The curtain fell on the Reliance World Cup It was time to salute a retiring hero whose final game was played in an urgent rush. Sunil Gavaskar has never been a run machine. Despite those 10,000 Test runs, he did not want things to go too smoothly. Something in his spirit recoiled at the regularity of churning out nuns.

He’d tease the crowd in one-day internationals and enchant them the next. In 1975, he grafted to boring 36 not out in a 60-over game at Lord’s by way of idle protest. In the 1987 World Cup, he followed an infuriatingly timid inning against Zimbabwe with an astonishing hundred against New Zealand.

As captain, he could slow the game down, adopting tactics barely within the rules—as he did when India bowled nine overs in an hour against Fletcher’s England side. Off the field, he’d “chuckle,” and so people forgave him. Yet he never stilled this streak of non-conformity, which could rarely find its expression in his batting.

Maybe if he’d been a few inches taller, he’d have been a swashbuckler. It used to frustrate him that he couldn’t slog because he believed that prevented him from tearing into attacks in the manner of Viv Richards or Clive Lloyd. If his effort against New Zealand was anything to go by, he corrected this weakness at the end of his career. Sunil Gavaskar created for himself a character he could enjoy, as if it compensated for his ruthlessness on the field.

It amused him to appear hopelessly impractical. In 1980, at Somerset, he could scarcely boil water, and once he was found in a telephone kiosk, trapped by dogs, of which his fear is well documented and (given the incidence of rabies in India) well-founded. If Gavaskar saw a dog on the field, he’d invariably lose his wicket. It was a fatalism he adopted to protect himself from the apparent infallibility of his work at the wicket.

In the dressing room, he’d pass dry comments, observing that our bowling wasn’t quite as good as theirs and asking if Rose—who was in a particularly exuberant patch that season—always batted in this way. Later, he blamed his experience in that damp summer for a loss of commitment on the grounds that Somerset players didn’t worry if they failed or if the team lost (which wasn’t quite the case—that he thought we didn’t mind showed how much he’d minded previously).

Sunil Gavaskar thought this sense of perspective had undermined his singularity of purpose. He was certainly amusing company, understating his character to counterpoint Botham’s effusions. His colleagues were charmed, but not fooled. This was a tough man, a determined man who didn’t drink or smoke, who rose at dawn, sipped ginseng tea, and led his life with modesty. We realized he wanted to score runs, but he did not want to die a run-scorer.

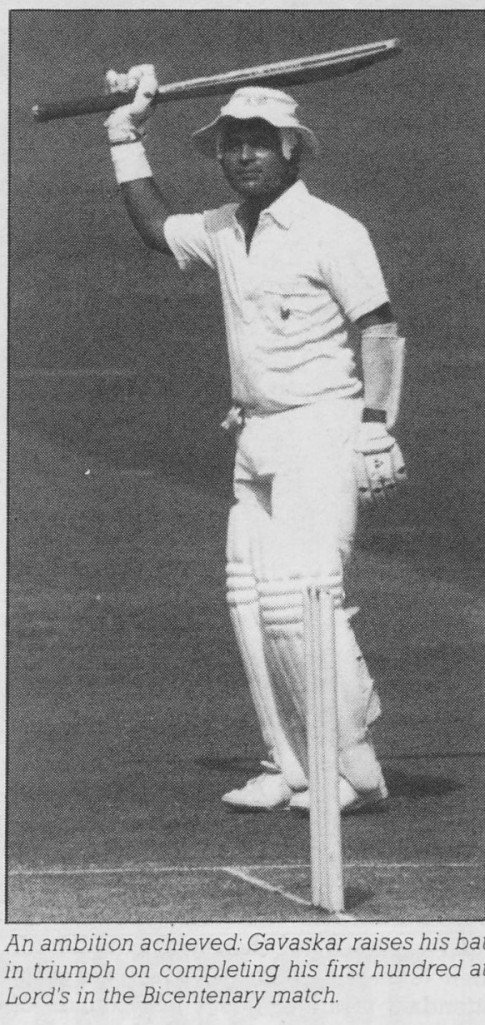

For all this chuckling humor, Gavaskar’s dedication could not be mistaken. He was out for a duck a few days before the bicentenary game at Lord’s, a ground on which he’d never previously hit a hundred. He spent the next three hours practicing his backlift in front of a mirror in order to eliminate a weakness he’d detected.

