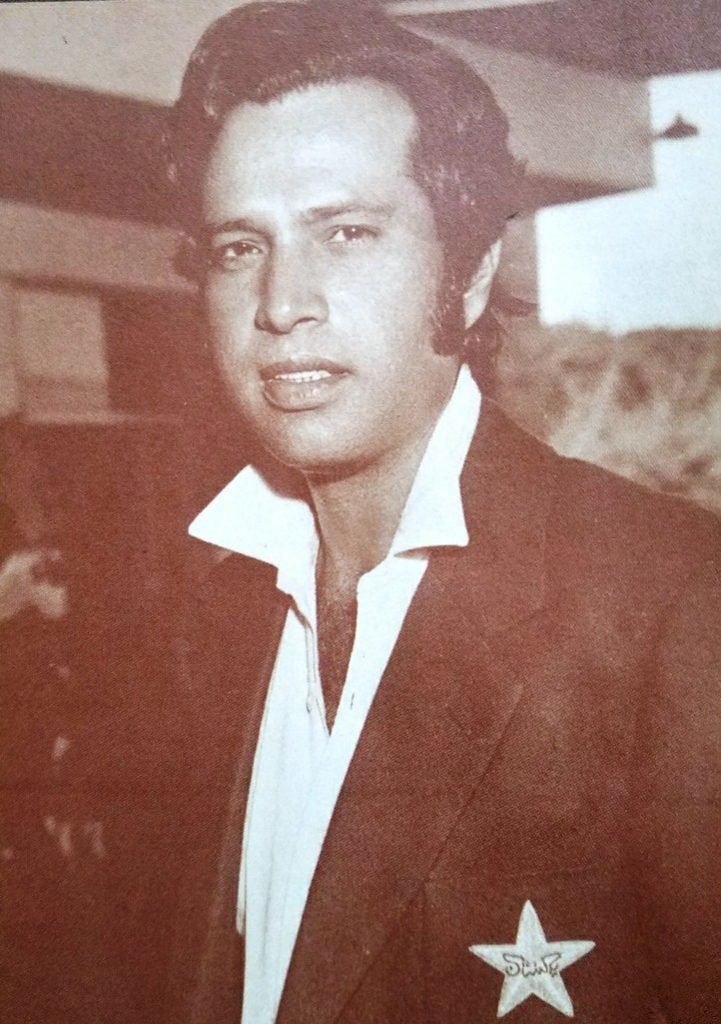

One of the primary reasons Saeed Ahmad did not receive the recognition he deserved was to do with his achieving very little on three English tours. Admittedly, he did not fulfill his potential after his spectacular entry into Test cricket against the West Indies in 1957–58. But in his first years of Test cricket, he even overshadowed the great Hanif Muhammad, both in terms of stroke play and consistency.

But suddenly Saeed (Sidi to his close associates) went off-color and was to perform only in patches. The latter half of his career was also littered with one controversy after another. The cricket administrators in Pakistan had a rough time handling this temperamental individual on each of the last four tours that Saeed Ahmad accompanied the team on.

His political ambitions did not serve him well either, and his tenure as Pakistan’s captain only lasted a few months. His last tour to Australia in 1972–73, he was left behind by the team management for another disciplinary problem. It came as a great surprise to hear that this colorful cricketer personality of the past has devoted him so wholeheartedly to religion. Presently, Saeed is a regular face at Islamic gatherings in Pakistan.

The brilliant start to Saeed’s Test career was only matched by Javed Miandad among the Pakistan batsmen. Brought up on hard-batting wickets in Lahore, he could not have asked for a better introduction than to have the opportunity to tour the West Indies.

Throughout the series, he employed his upright stance and range of blazing off-side stroke play to good effect. By the time he had finished the Indian tour, three years later, his career figures read 1501 runs scored at an average of fifty-plus. Cricket pundits were hailing him as one of the batsmen to dominate the international scene in the 1960s.

But sadly for Pakistan cricket, the bright batting star failed to live up to the high expectations. Although Saeed Ahmad has played 38 consecutive Test matches since his debut, his technique was exposed both on tours of England and New Zealand.

To trace Saeed Ahmad’s ancestors, one has to cross the Indian border into Punjab’s major town, Jullundur. He was born on October 1, 1937. Saeed Ahmed was one of the ten children fathered by Mr. Inayat Ullah Ahmed, who in his later years served as a labor officer at the Pakistan High Commission.

