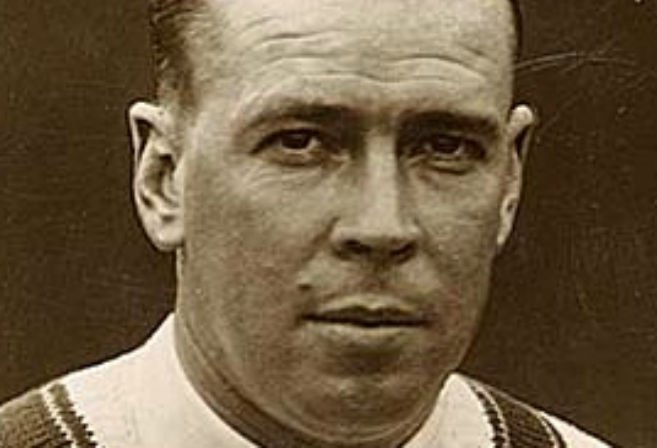

ANY cricketers have had their names blazoned on posters after the event, but Bill Ponsford of Victoria is probably the only one in the history of the game to have his name on posters before the event. It happened to him in Sydney early in January 1928 following the most remarkable month ever experienced by a cricketer in Australia. Nothing like it has happened since. Although I’m not especially keen on statistics, it seems desirable here to cite a few figures.

I think Bill Ponsford’s 1,146 runs in December 1927, made in five innings at an average of 229.20, represent the outstanding batting performance (in one month) of all time. His innings were 133, 437 (breaking his own world record of 429), 202, 38, and 316. These scores were the end of a string of 11 centuries in 11, consecutive matches in Australia. The others were 102 in 1925-26; 214 and 54, 151, 352, 108, 84, 12, and 110 in 1926-27; and 131 and 7 before the flood of runs surged in full force in that December of 1927.

It was all this that led to Bill Ponsford being postured. With a rare touch of business acumen, the New South Wales Cricket Association did something hitherto unknown to the game—it had big posters printed and tied to telegraph posts in the city and suburbs.

They hit Sydney in the eye “Ponsford,” they ran, “Come to the Cricket Ground and see the World’s Greatest Batsman.” The invitation was cordially accepted, the attendance being 67,614 over the days of play and the gate-takings £4,606. Both were records for a Shield game in Sydney.

But there the records ended. Bill Ponsford certainly didn’t contribute any. In fact, he made only six runs in the first innings and two in the second! As was sometimes his habit against fast bowlers, he shuffled across to the off against Jack Gregory, leaving his leg-stump open to be hit. Therefore in the second innings, Gregory again figured in his dismissal taking a typically sensational catch in the slips. Still, it wasn’t often that Bill Ponsford failed and this was one of the two worst first-class games he knew in Australia.

He had jumped into the headlines in the 1922-23 Australian season when he made 429 against Tasmania—not a Sheffield Shield state but enjoying the status of first-class games—and that tally eclipsed A. C. MacLaren’s 424, which had stood since 1895 as the world’s record first-class score.

