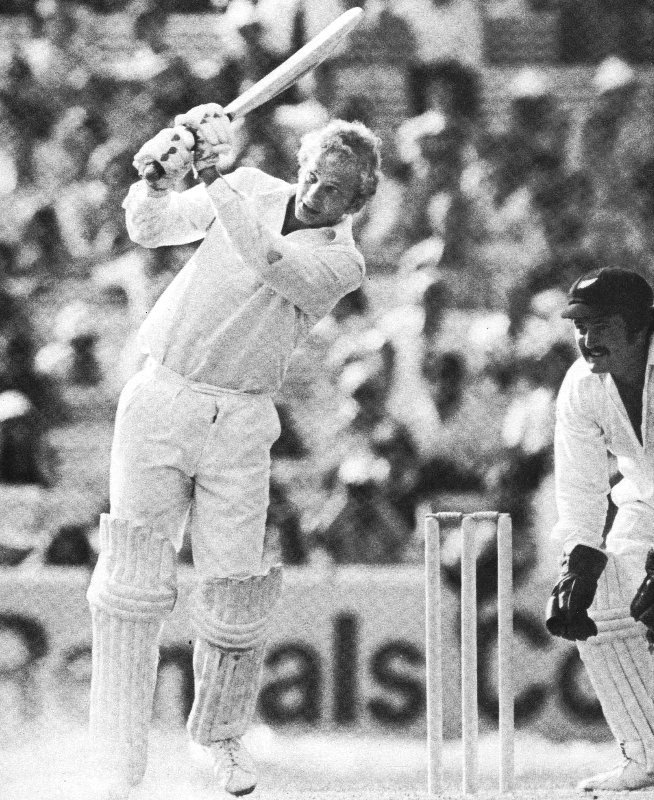

Of all the many strokes I have seen played during 1978, the three that I shall remember the longest came from the bat of David Gower. The 1978 summer in England may have been one of the wettest on record, but it will be remembered longer as the summer that saw the emergence at the highest level of this brilliant young batsman. On Friday, June 2, soon after lunch, David Gower came out of the pavilion at Edgbaston to play his first Test innings, with England scoring 101 for two.

Mike Brearley had been run out, and David Gower had to wait for his first ball. These were two or three minutes, which would have created butterflies in the hardest of stomachs. David Gower has that thoroughbred walk that marks him as an athlete of distinction before the pavilion gate is ten yards behind him. He took the guard, cap-less and outwardly relaxed, and looked around the field before settling into that tidy, classical left-handed stance. Liaquat Ali, fast medium left arm over the wicket, began his slanting run from the press box end.

Just before all reached the crease, David Gower gave two modest taps of the bat against his left toe. The ball came down; it was short, pitching may be on the line of the middle stump, with the angle of delivery going across David Gower to the leg side. He saw the ball early with precise, unfussy footwork, moved outside the line, and hooked. The bat made that satisfying resonant sound as it struck the ball, and their long leg could only jog around to his right to retrieve it after it had crashed into the fencing in front of the Rae Bank stand.

It was the most conclusive and emphatic entry into Test cricket that any batsman could ever have made. That stroke and the preamble leading up to it admirably summed up the ability, temperament, and approach of David Gower, who is still only 21 and yet already a batsman. Anyone in the world would be glad to come and watch. For one who saw England’s batsmen plod their way through Pakistan and New Zealand last winter, Gower’s success has come as a welcome relief.

For those apprehensive that equally dull batting by England in Australia this coming winter will cause spectators to depart in their thousands to Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, his emergence is wonderfully reassuring. One’s first impression of David Gower comes from his sociable smile and the frank and completely unaffected way in which he talks. His somewhat crimpy fair hair helps exaggerate his boyishness, while his conversation reveals an unexpected maturity. He has the slight, angular figure of a fine athlete. When he walks, his feet appear hard enough to bruise the grass.

When he runs between the wickets, which he does deceptively fast, he seems to be floating over the surface. David Gower comes from a sporting family. His father won a hockey blue at Cambridge but did not live to see his son’s triumphs on the cricket field. David was born in Kent, went to Africa when his father worked there, and returned to be educated at King’s School Canterbury. When his family returned to England, they settled in Loughborough, hence his Leicestershire connections.

Just how good a batsman is he, and what marks him as different from the rest? He is unquestionably a batsman of the highest class, although one cannot yet be certain how far he will go. The second part of the question is equally easy to answer, for a ten-minute glimpse of him at the wicket reveals all the hallmarks of true class. Or, if one was lucky enough to see it, that first stroke in Test cricket provided an answer that was just as decisive. A lot of young batsmen have been crucified by being depicted after their first two centuries as the new Compton or the new Bradman, and excessive adulation at the start of anyone’s career can be a dangerous burden for them to live with.

Since the moment he came onto the Leicestershire side, he has been talked about as a future England cricketer. In 1976, he made 88 not out against the West Indies at Grace Road, whereupon Illingworth declared and David Gower was happy to accept his captain’s decision and the reasons for it, although the game ended in a dull draw. In 1977, he opened the inning for much of the season and continually got himself out, going for his strokes with a delightful and yet naïve innocence. He was more successful towards the end of the season and might reasonably have been picked for the tour of Pakistan and New Zealand.

But Ray Illingworth felt that he was not ready. Instead, he went to Perth in Western Australia and played a season’s Pennant cricket with ever-increasing success after a poor first few games. He worked out the mysteries of Australian pitches, learned to cope with the steeper bounce, and realized the importance of being able to play off the back foot. Most important of all, he learned responsibility in his cricket and returned to England a more mature player.

He may have been fortunate to start his Test career against two relatively weak sides, and it would be foolish to suggest that he will not have to combat failure at some future date. If this winter he fails in the first two Test matches, he will come out at the Melbourne Cricket Ground over the New Year with pressures upon him that he has not so far experienced. This will be a supreme test, but I believe he has the temperament and the ability to come through that and any other hypothetical crises.

I believe, too, that wherever he plays, people will be queuing to buy tickets to watch him bat, for he is that sort of player. They will take pleasure in his fielding in the covers, and those who are lucky enough to meet him at receptions or parties will go home saying what a charming and unassuming chap he is. And those other two strokes: in the Third Test against New Zealand at Lord’s with one over to go on the second day, Gower faced Richard Hadlee, needing four for his fifty. Most batsmen would have been thinking longingly of the pavilion and tomorrow.

Richard Hadlee was bowling fast. His third ball was up to the bat, if not quite a half-volley and outside the off stump. With a cover drive that was easy, elegant and perfect in every detail, Gower dispatched the ball to the Tavern rails. England began their second innings in the same match needing 118 to win and soon they were 14 for two after Richard Hadlee bowled Geoff Boycott and Clive Radley with successive balls. Another wicket now and England might even have lost.

David Gower pushed easily forward to the hat-trick ball and three over’s later, Collinge faced. A short one came down pitching on the off stump. Gower’s feet took him across in a split second and the ball was pitched among the crowd in front of the Tavern Bar. I would have traveled miles at great expense to see any of these strokes, but anyone who has seen Gower play an inning of any length will know exactly what I am talking about.