Although he himself was a keen follower of the game, Inayatullah wanted Saeed to pursue engineering as a career. It is not clear whether Saeed took up cricket while at Central Model High School, Lahore. But his batting exploits at Islamic College, where he passed his BA in 1961, were clear signs of his sport-oriented mind. By then, he was also a regular member of the Universal Cricket Club in Lahore. Because one leg was shorter than the other, he was better known as Saeed Dooda. The handicap apparently never bothered him personally, though.

Although he had entered first-class cricket at the age of 17, it was not until his fourth year that selectors had any reason to take a close look at him. Saeed Ahmed has attended a six-week university training camp organized by the Pakistan Sports Control Board. He recalls looking back now and feeling that I was lucky, I went to the camp because, among others, it was directed by Captain Abdul Hafeez Kardar. At the time of the preliminary selection of the team for the Bahawalpur training camp, I was not so sure that I would be selected. It was, however, through the counsel of the other selectors and the strong recommendation of the skipper himself that I was included.

It came as a surprise for Saeed when he was not considered for the Punjab side in the initial matches of the 1957–58 domestic seasons. When given the opportunity, he made the most of it with an unbeaten hundred against Punjab B. This inning assured him a place in the Bahawalpur training camp and a step toward his ambition to represent the country. The camp was ideal preparation for a 20-year-old youngster hoping to embark on a major overseas tour.

He utilized the three-week training period in Bahawalpur to learn to control his natural inclination to hit the ball. The physical training helped me to build my stamina, which was the result of my time on the West Indies tour. I played all the matches, but the strain did not do well for my health. It is interesting to mention that Saeed was picked for the No. 3 spot. Which meant he was to compete with Waqar Hassan, who had been an instrumental figure in his formative years.

It was Waqar who persuaded Saeed’s father to let his son continue with the game. From the very start of the West Indies tour, Saeed Ahmad outscored his senior colleague and cemented his place for the next decade. Two triple hundreds of varying significance, i.e., Hanif Muhammad’s marathon 337 at Bridgetown and Gary Sobers world record score of 365* at Kingston, dominated the 1957-58 series between the West Indies and Pakistan. But with his incredible consistency in all five Test matches, it became impossible to ignore Saeed.

He started with 54 against Barbados and continued his run spree with dashing stroke play. In the fourth Test match at Georgetown, he reached his first hundred and was finally out for 150 in his team’s total of 408. As opposed to senior batsman Hanif Muhammad, Saeed had shown a lot of courage against the pacemen. His infarct had problems of a different sort. In the previous Test innings, he had failed to capitalize on a good start by each time getting out to the spinners.

Saeed Ahmad was determined to make up for his earlier lack of application in what was batting paradise. It was a great pity that his timely knock failed to save the series for Pakistan. They were depleted, and blowing the attack allowed the opposition to reach 317 for the loss of only two wickets on the final day. In the final Test, Saeed Ahmad missed his hundred by three runs.

