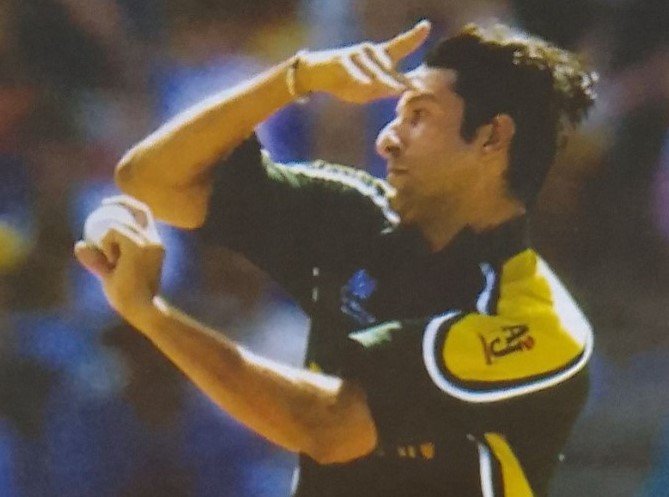

Sambit Bal had an interview with Wasim Akram in 2004

Q: This knowledge of how to use the conditions, having so many tricks up your sleeve, how much of it came from learning to bowl in Pakistan, where the new ball did nothing?

There is no way you can depend on wickets in that part of the world, especially at the Test level. As a fast bowler, you have to learn variety. If the new ball didn’t work, you had to get the slower balls going; you had to mix them up; and with the old ball, you had to learn how to reverse.

Imran Khan was my teacher, which allowed me to make the best use of the conditions, to practice hard and to remain patient, and to develop my mental game as a fast bowler. He taught me that you have to be hungry in order to succeed. He also taught me to never give up and to never be satisfied.

Q: How did you manage to master so many different balls? How much of it came naturally?

I was a natural swing bowler. I could swing it from left to right, but then I realized that I had to expand my skills. I learned a lot of it by myself in the nets. I developed the slow ball in 1991. Franklyn Stephenson took lots of wickets in county cricket with a slow ball that no one could pick, and I decided I had to learn to bowl it.

I spoke to a lot of people, including Malcolm Marshall and Richard Hadlee, and then went to the nets and worked on it. I learned two variations of it, one coming into the right-hander and one going away.

Q: You also took a very unusual action. When you used your quick arm action during a run-up, you could generate quite a bit of speed.

That was God’s gift. Nowadays, you see bowlers like Muhammad Sami and Ajit Agarkar; they all have a quick arm action, which makes the ball skid on. It’s a blessing. Batsmen from all over the world used to tell me that they could never pick my pace. Even though I was not lightning quick in the air, the ball used to hurry onto the batsman off the pitch. That’s how I got a lot of my wickets.

Q: You also use a lot of your wrists.

Swinging deliveries is all about using the wrist. In seam bowling, you need to hit the seam consistently, but there is no seam movement on most Indian and Pakistani wickets. So you have to use your wrists and learn to swing. The outswing was one of the skills I learned when I bowled in the nets in Australia in 1989–90. It took me two weeks to get the confidence to bowl it in a match. In the next Test, I took four wickets with an outswing.

The nets seem boring to a lot of people, but I enjoy bowling in the nets. I would try all sorts of things: go around the wicket, bowl wide of the crease, go close to the wicket, and try many variations. If you want to be a good fast bowler, you have to be prepared to work very hard. Swing-bowling is a science.

It can be learned quite easily, I would say, if one is willing to apply his mind and is prepared to practice for long hours. And then it depends on how you adapt to the conditions and how you learn to look after the cricket ball itself.

Q: Why is swing bowling a declining art? You were easily the last of the great swing bowlers in world cricket.

In a conversation with Alan Davidson yesterday, I was asked the same question: Where have the swing bowlers gone? You have hardly seen the ball swing in this series. It seems that bowlers are no longer taught how to swing the ball; they are asked to bowl fast instead. Any young bowler reading this should learn how to swing the ball if they want to take wickets in international cricket. Pace alone doesn’t get wickets at this level. Swing is something that can be learned.

Q: Do you think that one-day cricket bowlers are discouraged from swing bowling because of the length of time they are expected to bowl?

That is a factor. You might get some freedom with the new ball, but after a few overs, it’s wicket-to-wicket and on a length. You can’t do anything else. Discipline and line length are the keys after that.