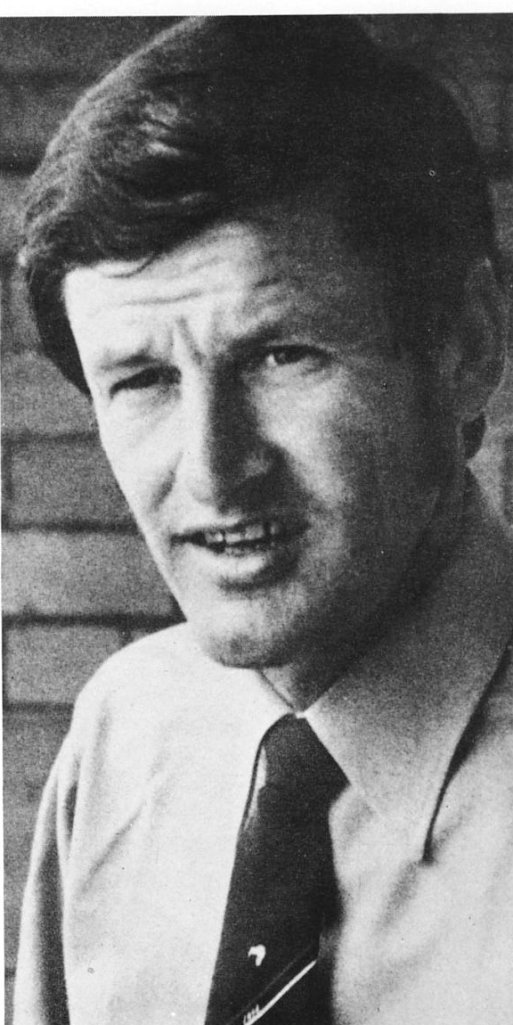

Bevan Congdon was one of the most influential cricket players of his generation. He was known for his graceful batting style and his ability to inspire others on the field. After a successful career playing for New Zealand, Congdon went on to coach the national team and help them achieve some of their most impressive victories. In this blog post, we will take a closer look at Bevan Congdon’s life and career and learn why he is considered such an important figure in cricket history.

Bevan Congdon was born in Christchurch, New Zealand, on February 11, 1938, at Motueka, Tasman. He started playing cricket at a young age and quickly developed a reputation as one of the country’s most promising players. In January 1965, he made his debut for the national team against Pakistan, and he went on to play for New Zealand until 1978. During his career, Congdon was known for his graceful batting style and his ability to score runs under pressure. He also played a key role in helping New Zealand win several important matches.

After retiring from playing cricket, Congdon went on to coach the national team. He helped New Zealand achieve some of its most impressive victories. He is considered one of the most influential cricket players of his generation, similar to Bert Sutcliffe, and his legacy continues to inspire players around the world.

There have been no more telling tributes to the works of C. S. Forester. Bevan Congdon was reading a Hornblower tale as New Zealand fought its memorable Trent Bridge battle against England. It may seem strange that a Test captain could read a book as his team, on the fifth morning, looked likely to achieve the impossible—a fourth-inning total of 479. All about him, his players reacted to mounting tension in predictable ways.

But Bevan Congdon sat there, reading. This ability to “switch off’ has helped to take a good cricketer into the ranks of the great. ‘Many captains are not good watchers in tight situations,’ said Congdon, in a dry, practical way, which has been a principal asset in newspaper, radio, and television interviews. ‘I read the book because I am a realist,’ he said. ‘Either we would win or we wouldn’t. A lot of worrying will not help your side play better. Tension does not help.

