staff, his place was clear and very low in the hierarchy. Lord’s was then, he says, a way of life.

He never resented the fact that he had to sweep the stands, that he had only one session a week reserved for net practice (they had to find time outside working hours for the rest of their practice), or that he was not allowed in the pavilion unless he was playing in the game. But the ambition was clearer and stronger; he could see exactly what he wanted to achieve and what he wanted to get away from.

Today, he thinks, it is perhaps too easy for young cricketers, and too many of them think they know too much. And, of course, you do need discipline to play this game well. He also believes in enjoying cricket. At a lunch earlier this season, John Murray said to the younger Middlesex players, ‘Play properly and enjoy yourselves’. He has done both for 25 years. First-class cricket will have lost a landmark when he retires at the end of this season.