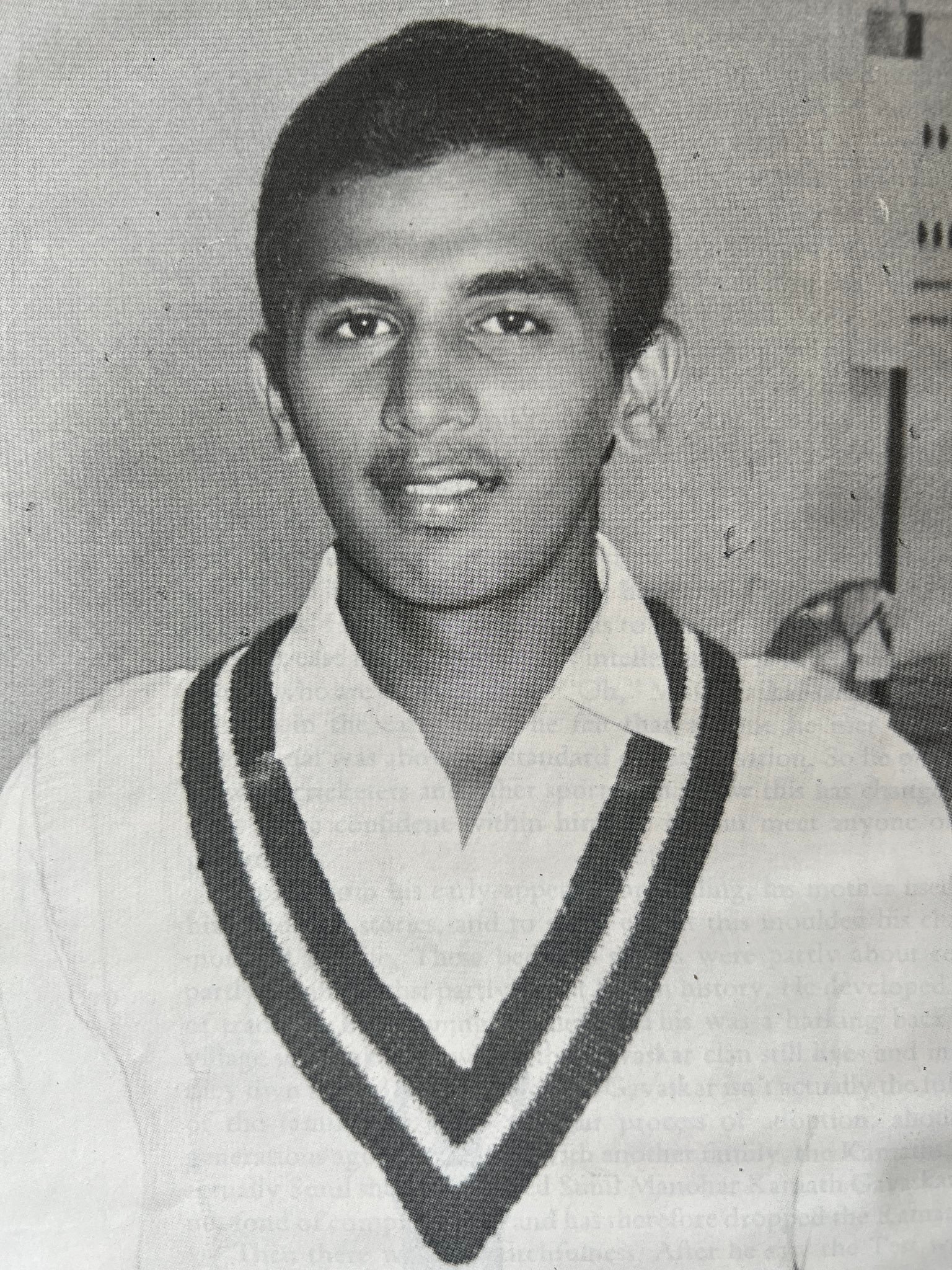

Sunil Gavaskar, at 21, became the first Indian to score over 700 runs in a Test series and the first-ever Test cricketer to score over 700 runs in his debut Test series. He is a star attraction of the Indian touring team, which plays its first match against Middlesex at Lord’s on June 23. I have learned a lesson. Henceforth, I shall only show my back to the bowler.’ So did Gavaskar write to a friend in Bombay during the Fourth Test at Barbados when Dowe’s hostile demeanor provoked him into playing an injudicious hook?

