The Infamous Mike Gatting and Shakoor Rana Incident-England team arrived in the middle of October 2000 for a tour of Pakistan. It was the first since the famous Mike Gatting brawl with umpire Shakoor Rana during the ill-fated 1987–88 Test series. The men in the middle of that drama recall the incident, and Mike Selvey offers his version of events. Basically, the interviews that follow and the Paul Weaver article taken from The Guardian provide the English point of view.

Mike Gatting England captain “I really don’t want to inflame old wounds and make things difficult for the team when they get to Pakistan. It wasn’t an easy tour; everyone knows that, and they can all draw their own conclusions. We were not the first side to experience difficulties. The New Zealanders walked off the field, and so did India.

I think Australia came close to it. I’m not saying we were the catalyst for it but a lot of things have changed now with good facilities for practice, match referees, and independent umpires. It was hard when we switched from the World Cup, which was excellently organized, to the tour. Shakoor Rana Pakistani umpire “I do not regret what happened.

England should regret it. They lost a day’s play from a match they were winning. Mike Gatting is not a cheat. But that day in Faisalabad, he cheated. I don’t know why. I think he lost his temper after losing the first Test in Lahore. And after cheating, he started abusing me. It was sad about what happened. Today, the match referee would sort it out. But he wrote me an apology, and now it is a closed chapter. I would never have agreed to apologize. Why? I was 100% right.”

Peter Lush England team manager said: We tried to get the problem sorted out overnight, and on the third day it looked like a solution had been reached, but it all fell through. I needed to talk to the Pakistan Board secretary, Ijaz Butt at that stage, but he had decided to go back to Lahore, so that evening I drove there myself with the aim of speaking to him and the board president, Lt-Gen. Safdar Butt, about providing alternative umpires if these would not stand.

It was a terrifying journey down that road at night but also a curious one because in the car with me was Javed Miandad and I remember thinking that things could not be too bright, as he ought to have been on the ground. “For some reason, the general was not available when we reached Lahore, and I had to spend the night there before meeting the next day with him as well as Ijaz Butt and Haseeb Ahsan.

It was supposed to be a private meeting, but two journalists arrived and a radio fellow, and interviews were conducted. I was told by the general that it had all been sorted out and that the impasse had been solved, but of course it hadn’t. I returned to Faisalabad and nothing had changed. “We felt very isolated.

There was no one to turn to, and time was against us. Calls home had to be booked, so that was difficult, as was the habit of officials suddenly switching their conversations to Urdu so that we could not understand them. I can’t recall anything worse in my experience. It was all very harrowing. Haseeb Ahsan, Pakistan team manager, said, I arrived in Faisalabad at 2 a.m.

I had been asked by the Pakistan Cricket Board, at the behest of England tour manager Peter Lush, to mediate between Mike Gatting and Shakoor Rana. I told Gatting that the umpire was the boss and that he had been insulted. All he had to do was apologize.

Then England would have gone on to win the match. “The problems were partly the result of the World Cup, which had been a disappointment for both teams Gatting had played that hopeless reverse sweep in Calcutta when England lost the World Cup final to Australia.

And there had been bad feelings between players and umpires on both sides for years. I was heavily involved in Pakistan’s fight for neutral umpires and match referees, and I’m proud that their introduction began to put things right. “I don’t anticipate any problems this time. Nasser Hussain is a refined person, and most of the England players accompanying him are sportspeople.

The ICC code conducts a meeting to ensure that mist-having players is no longer tolerated “England’s 13-year absence from Pakistan is too big a gap. We need England’s teams to set a good example; I’m sure this time they will.” Chris Broad, the opener for England, says, I batted for a few hours in the first innings of the Lahore Test and saw plenty of strange things from the non-striker’s end.

There were at least four decisions that I couldn’t believe. So, then came the second inning and another opportunity for the umpires to get involved in the game. I was given out and caught behind by Shakeel Khan. It was an unreal situation: I didn’t hit the ball, and I’d never experienced that sort of thing before.

I didn’t see why I should go, so I stood my ground. In hindsight, I’m not very proud of what happened but I should imagine some of the Pakistanis are not very proud of the way they behaved either. “Eventually Graham Gooch came down the pitch from the non-striker’s end and told me I had to go. There was nothing I could do.

The strange thing was that, even though there were five minutes to go until tea, the umpires removed the bails and walked off. At Faisalabad, I wasn’t within a near shot of Gatting exchanging words with Shakoor Rana. But I believe his version of events, and certainly he had the full support of his team.

Not many people remember this incident, but I actually scored a century in that Faisalabad Test. So, one of the more forgotten hundreds “Time heals, and I suppose I can smile about things now. Nothing like that will happen again, because there are neutral umpires and match referees, and I know the Pakistanis are keen to make England feel welcome this winter.”

Graham Gooch was Broad’s opening partner. “The problems in Faisalabad were on the back of the first test in Lahore. I was batting at the other end of Chris Broad when he staged his protest. We were seeing a bit after Shakeel We had won the three one-day matches 3-0, so we went into the test series feeling pretty confident.