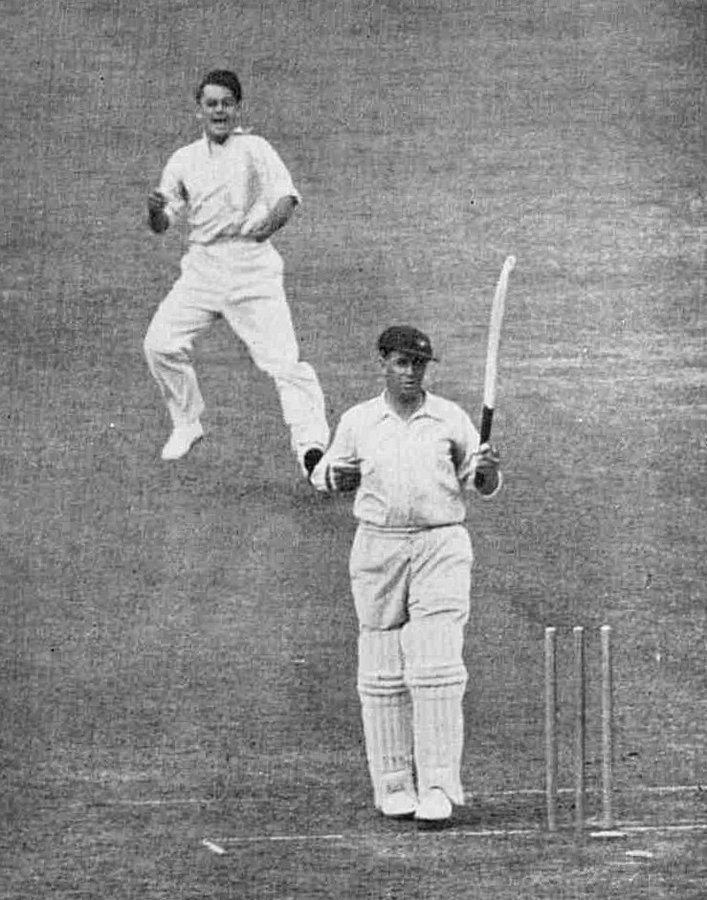

Five years later, again on his home ground of Melbourne, Bill Ponsford improved on his own record by making 437, this time against Queensland and in a Sheffield Shield match. However, Don Bradman was now on the horizon and Ponsford’s record endured for only two years when Bradman toppled it (also against Queensland) with 452 not out in Sydney.

Bowled by Selectors!

That score of 452 not out remains the world’s record. But not even Bradman equaled Ponsford’s feat of making two first-class scores of over 400. Aptly, in a sense, Pension’ retired from cricket after the 1934 tour of England, during which he teamed with Bradman to put on 451 in the Oval Test (Bill Ponsford 266, and Don Bradman 244) and 388 at Leeds (Ponsford 181, Bradman 304).

These partnerships in order were for the second and fourth wickets and are record ones in the Australia-England series. They were the only occasions on which Australia’s great record-breakers got together in a Test as a “firm,” although this was something that had been eagerly awaited since Bradman shot into the records’ list in the late 1920s.

