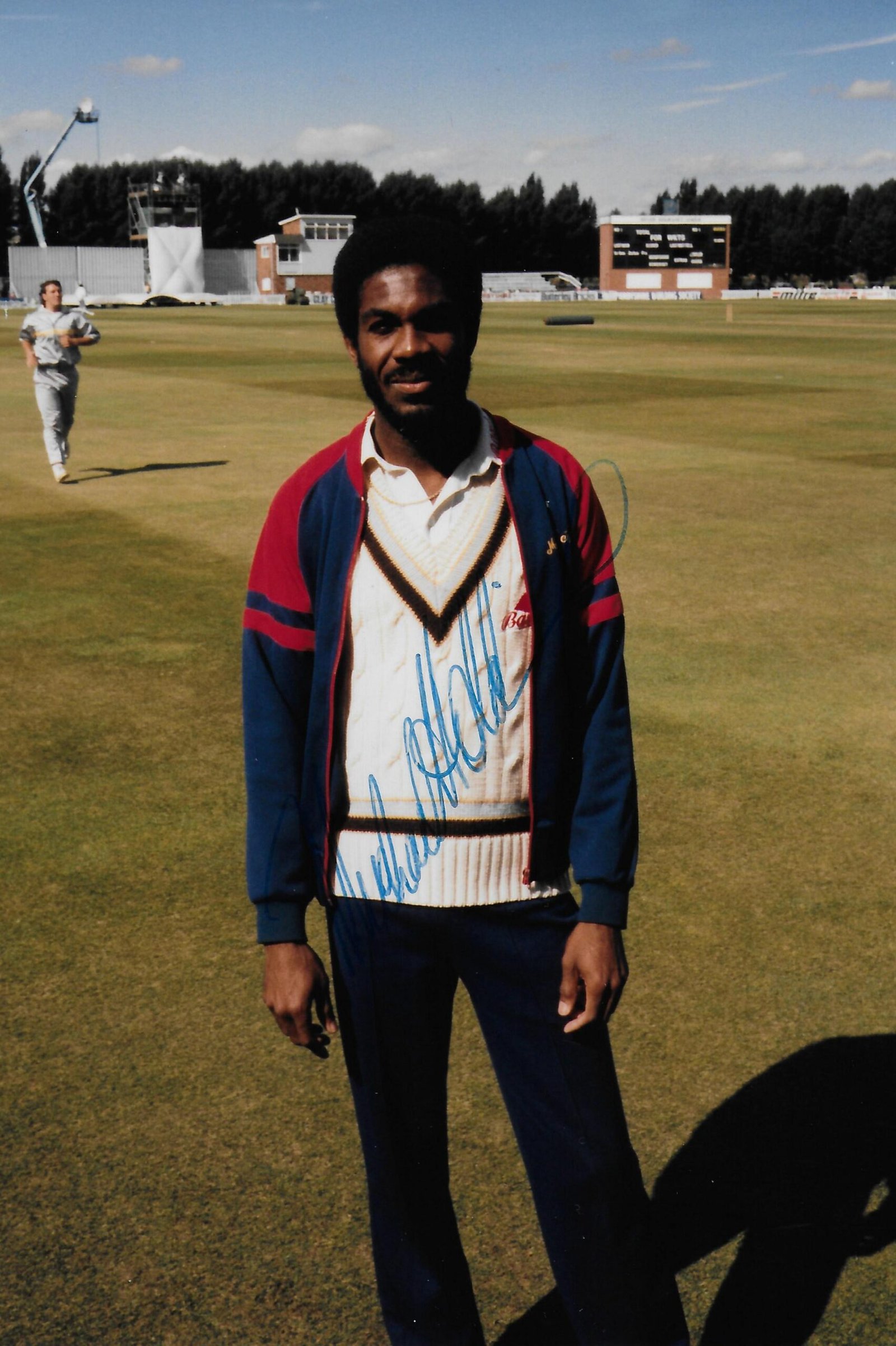

This article begins with a farewell to the whispering death of Michael Holding. Raymond Ford, who has known him since childhood, traces the development of the great West Indian fast bowler Michael Holding, who retired in September. As England goes through its soul-searching and packs its bags for the Caribbean tour, it might be of some consolation. Not that any member of the refanged West Indian pace pincer is to be taken lightly, but encounters with Michael in particular might be better off buried in the annals.

In his five-test series against England, Michael Holding captured 96 of his 249 wickets and, in addition, produced two of the finest displays of fast bowling prowess. Back in 1974, the year before Clive Lloyd gambled by taking him to Australia, I remember chatting with him at a party in Kingston. On that chilly night in Hope Pastures, there was a mission in his penetrating stare and baritone voice. I want to be on that ‘1976 tour to England’, he confided.