And they were without Imran Khan, too. Mind you, Abdul Qadir bowled so well on pitches that suited him that Pakistan might have won the series even if everything had been normal. Shakeel Khan, the umpire, had seen us off in the first inning. Iqbal Qasim was bowling his slow left-arm spin from over the wicket.

A ball went past the outside edge; there was a noise, and they all went up with a big appeal. Shakeel gave him out but Broady just stood there and said: I’m not going for that.’ They all went into a huddle and had a few words with him. After about half a minute, I wandered down to him and said, ‘Loot, mate, I think you’ve got to go and get rid of him. On reflection, I should have left him there, and then we could all have gone home.

The Shakoor Rana thing was a storm in a teacup. Really, we thought he’d nicked that lunch; that was all. We actually took to the field the next morning, expecting them to come out. We ended up sitting around on the roller, waiting. Later, we had a meeting, and the players were solid in not wanting to carry on with the tour.

As one of the more experienced players, I told them they would be in breach of contract and should consider what it could do to their careers. We compiled a statement and then took the field. David Capel, the England all-rounder, said it was a tour I shall never forget. The first two matches, in Lahore and Faisalabad, were only the second and third Tests of my career.

In Lahore, I didn’t touch the ball with my bat in the entire match. However, I was twice given out and caught. Therefore, of my four dismissals in those matches, they got me out properly, just once. Indeed, it was unbelievable stuff. Of the first 30 wickets, we lost; we reckoned that we had been “sawn off” on about 15 occasions. And we always felt that to take 10 of their wickets, we really had to take 15.

We had won the three one-day matches 3-0, so we went into the test series feeling pretty confident. And they were without Imran Khan, too. Mind you, leg spinner googly bowler Abdul Qadir bowled so well on the turning pitches that suited him. Pakistan might have won the series even if everything had been normal. It was a pity what happened in Faisalabad because the incident came right at the end of a long, hot day, the penultimate day of the second day.

If we had been able to avoid a big scene, we were in a winning position. “Mike Gatting called me in from deep square leg and told the batsman, who was Saleem Malik. But Shakoor Rana accused him of cheating and used swear words that I had not heard from an umpire before or since.

They should let sleeping dogs lie and go into the series with a positive attitude. Shakoor says England has no chance of victory. Although Shakoor Rana says Mike Gatting is his favorite cricketer and that he is welcome to stay with him in Lahore, But after 13 years, the umpire still persists with the outlandish claim that the England captain was cheating when Anglo-Pakistani tensions exploded at Faisalabad, writes Paul Weaver.

A gloriously unrepentant Shakoor, 63 and now an assistant sports officer with Pakistan Railways, also says England “cannot win” in Pakistan; they have attacked the decision not to tour the country in the past 13 years. I do not know why England does not come,” he said. It is not my fault. But it is England’s bad luck.

If they had come to Pakistan, they might have learned to play spin bowling, which they can’t. I do not regret what happened. England should regret it. They lost a day’s play from a match they were winning. How can I regret it? It made me the most famous umpire.

People don’t recognize me now, but when I introduce myself, everyone says, ‘Ah, yes, the famous umpire. Infamous might be more appropriate. It was awful umpiring, most notably by Shakoor Ran in 1987. Shakoor and Shakeel Khan paved the way for neutral officials and helped dissuade England from touring the country.

On October 16, they returned for the first time for an official tour. “Mike Gatting is a good person, said Shakoor, who even before the England series 18 years ago kept a proudly thumbed cuttings book in which he was described as “The World’s Worst Umpire.” “He is my favorite cricketer.

He can play spin bowling if he comes here I would like him to be a guest at my house. He is not a cheat. But that day in Faisalabad, he cheated. I don’t know why I think he lost his temper after losing the test in Lahore. And after cheating, he started abusing me. My code of honor allows me to kill a man who insults me. “But he wrote me a note of apology.

I used to keep it under my pillow. Now I have it in a drawer. But it is a closed chapter. “I came to England a few years ago to see my son, Mansoor, who was playing in the Bradford League. I saw Gatting sitting in a car. I went over because I wanted to talk to him and shake his hand. But he said, ‘Oh God, not you again,” and drove off.”

Even by the Byzantine standards of Pakistani cricket, the tour of 1987–88 was something else. It was probably the most acrimonious series played since Body Line. Even that schism of 1932–33 was followed by another England tour to Australia four years later. The furious, finger-pointing exchange between Shakoor and Gatting was more than a mere cricket row.

They stuck the picture on front pages all over the world, even in Germany. There were colonial overtones. And the image of an angry England captain at odds with a foreign umpire was symbolically represented as another sign of a once-great nation’s terminal decline.

