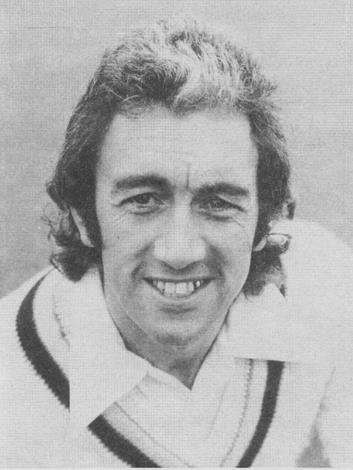

Artistry and the name of Bob Taylor have gone inextricably hand in hand for so long that there could scarcely have been a cricket enthusiast in the country who did not quietly nod approval when he departed for Pakistan in November as England’s undisputed No. 1 wicketkeeper. Justice had at last been done. After only one Test appearance in more than a decade of quiet, almost introspective consistency—and that was awarded as something of a placebo on a Christchurch pitch that proved no friend of wicketkeepers—Taylor’s private frustrations had at last disappeared, although it took Kerry Packer and his oligarchy to do it. Alan Knott, who is Taylor’s close friend, once told me that he felt he would never have gotten into the England side if Bob Taylor had been first on the scene.

In a recent newspaper piece, I gather, he went even further and said his rival was the better all-round wicketkeeper. All of this, without diminishing Knott’s contributions to the game, has long been felt by the typical county professional, a man who can be counted on to make sound, often deep, unwavering decisions. Plaudits have been heaped upon Bob Taylor almost from the day he first stepped onto the Derbyshire side in 1961. He is, incidentally, only the county’s third post-war wicketkeeper, after Harry Elliott and George Dawkes.

He is also county cricket’s Mr. Regular Nice Guy. No one has a derogatory word to say about him, on or off the field. Most people speak almost reverently about his ability, which has been refined to a high level of perfection via discipline, dedication, self-analysis, and hard work. Yet you are occasionally permitted a fleeting glimpse of another Robert William Taylor after many years as a friend of the man. Sometimes, inevitably, he does betray a hint of frustration and depression, whether because of his performances or because of a lack of pride and professionalism by someone playing alongside him.

His tenure as captain of Derbyshire, I know, stretched his equable temperament, though as a player, his consistency shone like a beacon through those dark, depressing seasons earlier in the’seventies. On his handful of tours, he has cheerfully accepted a role that he knew carried no more glory than that of bellhop: carry the drinks, mind the kit, fetch the mail, endless fielding practice. He was never found wanting, especially when Alan Knott himself sought assistance, but one night in New Zealand, Bob Taylor just couldn’t hide his feelings. We had just left a reception, one of those functions where you wear your name on your lapel and must abandon yourself to relentless questioning from blue-rinsed matrons who cannot distinguish a cricket ball from an orange.

One of them, eyeing the neatly-printed ‘R. W. Taylor’ on Bob’s immaculate (of course) jacket, queried: ‘And who might you be?’ A harmless, ice-breaking question, you might think, but it struck at the heart of the man who had been living in the shadow of Knott for some four months on a tour that was a great strain on all concerned. Who might you be? Suddenly, you could understand why Bob Taylor has sometimes talked of no more touring, though happily, the love of the game and the lure of foreign parts have always prevailed, if not the judgment of the selectors. Taylor is one of many talented players who make Staffordshire folk think they could have held their own in the championship.

Unlike Arnold Bennett, who never came back, Bob Taylor has never really left. His house ‘Hambledon’ (and, yes, there is one Derbyshire player who does not know why it is thus named) is on the fringe of the Potteries, just a mad car dash, Bob Taylor-style, from most Derbyshire grounds. It wouldn’t be surprising to see him drift back to league cricket when he decides his standards are no longer high enough for the first-class game. Cliff Gladwin first noticed him while he was playing for Bignall End.

The raw, ingenuous Bob Taylor of those days contrasts vividly with the dapper, sharply-dressed man-about-cricket of today. In his first match, struggling to the middle in black plimsolls, grey trousers, and chest-high pads, he was asked: ‘Are you wearing a box, lad?’ He had to admit he did not even know what a ‘box’ was! Today, Taylor is a lovely mixture of sophistication and modesty.

He learned early on the wisdom of dedication, missing the first seven matches of the 1964 season with a football injury; he told Derbyshire he had slipped on an escalator while shopping with his wife. That little episode nearly changed his career. Laurie Johnson, who replaced him, did so well that Derbyshire, short of runs as usual, was tempted to continue the experiment and play the extra batsman. Fortunately, the club realized the folly of their thinking, and Bob Taylor was re-instated, his only other lengthy absence came three years later, when he edged a ball from Jack Birkenshaw into his eye and was out for three weeks with a detached retina.

In his first full season, 1962, Bob Taylor broke Derbyshire’s wicketkeeping record with 77 catches. Other statistics—ten dismissals in a match, all caught—and seven in an innings twice, the only man in history to achieve this feat more than once-set out the value of Taylor’s achievements in cold figures, but it is possible that his wicketkeeping will be remembered equally for its aesthetic qualities. In Derbyshire, people pop into a match at lunchtime to watch Taylor ‘keep’ as they do elsewhere to see someone bat or bowl.

Elegance, whether making a difficult leg-side take for a spinner or launching himself in front of first or second slip, is the quality that springs to mind. He is now proficient in standing up to spin or medium-pace, but this was not always the case. In his early days, the lack of spin in the side hampered his development and when he tried standing up to bowlers like Derek Morgan and Ian Buxton, there was invariably an exchange of words when nicks he would have swallowed standing back went astray.

He once dropped Roy Fredericks three times in quick succession, standing up to Buxton, though perhaps only he would have classified them as chances. By the same token, he has missed so little standing back that Alan Ward once checked with an opposing batsman that he really had gotten a touch before accepting that Taylor had actually dropped a catch off him! Typically, Bob Taylor discusses his art only in terms of standing up. He gets as close to the stumps as possible, though this increases the margin of error.

When he gave up the Derbyshire captaincy, one reason was that it was affecting his form, though it was almost impossible to detect. Bob Taylor is his severest critic, though, and the press-box spectator can often tell whether a chance has escaped by watching to see if his head goes down for a few moments before the next delivery. ‘If I am keeping badly,’ he once told me, ‘It is usually because of one of three reasons, lack of concentration, standing up too soon, or snatching at the ball. The longer you stay down, even for a thousandth of a second, may mean the difference between the ball glancing off your fingertips or sticking in the middle of your glove. I am a professional; others rely on me, and as far as I am concerned, it is a crime to let them down.’