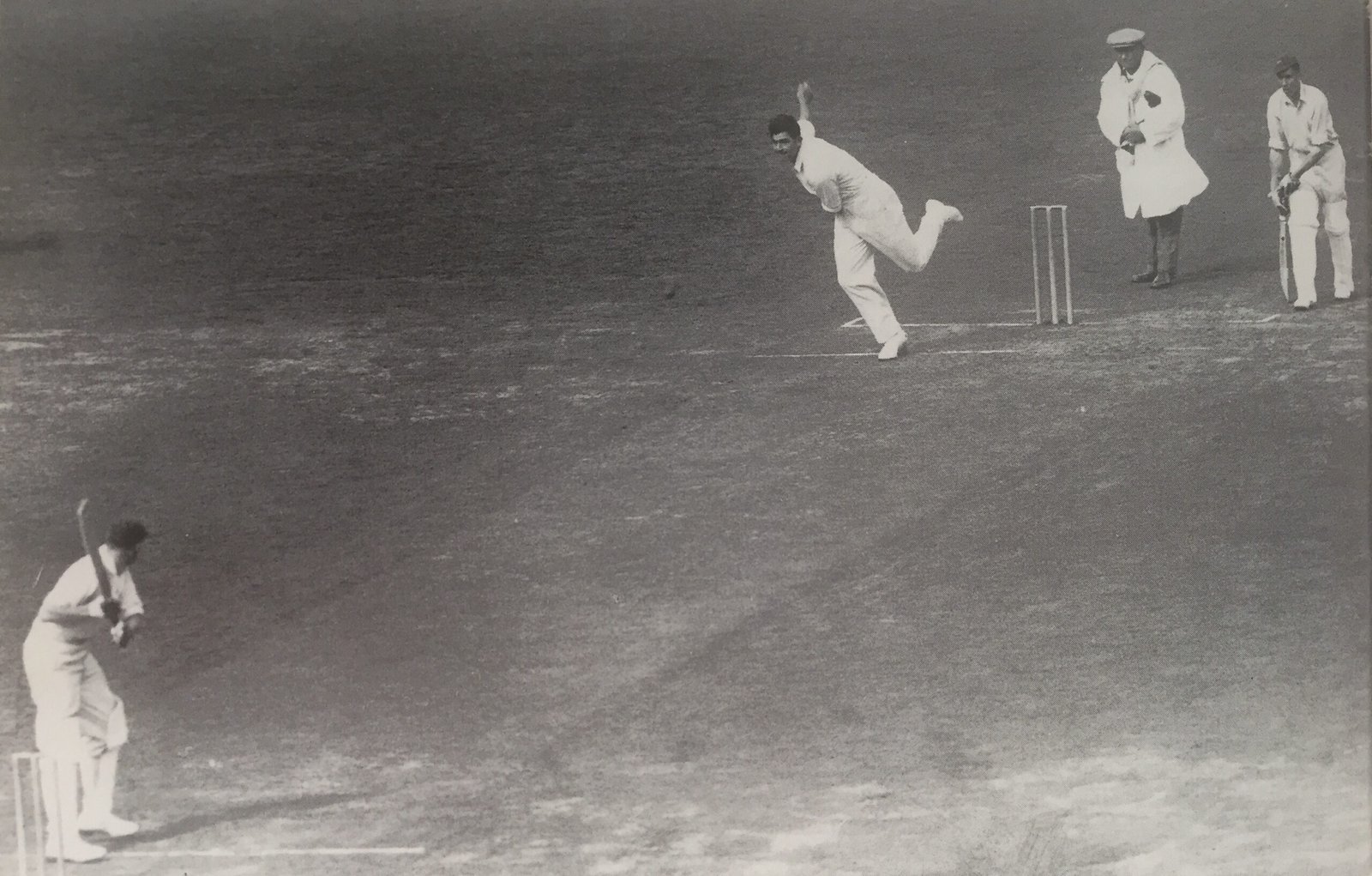

As was to be the case with Don Bradman later, Bill Ponsford had his wings clipped by Harold Larwood. The speedy Englishman scattered his stumps for two in the first innings of the First Test at Brisbane in 1928 and had him caught behind the wicket for six in the second innings.

In the first innings of the next Test, in Sydney, he had made only five when a ball from Larwood fractured a bone in his hand. Bill Ponsford played no more in that Test series. He was left to lament some “famous last words” that appeared under his name at the beginning of that season in a Melbourne newspaper, “Larwood,” he had said,” is not really a fast bowler!”

Bill Ponsford came back to make his favorite Test score of 110 at the Oval in 1930. But Larwood loomed up again in the next series in Australia—the bodyline period. Larwood clean-bowled him for 32 in the First Test at Sydney and Voce clean-bowled for two in the second inning. As a remarkable fact, Ponsford was dropped for the next Test, appearing on the field in the incongruous role of a drink waiter.

But he played a very plucky inning of 85 in the following Test at Adelaide—that match of extreme bitterness —and then was shot out for three, by Larwood, in the second innings. Larwood bowled him for 19 at Brisbane and caught him for nil off Allen in the second innings.

That was the end of Ponsford’s Test career in Australia—the selectors clean-bowled him before the final Test began. Obviously, Larwood gave Ponsford much anxiety, and there was certainly substance in the claim that fast bowlers the beat of them, that is—sometimes found a chink in his armor, or, to be more precise, caused a flutter in his temperament and a stutter in his footwork. That was something no slow bowler ever did.