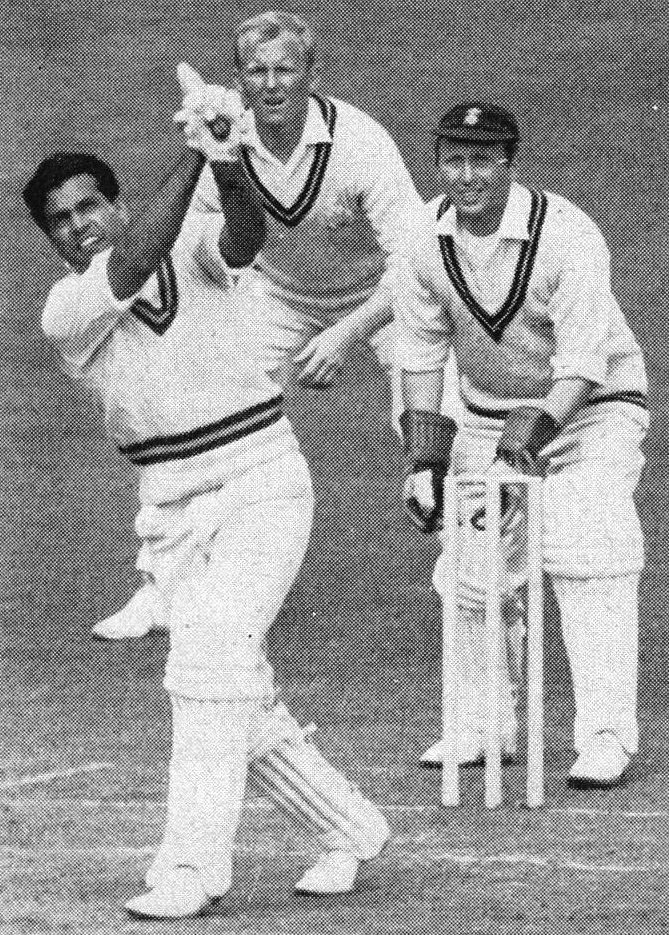

So, on this occasion, it contributed to a match-winning total. Wisden summed up his successful tour. Saeed Ahmad is a young batsman of attractive, upright style who is also a hard driver. He has the ability to score readily and seems like a player with a big future. Regardless of the situation, he would not curb his natural aggression. What a pleasant sight he was on the tour! He was without question the find of the tour.

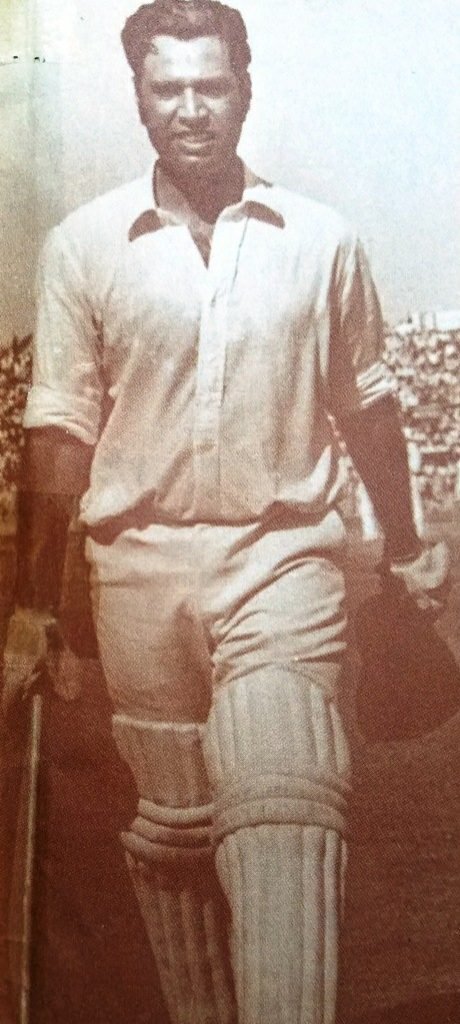

It was at the new Lahore stadium, now called Gadaffi Stadium. Saeed played his most memorable inning for Pakistan. The home side had lost the opening Test to Richie Benaud’s side on the 1959–60 Australian tour. A similar fate for the home side at Lahore when they finished 245 runs behind in the first inning. In their second innings, Pakistan was 87 for 2 when Shauja-ud-din joined Saeed Ahmad for their historic partnership that almost saved the game. The pair defied the opposition attack for more than five hours and added 169 runs for the third wicket.

It was a questionable leg before the decision against Shuja that separated the two. His partner, Saeed, who had batted throughout the fourth day, was dismissed early on the final morning. While stretching forward, left-arm spinner Lindsay Kline lost his balance and was stumped.

His marathon effort, worth a career-best 166, lasted for 457 minutes and included 19 fours. In the end, this was the case with his first hundred in the West Indies. Saeed finished on the losing side. In the last Test of Karachi, Saeed Ahmed completed thousands of runs in only his 11th Test, a record that has not been battered by any Pakistani batsman.

By now, Saeed Ahmad was a permanent fixture in the Pakistan team. He faced very little competition for his No. 3 position. However, Saeed had a relaxed, upright stance with no hint of crouching. Nimble footwork and flashing off-side play were the key features of his batting that drew the crowd in plenty. Most of his runs were collected from strokes executed on the offside.

Saeed Ahmad was not a great hooker, but he found it hard to resist a short ball and invariably used to get away with it. A stroke that fits well with his arrogant style makes him a batsman. Saeed was always his happiest when attacking and made no secret of his likeness for bouncy wickets. It is a pity that, at the peak of his career, Pakistan was hardly a cricketing force to have been invited to these parts of the world on a regular basis.