Not totally surprised, I inquired only about his stamina, not technique. ‘I am lifting weights at Mr. Goldsmith,’ came the response. I knew then that he was on his way. Indeed, he made that memorable trip, not as the inconspicuous rookie he had envisioned, but with 29 Test wickets from nine appearances. More importantly, he went with a reputation for pace that did not set well with frontline batsmen.

I first stumbled into this prodigy in the summer of 1964 at an unkempt site just behind his Dunrobin Avenue residence in Kingston. Red Hills Oval, as it was called, was more of a sociological garden than a nursery for the future West Indian player, so Michael Holding paid more attention to the daily cross-strata expositions than he did to cricket. However, when called upon to play, the critique was always positive, lively, and useful. Shortly thereafter, he began attending Kingston College High School.

Even though the school boasted West Indian caps in J. Cameron, J.K. Holt, Jr., ‘Collie’ Smith, and Easton McMorris, cricket at the time was dwarfed by successes both in track and field and soccer. In track, the school was just embarking on an extended dynasty, while in soccer, the 1964 and 1965 teams were arguably the best in the Caribbean. Michael’s success at schoolboy cricket would just have to wait until 1970, when his team went undefeated to island supremacy. It was during my seven years at Kingston College that I saw him in the making.

If I awoke early enough, I could ride with him to school as his father’s Chevy station wagon motored down Constant Spring Road. After classes, he seemed perennial to engage me in debates as to the shortest route on foot to cricket practice at the school’s Melbourne Park annex. Occasionally, on a Saturday evening, our paths would again cross in the environs of Maurice’s Restaurant. That was the place to savor a tasty curried goat or fried chicken, then wager the residual at ‘crown & anchor’—a game of chance. His preparation for the big leagues, though, was undoubtedly fashioned at the Melbourne Cricket Club in Kingston.

Under the tutelage of some former Jamaican representatives, Michael Holding moved smoothly through all three levels of club cricket and, in 1973, into the national team. After two inter-territorial seasons, Clive Lloyd had seen enough. Tossing statistics aside, he summoned Michael Holding for the ’75-76 sojourn in Australia. I can remember sharing that elation as his postcard from Brisbane read, ‘Don’t walk too hard; remember, I am down here, Mikey.’ The tour was statistically unflattering and yet so embryogenic to the West Indies’ success as we know it today.

Michael Holding, understudying Andy Roberts, had to partner raw pace with subtlety in order to dislodge the likes of Redpath and Turner. As he would later put it, ‘In bowling to the big bats, line-and-length alone is no good. It’s the variation that counts.’ His modesty wouldn’t allow him to mention his pace, even though he was bettering the much-feared Jeff Thomson at an estimated 97 mph.

The next tour, ‘Down Under’, four years later, was to bring him probably his most satisfying reward: the first Test series win for the West Indies there in six tries. In all, he would glean from Australia 73 Test wickets at 23 runs apiece and would leave us with some memorable duels against some eloquent batsmen. A connoisseur of batting technique, he still talks as if it were a great honor to have bowled to the two Chappells.

After the 5-1 drubbing, it was time to regroup against India at home. The humiliation had brought Lloyd’s leadership to scrutiny, and worse yet, when the series came to Kingston, it was still tied. Had the West Indies lost that particular match, Lloyd might have been doomed. Well aware of the situation, Michael produced blistering bowling, forcing Bedi to wave in surrender to umpires Gosein and Sang Hue. In the second innings, five of India’s batsmen were ‘absent hurt.’ What impressed me most, though, in his homecoming was to see him play that nerveless 55 when it mattered.

Both Bishan Singh Bedi and Chandra, their reputations notwithstanding, must have found his innings a trifle irreverent. As for the job of getting opening batsmen out, to him, India proved most obliging. In the three-test series he played, Michael Holding dislodged Sunil Gavaskar on 11 occasions and Gaekward on eight. One of the more memorable outings was served up at Sabina Park during the First Test in 1982. Pandemonium broke in the second innings as, with his opening delivery coming over the wicket, Gavaskar’s leg stump went cartwheeling. In spite of this success,

However, India was to inflict a major disappointment by snatching the 1983 World Cup. Like an axe for a brush, it seemed so muscled that a line-up would topple the 183 India had set. But alas, Michael was left to signal the celebration—lbw to Amarnath for six. Nevertheless, I will remember the level-headed conversation he entertained after that stunning defeat, a time when other cricketers may have been understandably unapproachable.

