India faltered badly, and the rubber is decided now, as India vs England 2nd Test at Lords, August 1967. India, who had shown enormous powers or recovery at Leeds, allied to a high degree of skill, were thoroughly outclassed at Lord’s in what almost amounted to only two and a half day’s cricket. Because half a day was lost on Friday due to rain, another half a day was lost on Saturday. But England’s victory by an innings and 124 runs came with half a day to spare on Monday. Once again, luck did not run India’s way, and things were moving the other way.

Subrata Guha failed a fitness test, and Duleep Sardesai was put out of the match (and the tour) when he sustained a broken finger, but this was only part of a sad story. The Indians may well claim that the way the pitch played on Monday was foreign to them. Against this theory is that they lost three key wickets before lunch, those of Farokh Engineer, Ajit Wadekar, and Borde, and not one of them could, in all conscience, blame the wicket for bad shots.

There was certainly some lift in the morning and a bit of turn, which increased after lunch, but nothing like enough for any bowler in the world to take five wickets for 12, as Illingworth did. He finished with 6 for 29. The story of the match, short as it is, concerns Murray’s six victims in the first innings to equal the Test wicket-keeping record held by Grout of Australia and Lindsay of South Africa; the superb innings of 151 by the elegant Tom Graveney; and Ken Barrington, failing so narrowly, to score his first Test hundred at Lord’s.

He was robbed by Chandrasekhar, who took five wickets, and the bowling honors, for India. The match provided next to no information for the England Selectors. They know all about Tom Graveney and Ken Barrington, and they must know, too, admirably, as Ray Illingworth bowled. Thus, it will be a different kettle of fish at Barbados against Sobers and Company. The one player who must have felt a little uneasy afterward was Edrich; he may be given just one more chance.

FIRST DAY

When India won the toss, they could have felt that luck, at long last, was beginning to favor them, but those who know (or think they know) the Lord’s wicket backward, were not quite so sure that India was capable, in these conditions, of weathering the first hour or so without losing one or two vital wickets.

In other words, winning the toss may well have been a mixed blessing. In fact, this is precisely how events turned out, and as early as twenty minutes to four, India was all out for 152. Only Ajit Wadekar had repeated the form he had shown at Leeds, with a graceful inning of 57. Duleep Sardesai was struck on the hand, and after retiring, did come back to bat with great courage, since it subsequently transpired that he had broken a finger.

But Engineer, Chandu Borde, Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, Rusi Surti, and Subramanya could manage only 19 runs between them, and the result of this was inevitable. D.J. Brown and J.A. Snow bowled well, but then so they should have done on a wicket, giving them a good deal of help early on, but the story was rather more a batting failure than a bowling success.

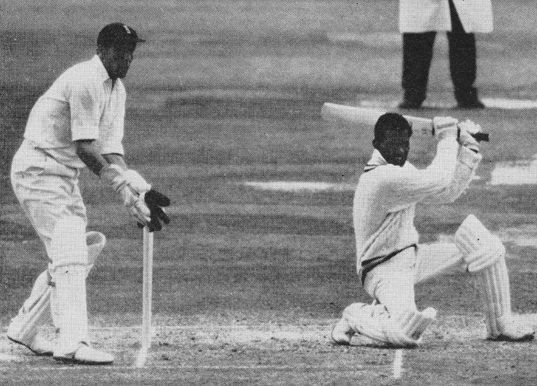

The real success, of course, was achieved by J.T Murray, who equaled the world wicket-keeping record in Test cricket by holding six catches, which Grout of Australia and Lindsay of South Africa had done before him. Murray appeared, in addition, to miss two other chances, the first before Engineer had scored.

The ball certainly struck a pad, but Close was heard to shout ‘Catch it’, so presumably it was a bat and pad catch by J.T Murray that did drop Rusi Surti, that looked like a clear-cut chance. How unusual for a wicketkeeper to have eight opportunities between half-past eleven and twenty minutes to four; another day he could keep vigil for six hours without a ghost of a chance coming his way. But full marks to Murray; he took his catches well and confounded his critics, who faulted him at Leeds. Perhaps he was just a bit off-color on that occasion. It was Murray who began India’s troubles when he caught Engineer (so even if he did miss him earlier, it cost very little), and then when Borde was bowled by Snow for a duck after Sardesai had retired, the gloom seemed to set in for the Indians. They never really recovered, bravely as Ajit Wadekar fought.

At ten minutes to four, John Edrich and Ken Barrington began the England innings, but Edrich was out for 12 and must have meditated anxiously upon his immediate Test future. It looked as though a miss would see the night out with Barrington, but he failed almost at the last hurdle (he was out in the last over) having made a useful 29. Barrington, with 54 to his credit, lived on to fight another day. At the close of the day, England was only 45 runs behind with eight wickets in hand.

SECOND DAY

After five uninterrupted days at Leeds, and on the first day here, the weather turned sour (by the law of averages, it was just about due to do so, judging by this present summer) just after three o’clock, and so cut the day’s play in half. In the three hours that were possible, England took their overnight score from 107-2 to 252-3.

