In the select group of contemporary Test wicketkeepers, Deryck Murray is something of an odd man out. He is the straightest man among the several extroverts. He is outshoned by the raucous enthusiasm of Rodney Marsh, the spectacular impishness of Farokh Engineer, the energetic brilliance of Alan Knott or the unorthodox contortions of Wasim Bari. He lacks what is known in show business as razzamatazz. He just wasn’t cut out for the stage.

On the field and off it, he is quiet and unfussy, dedicated to doing his job with calm efficiency. The Marshes, the Engineers, and the Knotts (and so many other great ‘keepers before them) are the type who need to keep in the game all the time to maintain themselves at full pitch, and burn off nervous energy. Deyrck Murray (and others of his ilk) are the complete opposite. Unfortunately, the wicketkeeper who does not make a habit of diving and tumbling all over the place or whipping off the bails at every given opportunity tends to be taken very much for granted and, very often, underrated.

So it has been for Deryck Murray, despite the fact that there has been no more consistently successful wicketkeeper-batsman in West Indies Test cricket. In 41 Tests (up to the second of the current series), Murray had scored 1311 runs and claimed 124 victims (117 caught and seven stumped). No other West Indian has achieved such a test double. His selection for the tour of England in 1963 was as much a surprise to him as anyone else, and it was a choice of simple expediency.

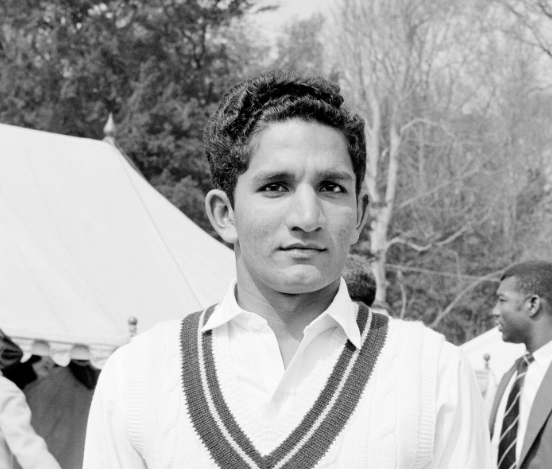

In the 1962 series against India, Jackie Hendriks of Jamaica was the No. 1 wicketkeeper before he broke a finger, after which David Allan (Barbados) and Ivor Mendonca (Guyana) were alternately used as replacements. As it turned out, Jackie Hendriks was living overseas and was unavailable for the England tour, Ivor Mendonca had fallen from favor for some misdemeanor; and, since the Windward and Leeward Islands were not then recognized as first-class entities, the field was down to David Allan, as No. 1, and Murray, 20 years old and just out of Queen’s Royal College, Port of Spain. It is not to say that Deryck Murray came in starry-eyed and unprepared.

Deryck Murray was born into a family with rich cricket traditions. His father, Lance, played for Trinidad as a leg-spinner and, for many years, has been a leading administrator, on both the Trinidad and West Indies Boards. His uncle, Sonny, is a long-standing secretary of the famous Queen’s Park Club. He attended the school, which, at the time, had the old Surrey pro, Tom Clark, as a coach and which, over the years, had produced Test players such as the Grant brothers (Rolf and Jackie), the Stollmeyer brothers (Victor and Jeffrey), Gerry Gomez, and Prior Jones.

He had watched Test cricket at the Queen’s Park Oval, less than a mile from his home, since he was a boy. He had played first-class cricket two years earlier, for Trinidad against E. W. Swanton’s XI. Even so, his maturity and sure-handedness in 1963 were phenomenal for an inexperienced youth. He immediately won the confidence of his captain, Sir Frank Worrell, who had no hesitation in giving him a Test place on the evidence of form and a slight fitness doubt over Allan.