Indeed, it can fairly said that from 1921 onward cricket knew no greater batsman than Ponsford against slow bowling. Bill O’Reilly once told me he would sooner bowl against Bradman than against Ponsford. He gave himself some chance of breaking through Bradman’s defense—sound as it undoubtedly was—but the job against Bill Ponsford always struck him as being virtually hopeless.

Like most famous Australian Players, Bill Ponsford came into cricket at an early age. He was a few days short of 16 when he played his first game, for St, Kilda, in Melbourne pennant cricket. He quickly made an impression with sound defense, composed temperament, and a marked keenness for the game ‘Yet, strangely in the case of one who was to make mammoth scores, the century eluded him time and again in the pennant games.

He was a good scorer, ranging from the 60s on to (once) a tally of 99; but he still had not made a pennant century when he was chosen, at the age of 20, to play against Johnnie Douglas’ M.C.C team of 1920-21. He wasn’t a success, he made only six and 19, and, as the cricket selectors of Victoria have usually been conservative—those in New South Wales have often been just the opposite—he was relegated to pennant cricket again.

Hardest-earned Century

In the season of 1921-22 he gave the Tasmanians a slight taste of what was ahead, making 162, and in the next season came that record 429 against them. Ponsford’s name immediately became big news. He moved up into the Victorian Shield team again, this time to stay until he himself cried “Enough” in 1934.

He played his first Shield game against South Australia and made 108 and 17. He played his first Test against England in the next season, and, as in the Shield game, began with a century. He says to this day it was the hardest-earned century of his career.

“I was 24, and a very nervous young man”, says Ponsford of this match. “I can never seem to remember with any accuracy much about cricket dates and statistics. But that day on the Sydney Cricket Ground, December 18, 1924, although nearly 33 years behind me is fresh as today and much more memorable.

“Maurice Tate Was a big-shouldered, 16-stone giant, with a deceptively short run. He came in flat-footed and swing his arm over. He was extremely expressive and I thought I saw the ball well. I went to make my stroke, and the ball swung a little, hit the pitch, and fizzed through like a flat pebble off a mill pond. It beat me, beat the wicket, and beat the ‘keeper, Bert Strudwick. It went for four byes runs.

“The next ball, I swore, would not do the same humiliating thing, although this time Strudwick took it. I the third ball I watched as if it were a bomb. But again it swung at the last moment, came off the pitch Like a Larwood bouncer, went through me and the wicketkeeper as well, and shot to the fence for four more byes, Little “Tich” Freeman was bowling leg-breaks at the other end. I got a four off him and was so relieved at missing a “blob” that my, confidence, so shattered by Tate, returned, I made a century, which I think was chanceless, and we won the match, on the seventh day, by 198 runs.”

Thus Ponsford told his story many years afterward, But he emitted some important details, At the other end was Herbie Collins, the Australian Eleven skipper. Those who saw Ponsford make his shaky start against Tate (the sheen had gone from the ball, Ponsford coming to the first wicket down with the score at 40), will never forget how Collins strolled up to him at the end of the over, had a talk, and then kept Tate’s bowling exclusively to himself until the younger man had recovered his poise.

This so was a classical example of how one man can make a century for another. If he has the ability, the intelligence to work on the strike, and the team spirit to protect somebody in trouble. Maurice Tate, that day, almost shed tears of frustration because Collins wouldn’t let him “get a Bill Ponsford. Therefore Bill Ponsford made a super 110 in his first Test innings against England; Collins made 114.

The former Australian Eleven skipper (one of the most modest of men) prefers that it should not record the details of the conversation he had with Bill Ponsford a the end of that nightmare. Over but he emphasized that he will always remember. Posford’s gesture when he returned to the dressing room after making his first century. The team naturally much fuss over Ponsford.