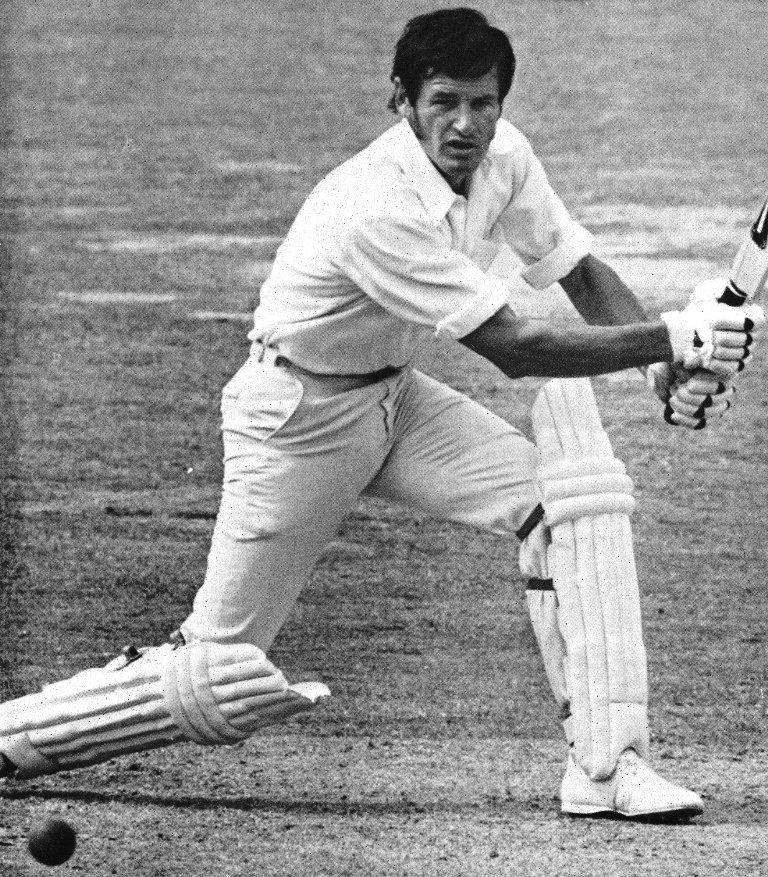

I base my game on keeping it as simple as I can and not allowing tension to come into it in any circumstances.’ Congdon has become singularly successful in the art of relaxation. Between deliveries in Test matches, he looks at advertisements, or he watches an aircraft fly by and studies the crowd—anything to keep him from thinking about the ball just bowled or the stroke just made. ‘If you forget about everything that has gone before, it lets you concentrate on what is coming,’ he said. ‘When I relax out there, it might give the impression that I am weary, but it is the way to rest.

I did not feel exhausted, or even tired, during the long innings at Trent Bridge and Lord’s. I pace myself fairly well.’ He needs to. In the Nottingham Test, he was run out for nine after batting for 40 minutes with aplomb and certainty, which was quite out of keeping with the desperate situation developing for his team. In the second innings, he was in for nearly seven hours for 176, as fine a fighting innings as any played in Test cricket. At Lord’s, he applied himself diligently to getting his side into a winning position, batting over eight and a half hours for 175.

For sheer determination, this lean, brown 35-year-old is almost in a class of his own. He is as fit and active as most players ten years his junior. But for all his practical ways and for all his successes, there is an appealing deference to him. Between his first Test series, in the New Zealand season of 1964-65, and New Zealand’s visit to the West Indies last year, Congdon was regularly but not spectacularly successful. He had made a modest start, and then, after 31 Test matches, he had scored 1559 runs at an average a little above 26.

In his five Tests in the West Indies and his next two overseas Test matches—Trent Bridge and Lord’s—he made 891 runs at a Bradmanesque average of 99. He was asked to account for the very considerable flood tide of his cricketing fortunes. ‘I think I learned quite a bit through batting for long periods with Glenn Turner,’ he replied. ‘I am probably adopting a slightly more professional approach now. I think perhaps my footwork has improved because I try to give myself as much time as I can, when the ball is in the air, before committing myself to a shot.

Before, I think, I tended to make an involuntary movement one way or the other. Now I try to see line and length before I commit myself and have a clearer decision to make.’ Bevan Congdon is the youngest of six brothers, all of them interested in cricket, but at 16, he almost gave cricket away in favor of tennis. He had enjoyed junior cricket in Motueka, a town in the northern part of the South Island.

Motueka is renowned in New Zealand for sunshine, fruit, hops, and tobacco growing. Now it is renowned for Congdon. He rejected tennis, although he had felt that being asked to play senior cricket at 16 would not bring the pleasure the game had given him earlier. He was 24 before he played first-class cricket. A country player in New Zealand has to be exceptionally good to attract much attention. But Bevan Congdon, in his twenties, found ambition burning within him.

He won a place in the Nelson Hawke Cup team—the New Zealand equivalent, broadly speaking, of the Minor Counties competition—had a good first season, and so was selected for Central Districts in the Plunket Shield contest. He has never looked back. Now he has more runs in New Zealand cricket than anyone who saves John Reid and Bert Sutcliffe. He has learned much—to discard, for instance, the sweep shot that cost him innings for a year or two; to bat out periods of good bowling so he can survive for another spell of batting plenty.

He is no Trumper, but Congdon today is an attractive batsman to watch. Patient, to be sure, but the strokes are there, and they are made when they are most likely to show a profit. At Lord’s, it was splendid to see his certain advance down the pitch to drive the slow bowlers. His contribution to the success of the New Zealand tour this summer is almost immeasurable. He has been an iron man, unbending in his defiance of England’s bowling. He very nearly led England’s little brother in Test cricket to two remarkable successes. He is a remarkable man.

Sometimes it seems, his world is limited by the extremities of the pitch and the man with the ball in his hand. This extraordinary application and skills, developed and matured over the years, have taken New Zealand cricket to a new height. And they have given Bevan Congdon a place all his own. In 1973, his finest moments came against England, when he scored a magnificent 176 at Trent Bridge and 175 at Lords in consecutive tests.

His 176 runs in 176 innings was the highest score by a captain in the fourth inning of a Test match, breaking Don Bradman’s 173* against England at Leeds in 1948. Later this record was broken by Michael Atherton (185* vs. South Africa at Johannesburg in 1995) and Babar Azam (196* vs. Australia at Karachi in 2022).

Related Reading: Bevan Congdon – How His Brother Forced Him Into Cricket