This was no vainglorious statement, but a plain declaration of his aim and purpose. It was as if Gavaskar had planned it all out with the same meticulous care with which he, as a student of economics, marshals his facts and figures. On the recent West Indies tour, Gavaskar made scores of 71, 82, and 32 not out; 116 and 64 not out; 0 and 67; 1 and 117; 14 and 12; 124 and 220. It was a remarkable achievement.

Not since Vijay Merchant and Vijay Hazare had an Indian batsman score so many runs and with such consistency. With Sunil Gavaskar, it seemed to be just a matter of habit, cultivated from his schooldays. This happy habit was first manifested in the season of 1965–66, when he made his debut for West Zone in the All-India Schools tournament with 246 not out against Central Zone. He followed this up with 222 against the East Zone and 85 in the final against the North Zone.

The same year, he made 40 for West Zone against the London schoolboys, with 11 in the Bombay ‘Test’ and 55 and 57 in the Delhi and Kanpur representative games. The transition from school to college cricket was equally successful. It marked a further stage in his development as an opening batsman of promise. For West Zone, he recorded 247 not out against South Zone, the highest ever in the Vizzy Trophy zonal championship for Indian universities.

He followed this with 113 not out in the second inning to enable the West Zone to make good on a slender first-inning deficit and snatch the title from the North Zone. This was in the season of 1968–69. Then, on the eve of the West Indies tour, he staked his claim for consideration among the seniors by recording a new high in university cricket, with 327 against South Gujarat. In recent times, universities have been regarded as the nurseries of Indian cricket.

It was apparent that there was an adequate replacement for the opening position left vacant by the engineer’s migration to England. Gavaskar, however, was not spoiled by success. He learned that cricket could be a game of ups and downs and that it could be hard going at the higher levels. After serving a two-year period among the reserves for Bombay, he failed in his debut against the Rest of India in the Irani Cup match of 1967–68, scoring only five and zero on a lively wicket.

His first inning in the Ranji Trophy was equally undistinguished. He was lbw for a duck. But given another chance by the far-sighted selectors, he came back with 114 and shared in a Ranji Trophy record first-wicket stand of 279 with Ashok Mankad. The following season, with the West Indies tour in the offing, he drew the attention of the national selectors to his ability as an opening batsman with knocks of 104 and 176 in the Ranji Trophy.

When Sunil Gavaskar was included in the team to tour the West Indies, it was assumed that he would be the reserve opening batsman and an understudy to Mankad and Jayantilal. A whitlow on his finger, aggravated by a tendency to bite his fingernails, kept him out of the early games. But the moment he took his stance in the first big match of the tour, it was apparent that Indian cricket had found the opening batsman it had been looking for these many years. In his first Test match, Sunil Gavaskar had the luck that goes with the young and the brave. He was dropped early in his innings by Gary Sobers, of all fielders.

He went on to score 65 and help India build a match-winning lead. In the second Test at Guyana, he was dropped again at slip by Gary Sobers off Shillingford. Then, at only six, he went on to make 116—the first in a sequence of scores that was to earn him a place in the record books at the end of the series. Those two chances seemed to be due to some lapse of memory, for in the practice sessions before the West Indies tour, Sunil Gavaskar had repeatedly been advised to refrain from sparring at the outgoing ball.

He was wiser for this experience, for in the long innings that he played at Barbados and in the final Test at Port of Spain, he refrained from making exploratory passes at the offside ball. In view of Gavaskar’s remarkable achievements, it may well be asked what kind of batsman he is. His tall scores are apt to give one the impression that he is a lively, venturesome batsman. This would not be a strictly accurate picture.

Sunil Gavaskar is not the gay cavalier that Farokh Engineer is; he is also not one of our ‘dull dogs, who visited England in 1959. He is the sort of batsman who is likely to be appreciated in Yorkshire, no less than in Kent. No doubt, Sunil Gavaskar has the patience and imperturbable temperament beloved by northern countrymen. He showed it as he batted through nine hours to save the fifth Test for India.

Sunil Gavaskar also has a thumping square drive and the ability and willingness to advance on quick feet to attack the spinners, which should please the discerning follower of cricket. All the world, so it seems, loves a star batsman. And when it happens to be someone like Sunil Gavaskar, who looks like a schoolboy with his sunny smile, just out of school, one can well understand the adulation and the praise that have been showered on him.

Read More: The Day G.R. Vishwanath Wept