One of the trickiest questions is: Who was the best bowler David Gower ever faced? Inevitably, his mind turns to the quick men of the West Indies, who gave him the most torrid times of his career. Trying to pick one out, given all their strengths and differences, is not easy, but the palm would have to go to Malcom Marshall.

I was far from the only batsman of my generation who felt like that. And perhaps most persuasively of all, his West Indian peers rated him ever so highly. Andy Roberts and Michael Holding both conceded that he was probably the best.

I was far from the only batsman of my generation who felt like that. And perhaps most persuasively of all, his West Indian peers rated him ever so highly. Andy Roberts and Michael Holding both conceded that he was probably the best.

My respect and admiration for him were one of the reasons why, in 1990, I joined Hampshire, where he had long been an established star. Respect, admiration, and an instinct for preservation saw this as a sure-fire way to reduce the chances of me having to face his bowling.

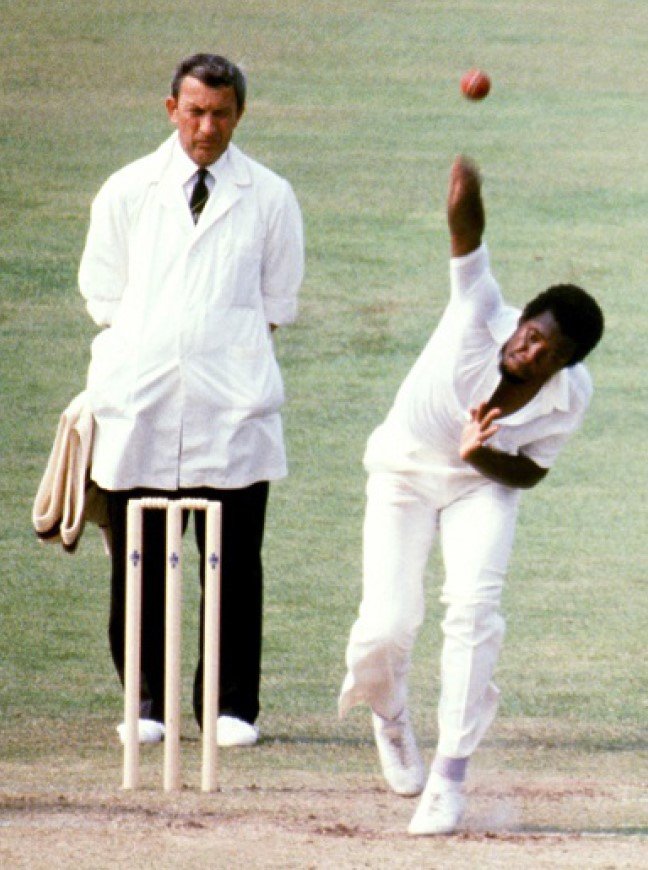

‘Macko’ had the blistering pace when he wanted it and could pepper you with bouncers when he felt like it. But he also possessed the nous to temper that pace when conditions suggested he would fare better by slowing down, pitching the ball up, and swinging it late both ways.

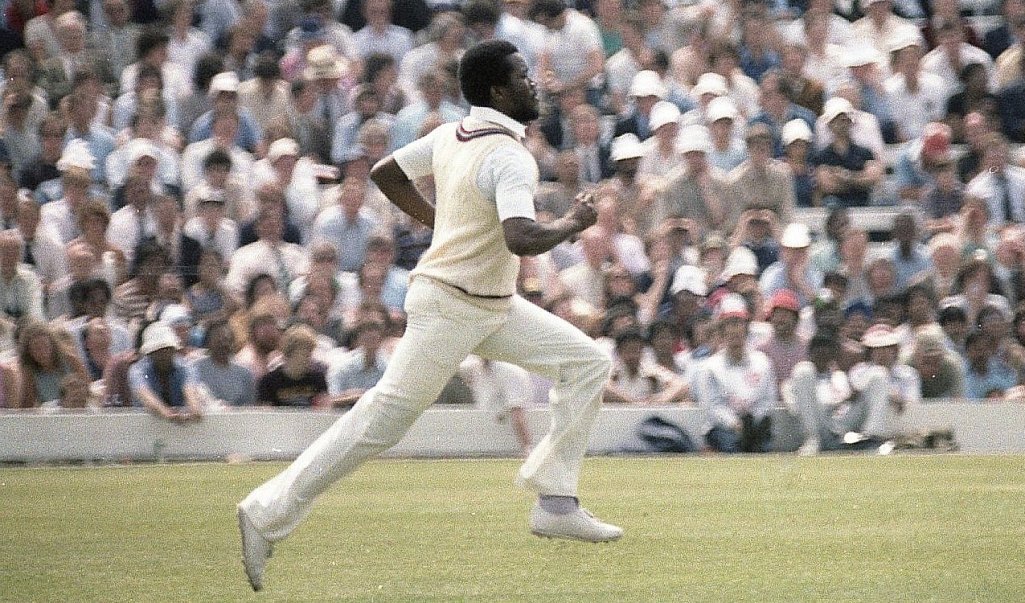

Everything about him was quick, from the sprinting run-up to the quick action to the ball that whistled around your ears. His instinct for assessing conditions was only matched by his knack for working out what tactics and field settings worked best for each opponent. He knew his mind and knew what he was trying to do.

