On that wintry, British-bleak morning, the family made its traditional huff-puff, mittened, foot-stamping pre-lunch walk down to the fire station and up and over the Stoke D’Abernon recreation ground. A romantic could warm himself in the mist of that silence, and, sure enough, what’s this? Yes, I really hear it—a ghost with gusto, a ghost bounding across the frost-hard field, a clatter of size 12s, a flail of arms and knees, an enthusiast’s grunting. For this was the patch, the Stoke D’Abernon ‘Rec’, where Bob Willis played out his childhood games: ‘You be Statham and I’ll be Trueman’.

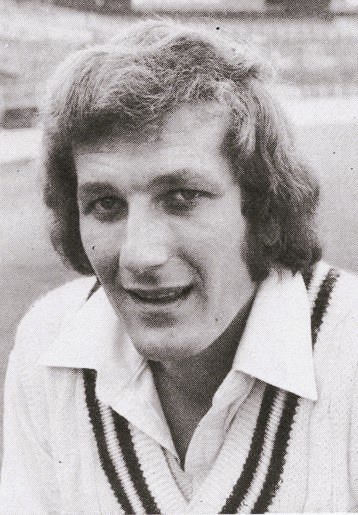

The boy then had a run-up as steamily furious as the Royal Scot’s Glasgow run—and nearly as far. He was already a long lank of angle, all knees and legs, red-faced and short-haired. Now, a dozen or so years on, still bright-eyed but now bushy-haired, Bob Willis was a million miles away. Now he was England’s prime shock bowler. Christmas Day was just a few days after the astonishing first Test match against India at Delhi. Bob Willis had been picked in spite of being bedridden with a chesty cold for much of the MCC’s first fortnight.

The selectors insisted he played for his ability to rattle the breastbones of the diminutive Indian batsmen, to shiver the timbers of their composure. Play he did, and though the match will be best remembered for John Lever’s outstanding first appearance for England, Willis very much and literally had a hand in his Essex friend’s triumph. You will recall that India had begun the third day at 51 for 4, needing 131 more to save the follow-on.

It was the crucial session. And for over an hour it seemed that India might play themselves back into the thing: Patel was looking cozily comfy, and little Gavaskar was middling enough to suggest even that he might ‘do an Amiss’ for India. It seemed that Lever, though continuing to bowl well, was on the point of coming off, then, at 96, Patel was gloved by the sprawling Knott down the leg side: 96 for 5. Within seven runs, Bob Willis had put England into lunch with the match surely sewn up.

All morning Bob Willis, Lever, and Chris Old had been casting some scrumptious bait for 18—Gavaskar’s hook. Now Lever dug one in; Sunil Gavaskar went for it without getting inside the line, and there was Willis, running full pelt round the ropes, 10, 20, 30 yards, to keep grip on a truly spectacular catch as he tumbled over. Ten minutes later, the last ball before lunch, and Sharma hit Underwood full off the meat; the ball cannoned from Greig’s thigh at silly point and Willis, this time in the gully, launched his full length like the amateur goalkeeper he once was to snatch the ricochet off the earth and into the scorebook.

The Indians were surely done for now. It was, in fact, the fielding of Bob Willis that first writ itself into our consciousness.

One could almost pick a team of men who have been flown out to bolster stricken English teams in mid-tour: Mortimore, Ted Dexter, Brian Statham, Colin Milburn, Len Hutton, even Chris Cowdrey. Willis did just that when poor Alan Ward, surprise, surprise, broke down during Illingworth’s ultimately successful march through Australia in the winter of 1971. ‘Willis who?’ we all cried when the Surrey beanpole, just 21, was sent from Heathrow. And with reason. In two itsy-bitsy seasons at The Oval, he had played but 16 first-class matches.

But he had taken 45 wickets, and even the sometimes-po-faced Wisden had to admit that ‘despite his odd method, he had made progress’. Anyway, there he was, sheepishly carrying his bag off the plane at Sydney. Illingworth played him in four of the Tests, nursing him like a proud mother hen. And his youthful zest off the longest run in the world brought him 14 Test wickets at 28 apiece.