This after he’d scored 34 Test centuries. Of course, he hit 188 runs in that farewell appearance. His hallmarks as a batsman were his attention to detail and meticulous preparation. Denied power and stature, his game depended on precision. He could not afford to make mistakes to the crease Gavaskar could summon BA: the ferocity of effort rivaled in my experience only by Viv Richards and Martin Crowe.

If his mind began to wander, he’d hood his eyes, focusing them upon the batting strip, eliminating everything else, for this was an empire and he was the emperor. He never looked at the scoreboard or the clock, considering them to be irrelevant. In this power, to the tunnel, his concentration lay the secret of his greatness. It was a single-mindedness against which his puckish and irrelevant temperament was occasionally allowed to rebel. Not often, but occasionally.

In his retirement from international cricket, Gavaskar will be a considerable star. Already, he runs a sports manufacturer, and a sports agency, is a marketing executive, writes books and articles, and appears as a model on television, advocating the merits of particular brands of toothpaste, hair dye, aftershave, and footwear.

His image is that of a smart, sophisticated, and yet humble man. One of the wonders of the world is the way in which Sunil Gavaskar’s hair has gone from grey to black. Usually, these things occur only in Scunthorpe. Some people resent the way in which Sunil Gavaskar and other Indian stars appear in advertisements, for Florence Nightingale’s spirit is supposed to prevail in cricket.

In fact, of course, the World Cup itself was not much more than an advertising campaign for cricket, and as such, it was a resounding success. In the torrent of rupees, only a remarkably monkish cricketer could be counted on to be abstinent. In the first 12 pages of November’s India Today, a political magazine, there were five full-page advertisements. Featured models were the Nawab of Pataudi, Sunil Gavaskar (twice), Ravi Shastri, and Kapil Dev.

Throughout the subcontinent, cricketers are heroes. Two recently departed Test players, Sandeep Patil and Mohsin Khan, are famous film stars. Nearly every other cricketer still in the game is using his name in one way or another. It is churlish to criticize Gavaskar’s typically methodical approach to his business career.

He has a reputation for reliability and practicality. Businessmen say he is neither spoilt nor greedy. Though effectively Maharajah of Bombay, he has lived in the same ordinary flat and has driven the same old car throughout his career. His hair might have changed color, but his head has not been turned. His son is named after Rohan Kanhai.

Gavaskar is to be respected for building this second career. In doing so, he is expressing the Bradman side of his character. Upon his retirement, Bradman entered the Stock Exchange and became a hugely successful entrepreneur. Gavaskar will do well but he will never lose the whimsical side of his character, or his profound interest in mysticism. Just before the World Cup, he went with Kapil Dev and Dilip Vengsarkar to visit his Hindu holy man, Sai Baba.

This is not oriental superstition but a serious belief that strengthens and nourishes him. Gavaskar’s faith gives him a calmness and a fatalism he has found helpful during his career. It is important to believe in something when 900 million Indians are relying upon you. In a land of hawkers and hustlers, Gavaskar remains a mild, temperate, and subtle individual.

Read More: Sunil Gavaskar Goes On – Solkar Goes

He lives with those traders who earn their rupees in the streets but from time to time he calls upon his mountain holy man. His life, like his batting, is a mixture of modest if driving ambition and a quixotic romanticism that lends it a touch of the mystical East.

He is retiring at the right time, when they are asking why rather than why not. He has been a master craftsman with the temperament of an artist, a grafter whose orthodoxy was so precise as to be defined as a genius. Great cricketers are distinguished by the regularity with which they play at their best and by the way in which they can dictate the game. Sunil Gavaskar could do both. It wasn’t just the Bicentenary game.

Sunil Gavaskar scored hundreds in Sydney and in Melbourne two years earlier, those being the only Australian Test grounds upon which he’d never previously reached three figures. And then there was that wonderful inning against New Zealand. He’d set his heart on one final goal. He wanted, before he retired, to hit a century in a one-day international. It took him 85 balls to do it. Cricket can thank Gavaskar for his immense contribution. To a connoisseur, no joy could be finer than to watch Bedi or Hadlee bowling to him. May his new career be as sweet.