He was among the sharpest of competitors. Andy Roberts was credited with, pardon the pun, marshaling the long line of great Caribbean fast bowlers of the 1970s and 1980s. But Malcolm Marshall took things to a new level of sophistication.

They know about fast bowling in Bridgetown and I remember once watching him from the stands there playing for Barbados in an island game. He was moving the ball around to the alarm of the batsmen in an exhibition that had a small gathering of locals looking on with me, purring their approval of a master technician at work.

What made him stand out? I reckon he was my equivalent of the previous generation facing Jeff Thomson in his pomp. ‘Thommo’ may have had a couple of miles an hour on Marshall, but at the speeds at which they were operating, that did not make a lot of difference.

The great thing about Thommo was that he would keep coming at you all day long, and he would keep getting a bounce. Marshall was the same: always coming. He had a lovely fluid action that disguised quite how much effort he was putting in, and it was amazing that he never seemed to get tired. You needed to be aware of that extra effort. He wouldn’t necessarily bowl at the speed of light all day, but he could step things up at any moment if he wanted to.

David Gower remembers Antigua in ‘1986, when England was battling to avoid yet another defeat at West Indian hands. I’d managed to bat a long time for 90 when, out of nowhere on a docile pitch, Marshall managed to bowl me a snorter of a bouncer—and one of those balls that ‘got big’.

In truth, I would contest the validity of the dismissal (honest!) as I was given out caught behind even though the ball narrowly missed my glove before flicking my shoulder. But it was the fact that Marshall had suddenly extracted so much extra bounce that produced the wicket.

Malcolm Marshall was relatively small for a fast bowler at 5 feet 11 inches, and this made him predominantly awkward. The Marshall bouncer tended to skid on you. If a taller man dropped the ball short, there was a fair chance it would go over your head.

But his best bouncers gave you nowhere to go and nowhere to hide. A lot of people, besides Mike Gatting, who once famously and painfully misjudged a hook shot against Marshall, found this out to their cost.

Malcolm Marshall broke my right wrist on that 1986 tour, although I didn’t realize it was broken until about a year later, when an X-ray showed another blow. However, this time, Merv Hughes, highlighted the damage. I just thought it hurt a lot. I first came across him on a Young England tour of the West Indies in 1976 and even though he was only 18 years old, it was clear that he was someone I might be coming up against a lot more in the future.

In fact, because of the emergence of the World Series, he was chosen to tour with the West Indies just two years later, after only one first-class appearance for Barbados. He had to wait a few years to become a regular on the test side. But his early promotion meant that he was able to learn on the job from some of the finest fast-bowling minds. He also learned a lot from joining Hampshire as a replacement overseas player for Roberts.

His breakthrough year was 1983, when he took 21 wickets in a home Test series against India before hot-footing to England to take 134 wickets in the championship for Hampshire (it is now almost 50 years since anyone took more wickets in an English season—Derek Underwood with 136 in 1967 was the last to have done so).

Shortly after, he took 33 wickets in six tests in what are usually arduous fast bowling conditions in India, having been given the new ball for the West Indies for the first time on the suggestion of Holding.

It was a role Malcolm Marshall relished and after that, he just got better and better. Even though he was playing in a mighty powerful attack, he regularly proved himself the dominant fast bowler on either side, never more so than during the 1988 series in England, when he took 35 wickets in the five matches at just 12.65 apiece.

West Indies never lost a Test series in which he featured and by the time of his last Test in 1991, he stood as the leading wicket-taker in West Indies history to that point (376 in 81 matches), with an average of 20.94 unmatched by any out-and-out fast bowler of the 20th century.

Malcom Marshall, raised by his mother and grandparents after his father died when he was an infant, grew up idolizing Garry Sobers, but his dreams of becoming a fully-fledged all-rounder never quite materialized. Even if he was a more than useful lower-order batsman (he scored seven first-class hundreds, but his Test best was 92),

Malcom Marshall was not only a great cricketer but also a lovely man who gave his all for the teams he played for. He was mortified at missing out on Hampshire’s cup final wins of 1988 and 1991, especially as he had also tasted defeat by one run in the Nat West Trophy in 1990, but this made victory all the sweeter when it came in the Benson & Hedges Cup in 1992.

There was never any element of him keeping things to himself; on the contrary, he enjoyed sharing information and this made him a wonderful coach in his later years, notably at Natal, where he mentored Shaun Pollock, among others.

Malcom Marshall’s early death from cancer in 1999 at the age of 41 was a desperate loss to all his many friends in the game and beyond. But he left memorable cricketing memories for their fans. He was a true legend of all time. Malcom Marshall, the menace, marshaled all resources and made the ball talk a language that was the dreadful dream of the world’s best batsman.

-

Read More

-

Sir Conard Hunte – The Greatest West Indies Batsman

-

Sylvester Clarke – A Bowler to Have on Your Side

-

Allan Rae – Classy Unsung Opening Batsman

-

Roy Gilchrist – A Violent Temper Fast Bowler

-

Roy Fredericks – Great West Indies Left Handed Batsman

-

50,000 Runs in all forms of cricket

-

Viv Richards West Indies, 1974 –1991