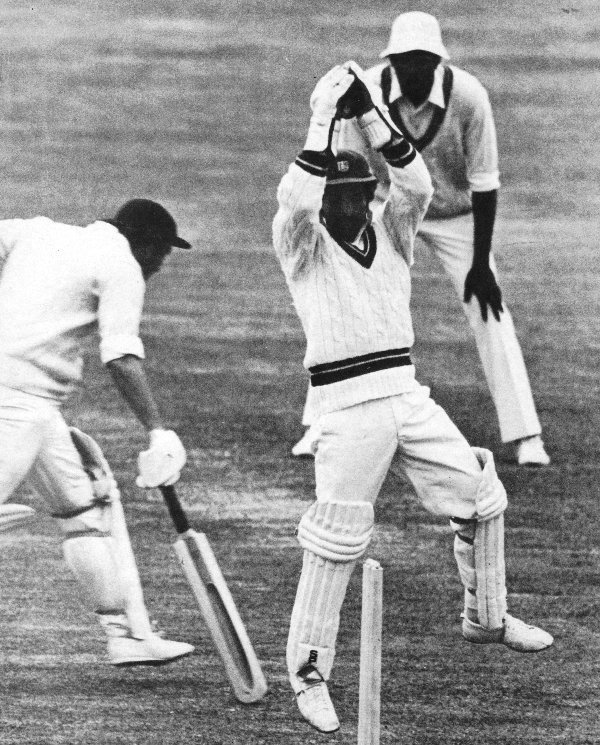

He played in all five tests and set a new record. It is always easier to stand back than to stand over the stumps, and Murray’s accomplishments have been unfairly dismissed in some quarters as being straightforward since the West Indies attack was dominated by pace. Yet there was the bowling of great speed and hostility from Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Gary Sobers, and, significantly, Lance Gibbs also played a crucial part, particularly in the first Test.

Deryck Murray may not have flung himself full length to hold many snicks. It was not his manner then and has never been since, although this is not to say that he never does. His secret is anticipation and advice given to him on that first tour by Worrell to move the off-side foot first when going for a leg-side take. For most 20-year-old West Indians with such a start, Murray’s path would have been predictable. He was an exception County cricket did not become a widely attractive profession for the overseas player until much later, and young Murray had to think of a career first.

He entered Jesus College, Cambridge, in 1964 to study for a degree in economics and, although he continued cricket at university, gaining his Blues in 1965 and 1966 (the final year as captain), he had to sacrifice his Test place. Jackie Hendriks came back into the team for the 1965 series against Australia and he and Allan were on the 1966 tour to England. By then, Murray had been around the county circuit long enough to convince himself that this would be his life. As a Cambridge undergraduate, he joined Notts under special registration in 1966 and was qualified for them by residence in 1968.

In 1966–67, Deryck Murray returned to the West Indies team for the short tour to India (as No. 2 to Jackie Hendriks) and, a year later, played all five Tests against Colin Cowdrey’s England team in the Caribbean (when Jackie Hendriks was unavailable). He did not have a happy time. His glove work was often sloppy and he looked only a shadow of the ‘keeper he had been when he left home five years earlier. Yet it was a shock when the selectors omitted him entirely from the party which toured Australia and New Zealand the following winter.

It was a decision that shaped his future career. He had failed to complete his degree at Cambridge but now entered Nottingham University, took three seasons off cricket (except for a break to play twice in the 1970 Rest of the World series against England), and obtained a master’s in business administration. His studies meant that he missed the 1971 series against India and the 1972 series against New Zealand.

When he did return to the Caribbean in 1973, Mike Findlay was the incumbent and was chosen for the first Test against Australia. With Murray challenging for his place, Findlay had a poor match and was dropped. Deyrck Murray replaced him and, since then, has played 31 consecutive Tests, consistently proving his great worth. His Test batting average— just over 22— is unflattering but a quick glance through the records will reveal how he has repeatedly saved lost causes.

In Australia, against Dennis Lillee, Jeff Thomson, and Gary Gilmour, he chose uncharacteristic methods of counter-attack, which proved highly effective In the dressing room, he has been the prime mover in the organization and formation of the West Indies Players Association. He is not a militant trade unionist but realizes that West Indian cricketers are very attractive international sportsmen whose interests need to be looked after.

Like all other cricketers, Deryck Murray finds it difficult to relate the vast crowds which attend Tests at Melbourne, at Lord’s, or at Calcutta to the pay that the 22 men in the middle receive. Deryck Murray wants to ensure that the money in the game is more equitably distributed. He is keen to see to it that sponsorship is not spoiled, that insurance schemes and benefit funds are provided for all players, and that the game in the Caribbean is well organized. The players, he believes, can be involved in all aspects of cricket— not just the playing.