His colleague, Shuaj-ud-din, recalls Saeed’s batting. I considered Saeed a very lucky player throughout his career. His flashing strokes generated great power, and he used to get away with hard chances. I remember Richie Benaud posting two gullies and a fly-slip for him, but to no avail. Even that did not stop him from playing his favorite strokes. Given space, he was a ferocious cutter, and his drives were very punchy. Technically, he was not a very sound batsman, with little emphasis on footwork. He relied on his wrist and quick eye, not to mention his natural aggression. It was indeed very pleasant to watch him.

It is perhaps fair to say that Saeed’s bowling talents were not adequately utilized by any of the Pakistan captains that he played under for. Although his off-spin was hardly of traditional merit as far as flight and deception were concerned, he was pretty useful in domestic cricket. He was adamant, and Saeed Ahmad was underrated as a bowler. A fine bowler used to spin his body more than the ball.

He had a good cricket brain and used to confuse the batsman with his floating off-breaks. Which he often straightened used? It is no surprise that his best Test series as a bowler was against England in 1968–69, while he himself was in charge. Admittedly, in the early sixties, Pakistan did have a spinning stock of useful quality in Nasim-ul-Ghani, Haseeb Ahsan, Intikhab Alam, and Pervez Sajjad. A well-thought-out strategy would have included Saeed as a support option.

By having Saeed as a second spinner, perhaps Pakistan could have fielded a more balanced side in that period. Against Ceylon in 1966–67, he took 10 wickets for 130 runs in an unofficial Test at Dacca. However, Mushtaq Muhammad took eight wickets among them. He was also a good cover fielder.

Saeed Ahmad Tour to India in 1960–61

On his second overseas tour to India in 1960–61 in national colors, he once again finished as the most confident and polished Pakistani batsman. He hit two sparkling hundreds in a series that was marred by defensive tactics from both sides.

In the first Test at Bombay, Saeed Ahmad scored a brilliant century of 121 and added 246 runs for the second wicket with Hanif Muhammad (a record at that time). During his innings, he was bitten on the head by Ramankanth Desai, and the ball flew to the boundary.

Saeed Ahmad did not even bother to rub, and he hooked the very next ball for six. Although impressed by Saeed Ahmad’s innings, Qamar-ud-din chose harsher words for his self-inflicted dismissal on the second morning.

It was also comforting from the Pakistani viewpoint that he should have capped his performance with a century. Notably, his career drives off the back foot, wherein the leg and the forearm generated power were so much to the crowd’s taste.

But I’m afraid Saeed’s manner of dismissal was a very poor reflection on the otherwise sterling innings. It ill-beloved him to make that dash to Gupte’s innocuous ball and offer his wicket on a platter.

Saeed Ahmad also scored a hundred in the fourth Test match in Madras, followed by a better reaction from the same author. He was spotted as a cricketer of class in the West Indies and is now a finished article, an experienced, balanced, fully organized cricketer who must reign in the cricket scene for a long time to come.

Saeed Ahmad on the Tour of England in 1962

On his first tour to England in 1962, Hanif Muhammad struggled because of an injured knee. Saeed Ahmad had an opportunity to outshine the little master, but his technical deficiencies on English seaming wickets proved his downfall. His basic fondness for cross-batted strokes and the square of the wicket on either side didn’t prove effective enough.

He was also found wanting on the balls leaving the bat. Though his tally of 302 runs in the five Tests was second only to Mushtaq Muhammad, the general opinion was to the effect that Saeed, with the better application, was capable of taking his team out of the crisis.

One of his three fifty-plus scores came in the fourth Test at Nottingham, which helped Pakistan save the Test match. But Javed Burki’s doomed side lost the series with a massive 4 nil. Wisden was critical of the team’s front-line batsman, Saeed Ahmad, who, at the age of 24, showed much promise. With more concentration on the task at hand, he could be a real asset to Pakistani cricket. It was during this tour that Saeed was reported to have established some friendships outside the cricket scene that coincided with the downward graph of his batting skills.