He postponed much of the slaps on the back and the handshake and went across to Collins to take his hand. This chap said Bill Ponsford deserves most of the credit. Writing of Larwood recalls my own first Test innings against England also in Sydney. I should have got off my blob first ball by placing a single from Larwood but when halfway up the pitch I saw my partner at the other end with his hand up countermanding my call I turned scrambled and finally dived narrowly escaping being run out. One or two of our men in that series were not at all eager to get down to Larwood’s business end.

Bill Ponsford made another century in his first Test series of 1924-25. He made 126 in the second Test at Melbourne and he finished the five games with the splendid figures of 468 runs at 46.86, nevertheless, he never scored a test century in Australia against England like many others. He was eclipsed by Don Bradman’s big scoring in the Test in England in 1930. Bill Ponsford made 330 test runs at 55 innings and Bradman scored 974 runs at 130 averages.

“Big Bertha”

On figures, however, Ponsford finished his career in England in a blaze of glory. Whereas on his first trip to England in 1926 he just made 37 runs in three Test innings. However on his final tour, he made 560 runs at an average of 94.83; and in so doing he shaded even Bradman, Whose figures were 758 at 94.76. But—and this is an important point in relation to both Bill Ponsford and Bradman.

There was no Larwood and no Voce in 1934. Both were steed down by Marylebone in the aftermath of bodyline. Whichever way you look at the Bill Ponsford records—at his figures or when he was in the midst of big scores he was a truly great player.

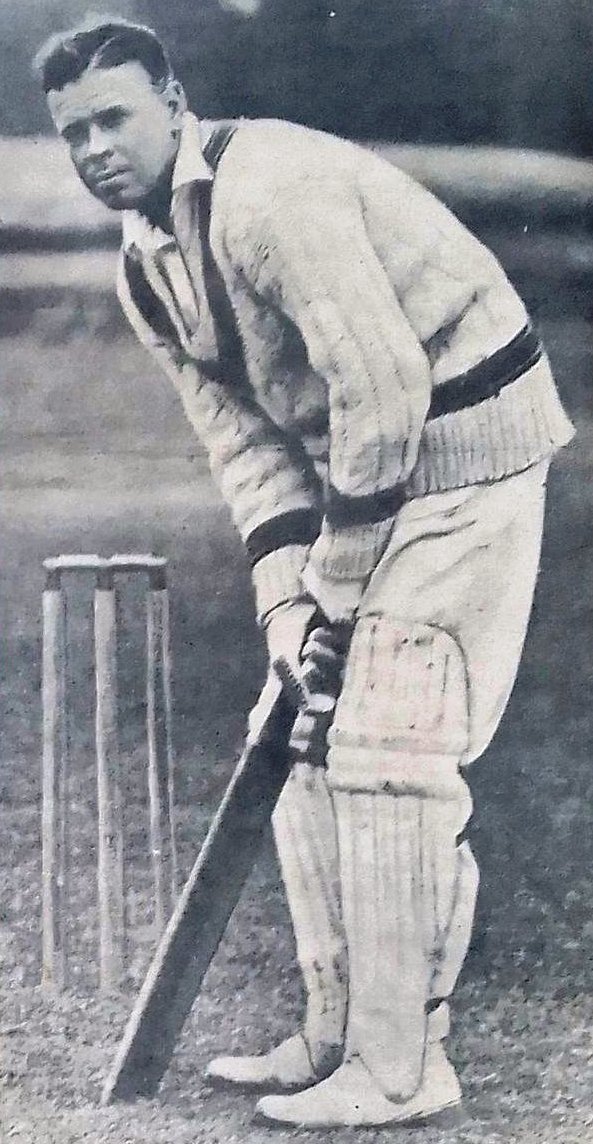

He crouched a little at the crease, the peak of his cap pulled characteristically towards his left ear; he tapped the ground impatiently with his bat while awaiting the ball, and his feet were so eager to be on the move that they fan an impulsive move forward just before the ball was bowled.

Read More – Ernie Toshack – Member of Bradman’s Invincible Side