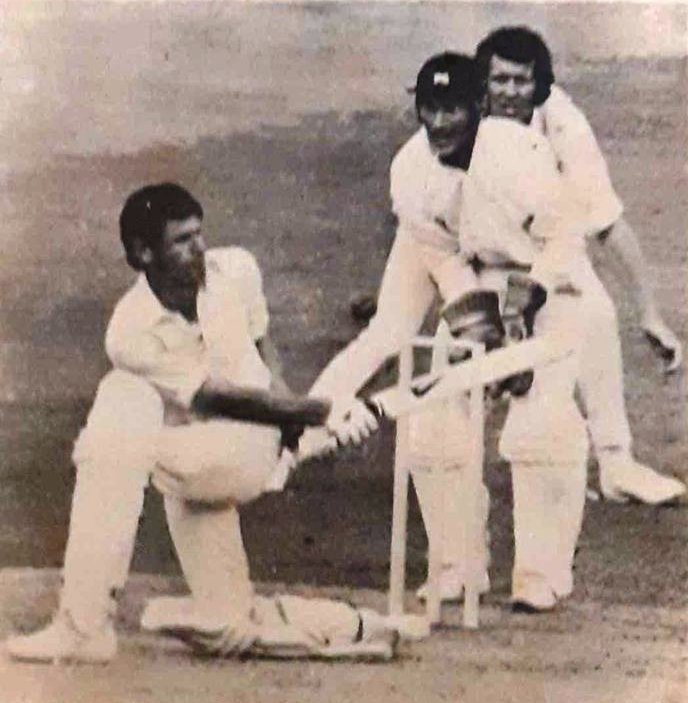

Bevan Congdon the 33-year-old New Zealand captain, has established himself as a world-class batsman. His tremendous batting and fine leadership were mainly responsible for pushing England to the brink of defeat in the two test matches.

When I talked to him, he expressed his disappointment in not clinching both tests, as one was drawn and the other lost by New Zealand. The Lord’s game was more so than the one at Trent Bridge because we were playing from strength, whereas at Nottingham we came from a long way behind. I cannot accept the criticism that I should have declared on a Saturday evening at Lord’s. Had done so, I would have considerably weakened the position we were in.

Bevan Congdon’s praise for Keith Fletcher’s innings at Lord’s was also generous, he played a truly great innings against us, damn it, he said, smiling. More importantly, it was an innings of great maturity and commonsense.

Bevan Congdon has one of his brothers to thank for talking up cricket. He was the sixth and youngest son of Cecil Congdon, who ran the local butcher’s shop in Motueka, a small township of nearly 3,000 inhabitants in South Island. When he was 16, he was invited to play in senior club cricket but turned down the offer because he felt he would not do himself justice.

I did not see myself as a cricketer. In fact, I fancied myself playing tennis after I had saved enough money. I bought a load of tennis equipment. When he got home, his elder brother looked at it and said, we will make a bonfire of that. You are going to be a cricketer.