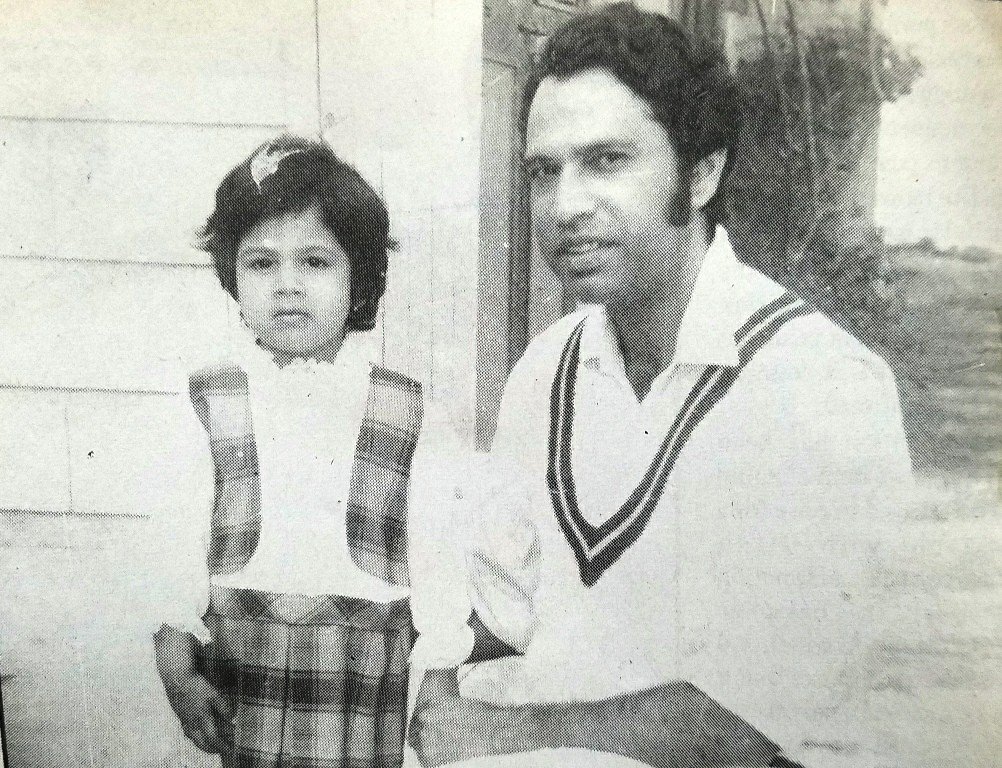

After the England tour, he got married to Salma Ahmed, a leading businesswoman in Karachi, by whom he had two daughters and a son. With her powerful influence in an affluent society, Saeed was introduced to the political scene. Once he had become a cricket star, his lifestyle became extravagant for a man of a relatively poor background. In Karachi, he joined the City Gymkhana Cricket Club in order to stay in touch with the game in the offseason.

He was keen on making the most of it while he was in the limelight. Marrying Salma, a shrewd and intelligent woman, helped Saeed excel in public relations and in subsequent business ventures. In no time, he was being considered one of the leading industrialists in Karachi. Salma herself was a prominent woman leader of the National Democratic Party and was given a ticket to contest the proposed elections in October 1977, which never took place.

On the twin tour of Australia and New Zealand in 1964–65, Saeed, despite his below-average form in the Test matches, was able to reach a thousand marks in fourteen first-class games. But it was his activities off the field that were catching the headlines. Being a vice captain, he could have set a better example, but instead, he turned into a very difficult individual. During the tour, his wife Salma joined him, despite the tour guidelines stating the contrary.

It was only the direct intervention of the then Finance Minister that stopped the tour manager, Mian Muhammad Saeed, from sending Saeed Ahmad back home. The highlight of another disappointing tour of England in 1967 was his two memorable knocks of 44 and 68 on a rain-soaked pitch in the second Test at Nottingham. By scoring 44.09% of his team’s dismal match aggregate of 24 runs. Saeed had established another nation that lasted for a long time.

The appointment of Saeed Ahmed as the captain of Pakistan for the MCC tour to Pakistan in 1968–69 was seen as political. In the first Test match at Lahore, Hanif Muhammad and Mushtaq Muhammad were doing their utmost to save Pakistan from defeat. A small section of the crowd booed the Muhammad brother, and it was believed that this demonstration was inspired by pro-Saeed elements.

The Lahore-Karachi rivalry filled many sports columns. It was also an open secret that Saeed had succeeded Hanif Muhammad as the country’s captain and was determined to hold the top post at any cost. With no shortage of self-doubt, Saeed was determined to cement his position by triggering anti-Hanif demonstrations. The Karachi crowd was not going to let Saeed get away with it when the two teams arrived for the third Test.

