Dilip Vengsarkar, then 19 years old, during the rain-marred Irani Trophy (Bombay vs Rest of India) match in Nagpur, October–November 1975. Bell, book, and candle—the traditional paraphernalia provided the eerie mood of enchantment for the witch’s cauldron that cooked the goose of the regular opening batsman.

The current form could not outweigh in-built prejudices and preconceived notions, and both Ramnath Parkar, scarily treated through the years, and Gopal Bose, left to lurk on the periphery of recognition, must have been left to wonder whether the Irani Cup match can truly fit the bill of a worthwhile pre-Test season trial.

The selectors seem to have their own norms and policies for spotting and encouraging talent. They have seldom shown imagination and courage, and there is no tangible evidence of a concerted effort to come to grips with the problems that face Indian cricket today.

The program and fixtures committee—tthe chairman of the selection committee is now an ex-officio member of that body —could be faulted for the thoughtless manner in which the annual four-day battle between the reigning Ranji Trophy champions, Bombay, and the Rest of India was allowed to overlap with the dates for the opening match of Sri Lanka’s tour of the country. The selectors could not possibly be at both Nagpur and Kanpur at the same time.

That turned out to be a minor aberration. What was moose to the point was the fact that the full panel of selectors was expected to name the captain for the unofficial series without really seeing either Bishen Singh Bedi or Sunil Gavaskar in action. Bishan Singh Bedi was given the nod before he even set a field or made a bowling change in a match in which the first eight-and-a-half hours’ play was lost through un-seasonal thundershowers.

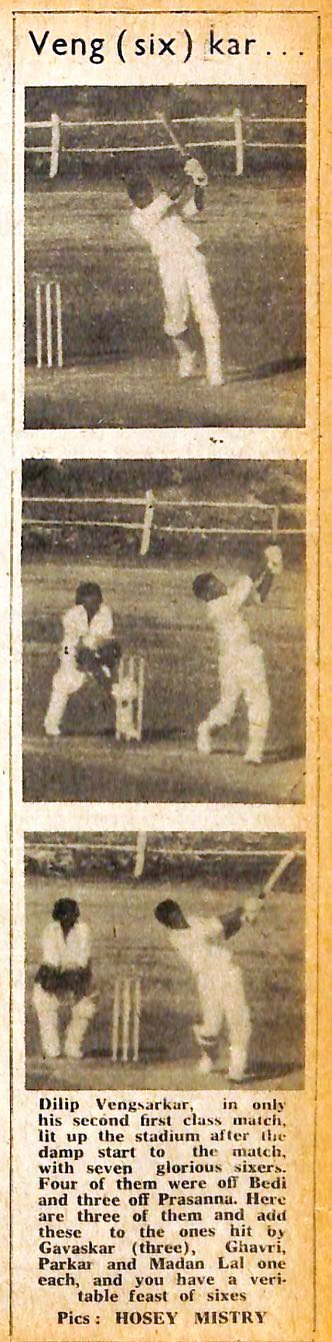

Dilip Vengsarkar (19), the most exciting batting prospect to hit the national scene since Gundpa Viswanath scored a century on his debut against Australia at Kanpur. And Sunil Gavaskar developed the knack of running into hundreds on the victory tour of the West Indies in 1971, bringing a breath of fresh air to the mildly stale atmosphere of a routine match in which the imbalances of the rest of India were aggravated by the inability of the injured Brijesh Patel to take his appointed line-up. Fortunately for Dilip Vengsarkar, a product of King George School and Podar College, the great utility lad, Eknath Solkar, remained on the injured list.

This made his place on the Bombay team secure, and he came up trumps with a hurricane hundred. Like St. Paul before them, the selectors were struck by the blinding light of revelation. But whether they will mold or hint into a suitable replacement for Ajit Midair as a one-drop batsman with the delicate artistry with which the potter’s trained hands shape clay is left to be seen.

Dilip Vengsarkar, a hard-hitting right-hander, used the rapier rather than the bludgeon to bruise and batter Bedi and Prasanna on an easy-paced pitch on which the ball turned slowly. His footwork is superb and his sense of timing is a sheer delight.

Prasanna and Bedi were snowed under an avalanche of fours and sixes as Dilip Vengsarkar hammered his way from one milestone to another. He reached his first fifty by dropping Prasanna in front of the sightscreen and treating Bedi in a similarly cavalier fashion, taking Bombay past the rest’s innings total of 210 and assuring them of their eighth success in one-match competition. The defending champions were Karnataka. Sunil Gavaskar, in magnificent form this season, and Ramnath Parkar who is stroking with firm confidence, laid the foundation for the eventual assault of Dilip Vengsarkar.

Ramnath Parkar was brilliant in the field, and yet he continues to wither on the vine, an unwanted or frozen asset. Gopal Bose tightened his defense and was troubled by the accuracy of Abdullah Ismail and the run-of-the-mill efficiency of Urmikant Mody, who was preferred to the leg-break googly bowler, Rakesh Tandon perhaps, Bombay took there from the West Zone selectors and introduced a left-arm medium pacer to maintain the socialist “leftist” image of the side.

With an additional medium-pacer in the side, Sunil Gavaskar had no option other than to put the opposition to the test. There was no devil on the pitch. But the damp and wet sawdust-bbathed outfield was slow, and nobody quarreled with Gavsakar’s decision.

It gave us an early opportunity to realize that Venkat Sundaram, who has curbed his exaggerated backlift a wee bit, is not technically equipped for the role of a dependable opening batman in the highest class of cricket. He still leaves a gap in his forward defense and soon succumbs to defeat. One was left to wonder about the mysterious sleight-of-hand trick that pitch-forked Sanjay Desai has a peculiar style and s into such company. He came in for the Injured Anshuman Gaekwad.