But it was two memorably blinding catches close to the wicket in each of the Tests that were won that made his name as well as that of one or two photographers’. Back home, however, the young hero was forced to face the facts of life. Surrey were more than satisfied that Arnold and Jackman should continue to have first bite at the new ball. Willis’s control went to pieces. He thought at least that he deserved his county cap. After all, he’d helped win the Ashes, hadn’t he?

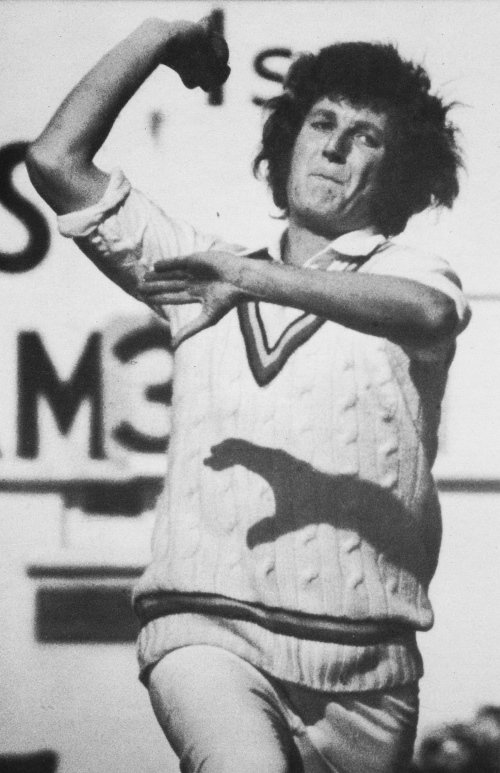

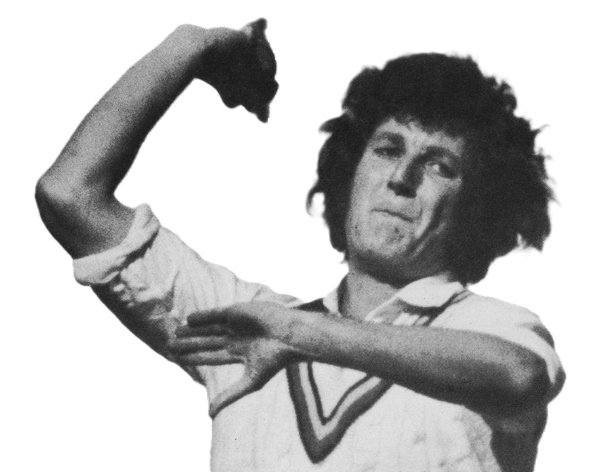

He brooded a bit, then upped and joined Warwickshire, who promptly won the Championship pennant from Surrey. He cut his run by over half when his pals told him he was just as fiery on Sundays, though his action remains as eccentrically exuberant as ever, full-faced and full-paced. For a time one felt he was going to join the litany of lost lanky loves who’ve had backs and knees collapse under the strain of opening for England. Bob Willis has had his operations and his osteopaths all right, but he’s come through them all with a determined will, always straining to get at the batsmen in that whirling, full-chested jingle-jangle of arms and legs—just like the Mr. Tambourine Man of his dearly beloved folk singer, Bob Dylan.

With all the reverence of a Catholic prep school boy choosing a saint’s confirmation name, he added his third initial to the R. G. Willis of his baptism by adding D for Dylan not long after he left Guildford Grammar School. On the misty November morning the MCC left for India, I went to the Clarendon Court Hotel to wish the team speed. Bob Willis had not, like others, spent the autumn in the nets, polishing his outswinger or breaking back.

He was just back from America, lying low and listening to Dylan on the sands of the West Coast. He needed the break. India has long, hot summers for a fast bowler. For that’s what he is, simply a fast bowler. And proud of it. He doesn’t, as Johnny Tyldesley once said of the fearsome Kortright, ‘go too much on swing comeback, or go-away. He just tries to bowl very fast—so’s not to leave time for anything else.’