In the previous two Test matches, he’s produced very little bright cricket. The final test in Karachi, scheduled for a five-day duration, could have settled the series either way. But sadly, the game did not even survive three days as the stormy political scene of the city took over. On the first day of the Test match, the Karachi Press splashed the story, alleging that Saeed Ahmad had refused to be photographed with Hanif Muhammad the previous evening and that the tension between the two was harming the team’s performance. It was later revealed that Saeed had merely suggested obliging after a few moments rather than refusing to pose for photographs.

But he was left with no choice but to issue a statement in an attempt to defuse the uneasiness in the Pakistan camp. The statement issued to the press, which was countersigned by Hanif, My attention has been drawn to a news item alleging that I refused to pose for a photograph with Hanif Muhammad at a local function on March 5th.

This has come to me as a profound shock, and I have reason to believe that it is part of a campaign to create differences within the cricket team and to lower the prestige of cricket in our country. I issued a statement last evening categorically denying the report as baseless and malicious. In fact, Hanif Muhammad himself expressed to me his utter surprise at reading this news item.

At this point, I would like to refer to a speech made by me at a reception in my honor at the Hotel Intercontinental on the M.C.C. tour. It will be recalled that I paid tribute to Hanif Muhammad as the backbone of the Pakistan cricket team. I’m sure that he will be the first to endorse that I have, on every occasion, paid respect to him as a player of international repute. Moreover, I am proud to add that no amount of mischief-making will succeed in destroying the unity and solidarity of the Pakistan Cricket Team.

The statement above failed to serve its purpose, and Saeed came out with little credit in a series that was marred by political unrest. Saeed’s eventful cricket career took another twist when he was replaced by Intikhab Alam to lead against New Zealand on October 12, 1969. The selection committee, chaired by Saeed’s first captain, Abdul Hafeez Kardar, did not see him as the right candidate.

Shocked at his dismissal, Saeed’s fiery temper took over, and he was involved in an abusive slanging match with the selectors. The following day, it was announced by the board that Saeed had been debarred from playing first-class cricket in and outside Pakistan by the Executive Committee of BCCP.

In its emergency meeting, the board came to the conclusion that the former captain was responsible for gross misconduct and disorderly behavior soon after his announcement regarding the appointment of the new captain of the Pakistan Test team. In the press conference, Saeed received very little sympathy for his outburst and was painted as the chief villain in this episode.

The ban was lifted on October 26 after Saeed apologized for his irresponsible conduct. But he was not considered for the Test series against New Zealand. More drama was in store on the England tour of 1971, when Saeed Ahmad, not for the first time in his career, caught the sporting headlines for the wrong reasons.

His attitude on his third tour of England was mysterious, to say the least. Time and again, he would simply disappear without informing the tour management of his whereabouts. In the 18-man squad, Saeed was the senior-most player and was also a member of the tour selection committee. But right from the opening game against Worcestershire, Saeed was back to his old tricks.

Having served his country so well at number three positions for the last thirteen years, for some strange reasons he refused to take up the challenge on this important tour. However, he was to regret his decision as the twenty-three-year-old PIA batsman Zaheer Abbas made the most of this God-sent opportunity on his maiden tour, which left Saeed Ahmad with no place at all in the team.

It seemed that he had almost given up hope after failing to justify his place in the opening test at Birmingham. On the morning of the test, he left for London, saying that he needed medical treatment without detailing his injury or illness. It was later revealed that he spent the next six days with his wife, who was staying in London. For the second test at Lord’s, he was not to be seen for the first two days.

It was a deplorable attitude on behalf of a senior player and ex-captain. And when finally he was selected for the third Test at Leeds, the Chairman of the BCCP, Mr. I.A. Khan, held Saeed and Mushtaq Muhammad responsible for the tourists’ 25-run defeat. Saeed was cast in retrospect by Zakir Hussain Syed. Saeed Ahmad was hopelessly out of form and got himself out in all sorts of manners during the tour, being bowled by a full toss or pulling a long hop straight into the hands of the only fielder between midwicket and fine leg.

Even his traditional luck once betrayed him. His fielding was never an asset. Thus, his selection for the final test was primarily based on his being a tour selector. Any youngster would have been of more value to the side. To have asked him to lay under these circumstances and then expect a match-winning performance was asking a little too much. In some quarters, it was also rumored that Saeed Ahmad had deliberately not given his full support to captain Intikhab Alam on the tour. Deep down, he still grieved over his sacking two years ago and could not possibly see his successor achieving any glory.