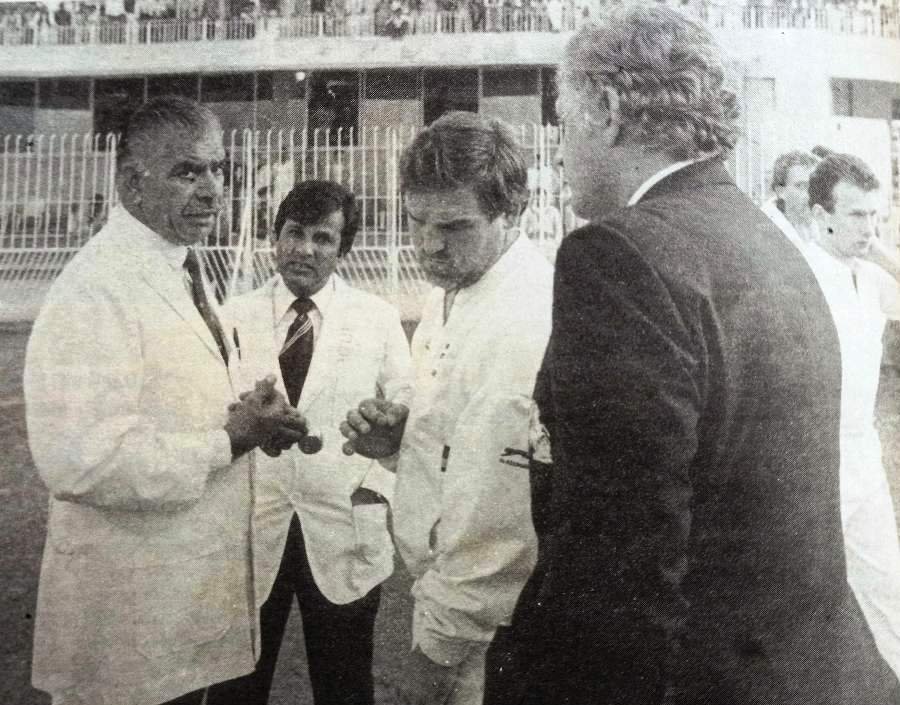

The flashpoint came at the end of the second day of the second test in Faisalabad. When England captain Mike Gatting signaled David Capel to come up from deep square leg to save a single, he had, he said later, informed the batsman, Saleem Malik, of the field change, though this had increasingly become the job of the non-striker.

Then, as Eddie Hemmings came into the bowl, Gatting put his hand up to tell David Capel he had come in enough. Shakoor, standing at square leg, stopped play to tell the batsman about the fielder’s position and then accused Gatting of cheating. An ugly row followed, and the following day, Shakoor said he would not play unless he received an apology from Gatting.

A mutual apology was brokered before the Pakistan captain, Javed Miandad, persuaded Shakoor to stand firm. Mike Gatting eventually issued an unreciprocated, scribbled apology on the understanding that he could tell everyone he had been made to do it by the England management. The third day’s play was lost. Shakoor contradicts this version.

I would never have agreed to apologize,” he said. “Why? I was 100% right. The Pakistan tour in 1987 was the most taxing leg of an arduous winter that also included a Test series against New Zealand. A World Cup and the Bicentennial Test against Australia were held in Sydney, and those of us who were in Pakistan soon realized that England would not be allowed to win the series.

Pakistan, it seemed, had decided to exact revenge for the previous summer when they toured England and vainly requested that David Constant and Ken Palmer be removed from the panel of Test umpires. In the first Test of 1987–88 in Lahore, England was convinced that they were cheated out of the match.

The tone was set when Gatting, playing a sharp leg break that pitched off-stump, was given out by Shakeel Khan. According to the England players, this was one of nine bad decisions that went against them. They lost by an inning and 87 runs; we weren’t allowed to perform,” Gatting said. The worst was to come after the flagrant umpiring that cut us short. Shakoor was appointed to stand in the second test.

England asked me not to select Shakeel Khan,” said Pakistan’s unofficial manager, Haseeb Ahsan. “Let’s see how they like Shakoor Rana.” Shakoor already had a reputation as the world’s most obstinate umpire. In 1978–79, in Faisalabad’s first Test match, he held up play for 13 minutes while he argued with India’s Sunil Gavaskar.

And in 1984–85, he provoked New Zealand captain Jeremy Coney to lead his players off the field in protest. Shakoor dismayed Gatting’s players by wearing a Pakistani sweater, and when Mudassar Nazar handed him his cap prior to bowling, he promptly put it on.

But Shakoor’s actions backfired. He officiated in only two Test matches after the Faisalabad affair. I don’t even go to cricket matches now. But I watch them on TV with my grandson. And I will watch England. It will be a win at all costs for both sides. It is always sad to remember what happened before. Today, the match referee would sort it out.

At Worcester during the Middlesex’s Refuge Assurance Cup semi-final, former England captain Mike Gatting had an unexpected meeting with Pakistan umpire Shakoor Rana, with whom he had a fierce on-field row during the Faisalabad Test in December 1987.

The Sun reported that Mike Gatting is saying, ‘Oh God, no. Not him again. He refused to shake hands or speak with Rana Wo said, “He should have shaken hands, if only for cricket’s sake. Then we could have had a cup of tea.

Mike Gatting and Shakoor Rana’s incident completely changed the idea of local umpiring. Shakoor Rana was an average player; he played 11 first-class matches between 1957 and 1973, scoring 226 runs and taking 12 wickets. He died on April 9, 2001, at the age of 65. His brothers Shafqat Rana and Azmat Rana also played Test cricket for Pakistan.