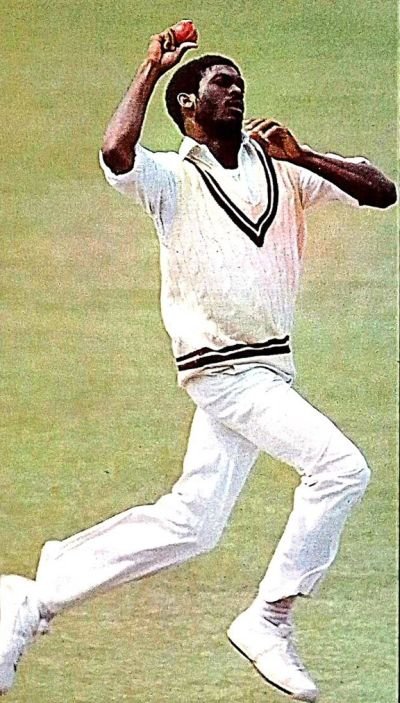

It’s now the summer of 1976, and on to the lushness of England—for him, the dream had come true. Even before the Duchess of Norfolk welcomed the party to Arundel, tales of his exploits in Kingston had washed ashore. The hosts were already scurrying for some brave men. The series belonged to the West Indies before the Fifth Test began at the Oval. The pitch there was so placid that both sides pledged double centurions. This was the setting that Michael Holding chose to generate an unbelievable pace to return match-winning figures of 14 for 149.

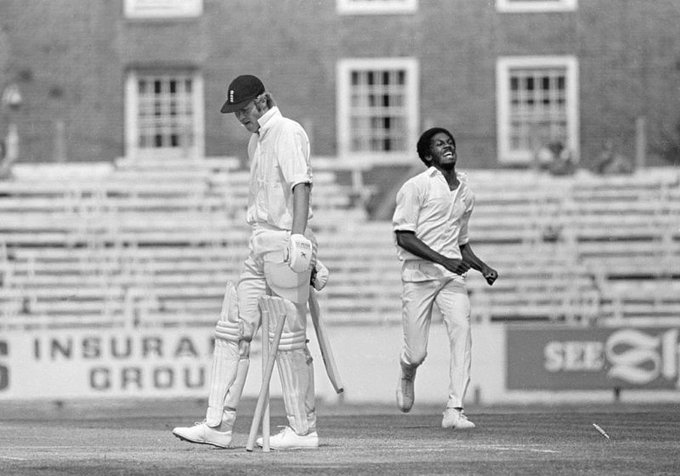

The press spewed superlatives. The heroic performance against England isn’t over yet. Five years later, the two teams again meet, this time in the Caribbean. It didn’t seem that 13 years had passed since we were huddled over radios as Gary Sobers trapped Boycott LBW for 90 in that Third Test in Barbados on the ’68 tour. That same batting technocrat, now armor-clad, is still run-ravenous. He makes his way onto the same ground to open against the West Indies for the 46th time.

Little does he suspect that the six deliveries he is about to receive from Michael Holding will be dubbed by many as six of the most testing ever bowled. The resident second slip remembered the sequence: “The one that bowled him wasn’t as quick, but the first five—good God.’ By the time England again visited in 1986, signs of Michael’s departure were eminent. The left hamstring injury hobbled him in the Kingston Test, and yet he limped past his truncated mark to treat the crowd to that patented glide one more time. He knew for sure that it was time to go. While the West Indian captain drew on his victory cigar, Michael Holding begged to be excused from going on to Trinidad but asked to rejoin the tour in Barbados.

The West Indies Board, however, publicly chose to dissuade him from retiring. Resting him from the next tour to Pakistan, it included him for both the World Series in Australia and the Test series in New Zealand. Every sportsman, it seems, has a nemesis. From the onset, New Zealand was his. Anxious to return home after the historic win in Australia, the team detoured there to play three Test matches in 1980. Frustration, not entirely unprovoked, elicited his ill-temper in Dunedin. The hosts went on to eke out the series 1-0.

With hindsight, he might not have allowed himself to be lured back. This man is a true professional and does not pride himself on abandoned jobs. As fate would have it, his fitness failed in the First Test in Wellington in 1987. The 16 Kiwi Test wickets, in the end, cost him 34 runs each, a little more than his usual asking price. Derek Randall (right) leads the Nott’s applause as Michael Holding leaves the first-class cricket field for the final time, having steered Derbyshire to an exciting one-wicket victory with an unbeaten 13.

Michael Holding’s career has nevertheless been a remarkable one. It came along on the leading edge of the West Indies’ newly found professionalism and enhanced pecuniary reward. In that same era, the territory’s cricket weathered trying times as it juddered through the Kerry Packer schism and South Africa’s tainted lucre lure to emerge stronger. Clayton Goodwin is all-encompassing in writing: ‘Michael Holding provided an unprecedented blend of skill, artistry, devastation and technical perfection.’

Michael Holding the person, Dennis Lillee might be justified in writing, ‘Many have probably looked for a way to dislike him, but it’s impossible.’ As my acquaintance endures, I continue to esteem his independent thinking and straightforwardness. At Sabina Park, we will certainly miss those stoic walks towards us as we watch him eye the ball like a looped jeweler. All this before he turns away to transform that innocuous jog into that effortless sprint. But as the catching cordon prepares to rivet its attention, let me turn you over to those gallant warriors peering from behind their grilled masks.