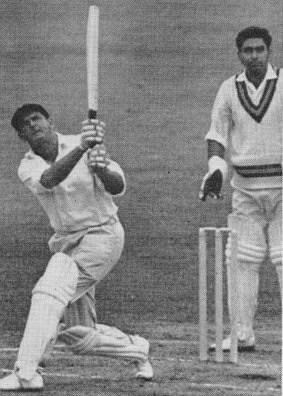

However, the wicket to fall was that of Ken Barrington, who, just as he had done at Leeds, got out in the nineties. This time he was only three short when he played outside a ball from Chandrasekhar and had his off-stump uprooted from its socket. For Ken Barrington, who has never made a hundred in a Test match at Lords, this was a great disappointment, because if ever a player seemed to have a hundred in his pocket, then this was it.

Ken Barrington, with abundant talent, and a player of immense experience, does have a tendency to become a little fidgety when he has a hundred in his sights, and perhaps, had he not been quite so cautious as the vital landmark was close at hand, he would have achieved an ambition. The crowd may well have seen a different Barrington, too, once he had gotten his 100.

This was probably a case of trying too hard and this comment is made without aiming to detract from Chandrasekhar, who got Barrington out. The upshot of the day’s play was that England had coasted to a lead of 100, with seven wickets still to fall, but most of all, for the Saturday crowd, Tom Graveney was 74 not out and had been playing beautifully.

Tom Graveney, in full bloom, has something to offer to the spectator that no other contemporary player has. He has a wide range of strokes at his command (now including the sweep), he plays with the fullest follow-through, which gives him the majesty of his own, and he will always put all his strokes on view, being prepared to take an element of risk. He is the artist; grafting remorselessly for runs is not in his pedigree. In the fifty-five minutes after lunch, he and Basil D’Oliveira added vital 60 runs.

Indeed, this was vintage Tom Graveney seemed to be one of life’s cruel twists of fate when the rains came and rang the curtain down on such entertainment as this. The Indian bowlers rarely ever looked like achieving a breakthrough. Bishan Singh Bedi, despite being clouted for six by Tom Graveney (a stroke which Bishan Singh Bedi generously acclaimed by clapping), did make one or two balls turn, but only slowly, except for one which whipped passed Barrington and caused him to shake his head. This was easy-going for the batsmen, as the wicket was now playing very well indeed. There was still likely to be a long haul ahead for India.

THIRDS DAY

Once again, as if the alarm clock had been left set at the same time as the earlier day, at Lords, play was washed again, with play being stopped for a day, a minute or two after three o’clock. Thus, once again only half a piece of cake is left for the customer’s money. But on the basis of quality being a richer virtue than quantity, there was full value for money. Tom Graveney took his overnight score of 74 to 151 superb innings.

There can be neither higher praise nor an inappropriate adjective more to the point than saying; just simply, this was Tom Graveney at his best. It is superfluous to say that a Rembrandt is well painted, so indeed, is it unnecessary to garnish fluent Graveney innings with details of its quality?

So much did he dominate the proceedings that he scored 77 out of 107 before lunch? Basil D’Oliveira managed only six in an hour, but although he did seem to be making heavy weather of it, he was allowing Tom Graveney the major share of the bowling. He was just a foil for the master performer and Tom Graveney was finally stumped.

It was a fitting dismissal, going down with all guns blazing in the attack. The rest of the England innings was a hotchpotch of not very much. Finally, wickets were thrown away (would a declaration not have been better?) and from passing 300 with only three wickets down, they were all out for 386.

Even so, this produced a lead of 234 and the odds were very much against India staging another remarkable fightback as they had done at Leeds. They were without Duleep Sardesai and were likely to be without the sun on their backs, for the rest of this day, at any rate. As it happened, the rain came before they embarked on the long road back.

FOURTH DAY

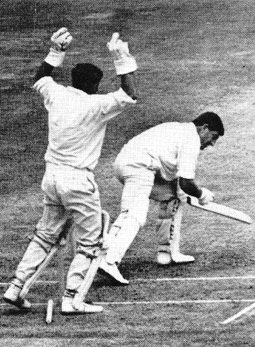

Torrential rain over the weekend gave rise to suspicion as to whether or not play would begin on time, but due entirely to the revised drainage system, there was no delay in getting the proceedings underway. The burning question was, of course, how will the wicket play? In fairness, to the wicket, however, it must be stressed that of the three Indian wickets that fell before lunch, those of Farokh Engineer, Ajit Wadekar, and Borde, not one was due to the caprices of the pitch; all three were poor strokes.

With Sardesai obviously not going to bat, this meant that the score at lunch was 75-4, and it was palpably clear, that if the weather lasted out-the Indians would not, but there was clearly no possible thought that the end would be so sudden and decisive.

During the morning, the wicket had certainly produced lift, and although there was some turn, it was not to any measurable degree. The way Illingworth exploited the conditions after lunch was the work of an experienced craftsman, but he will be the first to admit that he might be hard-pressed at times to bowl English players out in similar conditions.

The Indians seemed almost mesmerized, except, of course, Kunderan. If he could do so well, why did all his colleagues fail? The landslide started when the fourth wicket fell at 79 and this was Pataudi. The effect of losing their captain, who had inspired and led the magnificent fight back at Leeds, seemed to act as a death blow, and it was not long before the innings had perished altogether, as Illingworth spun a web of destruction.

At the same time, when the rain had concluded the day’s play on Friday and Saturday the game finished and there was a bit of waiting time pending the arrival of Her Majesty and the Duke of Edinburgh, to whom the teams were presented. The party then took tea together in the Committee room. Another match, and to all intents and purposes, another Series was over. The remaining match at Edgbaston could, at best, offer the Indians an opportunity to redeem their good name, which stood so proudly at Leeds but had faltered so badly here.