With Saeed’s indifferent attitude on the England tour not in the distant past, Captain Intikhab Alam and co-selectors were not overly keen on his selection for the Australian tour. But he left them with no choice by scoring a hundred and taking six wickets in the final trials. In the first Test match at Adelaide, Saeed Ahmad was asked to open in the second inning when debutant Talat Ali had his right thumb fractured by a ball from Dennis Lillee.

Not to be overawed by the fiery West Australian, he managed to put on 88 with Sadiq Muhammad before he received a poor LBW verdict. After his gutsy knock, Saeed was promoted to the opening slot for the next Test in Melbourne. As luck would have it, it proved to be his last Test appearance for Pakistan. In the first inning, Saeed Ahmad was forced to retire after receiving a blow on his hand while trying to hook Dennis Lillee. He was later to return and take on Lillee to reach a well-deserved fifty. It was in the following couple of days prior to the final test that Saeed fell out with tour management.

The selectors wanted to continue to open the innings on what turned out to be a lively wicket. In the previous game, Saeed had exchanged verbal pleasantries with Lillee, and it was rumored that the incident had left the Pakistan batsman with very little heart. He declined to open the innings and asked the selector to put down the order where he had served the team in the past as he was not fully fit either. His explanation was taken by the selectors as a lame excuse, and after an ugly incident, he was declared sadly out of form and sent home.

It is to be noted that BCCP president Abdul Hafeez Kardar with whom Saeed never enjoyed good understanding, was accompanying the touring squad. Kardar’s presence did not prove a good omen, and when Saeed Ahmed refused to go back home, he was left stranded in Sydney while the rest of the team flew over to New Zealand.

Poor Saeed Ahmad paid a heavy price for confronting the ironman of Pakistan cricket. His international career was over as one of the country’s leading sportsmen was left penniless and without an air ticket. His political links with the Pakistan Sports Minister came in handy, who arranged Saeed’s flight back home. The Test career of Pakistan’s most controversial and temperamental cricketer had come to a sad end.

After returning from Australia, a life ban was imposed on Saeed for representing any team in domestic cricket. Although the ban was lifted by the kind intervention of the President of the Pakistan Sports Board, A.H. Peerzada, he was named to lead the Karachi Blues in the Patron’s Trophy in the 1973–74 domestic seasons.

But the old zest for the game had deserted him, and he decided to quit. He seemed more concerned with his rubber goods business in Karachi and with his effort to establish himself in the political scene of the country. All of a sudden, in 1977, at the age of 40, he came out of retirement and announced his availability for the Test series against Mike Brearley’s touring Pakistan. Kardar has resigned as BCCP President, and the country’s leading players have been signed up by Kerry Packer.

Saeed saw it as a good opportunity to come back into the limelight in view of his political ambitions. It was on the strength of his political links that he managed to be selected for the three-day game against the tourists in Peshawar. With no first-class cricket for almost five years, it surprised very few when he looked out of place in competitive cricket.

Throughout the sixties, Saeed was a regular face to be seen in English summers for his league cricket and business engagements. In 1965, he stole the limelight in the Lancashire League when his all-around success of 637 runs at 28.95 and 99 wickets at 8.92 helped Nelson win the championship by a record margin of 15 points.

In the same season, he also represented Littleborough in the Central Lancashire League. Wisden recorded Saeed’s all-around contribution. In addition to his splendid match returns, Ahmad also set a splendid example on the field in his encouragement of the junior players at Nelson. His own high standards continued the next summer, but Nelson finished 7th on the table.

Saeed Ahmad Brothers

Saeed’s half-brother, Younis Ahmad, represented Pakistan in four Test matches. Younis was a stylish left-handed batsman who was capped by three English counties, i.e., Surrey, Worcestershire, and Glamorgan, during a distinguished first-class career. In the early 1970s, he also represented South Australia for a season in the Sheffield Shield. Younis Ahmad received a life ban lifted later on as a result of touring South Africa with the Derek Robins team in the early ’70s.

Saeed Elder’s brother Nasir was not into cricket, but his younger brother Anwar Ahmed served on the MCC staff in the mid-seventies. While the two of his younger brothers, Nadeem Ahmad and Naveed Ahmed, have represented various English leagues, Pakistan’s leading bowler of the 1970s, Sarfraz Nawaz married Saeed’s younger sister.

Writing about Saeed Ahmed, perhaps the most controversial and misunderstood cricketer of his generation, is indeed a delicate task. It is very strange for a man of fiery character, as Saeed no doubt was, to not have spoken to the press at any great length for the last 30 years or so.