India vs Pakistan Test Series 1960-61: Pakistan, who won the toss and batted first in four of the five drawn Tests, scored 2,481 runs for 68 wickets in 1,101.5 overs at a rate of 2.25 runs per over. India, who had first use of the wicket in only the last Test, scored 2,178 runs off 1,014 overs at an average of 2.14. The difference is virtually negligible, but Pakistan, on four occasions, set the tempo.

Furthermore, while they scored 140 for 3, 146 for 3 declared, and 59 for no loss in the second innings of the Kanpur, Calcutta, and Madras Tests, respectively, they were completely safe from defeat and were able to bat without a care in the world. In only two Tests, did India get the second innings? In Calcutta, they were in peril of losing the game when they batted a second time, and in the final Test, they went in when only ten minutes remained on the last day.

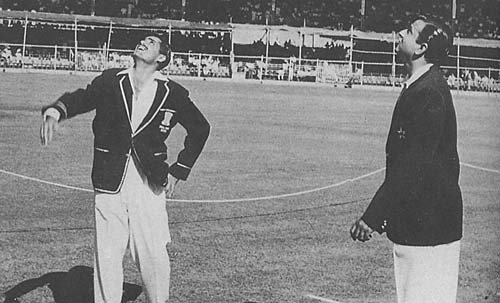

In the first four Tests, one was tempted to condone India‘s rate of scoring because Pakistan took about two days to put up totals of between 300 and 350, and then it was not worth India’s while to take risks and try and force a result in the remaining three days. But when it came to the Nari Contractor’s turn to call the tune in the last Test on an unimpeachable wicket at Delhi, his outlook was no different from that of his rival. Just over a full day’s play was lost in the whole series.

Rain took away four and a half hours from the third Test at Calcutta (now Kolkata); the fourth day’s play in the Madras (now Chennai) Test was curtailed by 20 minutes due to a fire breaking out in a section of the stands; and the start of the final Test was delayed by an hour. After accounting for Pose Batted, who won the toss these curtailments, the two teams aggregated 4,669 runs for an average scoring rate of 194.54 runs per day (of five hours) and 38.85 runs per hour.

The 200-mark was topped on only 11 of the 24 days, and on half of these occasions, it was on the last day when a decisive result was out of the question. But Pakistan must get credit for the highest number scored in a day. Ironically enough, it was on the opening day of the first Test that they made 241 for 1, with Hanif Muhammad batting in all his glory for the only time in his nine innings.

The lowest mark was reached by India on the third day of the second Test, when they put on no more than 149. India, though, was the superior side, and it was dropping catches at crucial stages that prevented them from winning the Bombay Test. The Indian team made three changes to the squad after the First Test: Pankaj Roy, Nana Joshi, and Ajit Wadekar were dropped, and wicketkeepers Naren Tamhane, V. M. Muddiah, and Saleem Durani were included. However, the Pakistani team included senior batsman Alimuddin.

At Delhi, it was through chances for all three batsmen who made sizeable scores that India built up a huge total, and they literally let the match slip out of their fingers, dropping no less than five catches. At Bombay, in the first Test, Pakistan was 300 for 1 at one stage. Then followed a collapse that was a virtual landslide, and they were all out for 350. The fear of a recurrence of such a debacle and Hanif Mohamed’s loss of form after his magnificent century must have detracted considerably from their confidence, although Saeed Ahmed did more than take over the role of sheet-anchor of their batting.

As the series progressed, the middle of Pakistan’s batting became increasingly reliable, but rarely did it exude the air of mastery. The only batsman on the Pakistan side who batted always with the demeanor of one in command was Saeed Ahmed. Imtiaz Ahmed, who opened with Hanif Muhammad, accumulated 375 runs for an average of 41.60, including a hectic century—at least the latter part of it was—at Madras, but none of his big innings were free of chances. India replaces Abbas Ali Baig, Subhash Gupte, and Bapu Nadkarni with Baloo Gupte and Datta Gaekwad after the third Test match.

At number four in the batting order, Javed Burki looked like a cultured cricketer. He did not come off in the first Test because he joined the team only a couple of days before the game, having stayed back in Pakistan to appear for a public service examination. But scoring 79 and 48 not out, he provided a backbone for both the Pakistan innings at Kanpur and in Calcutta; he twice topped the 40 mark.

He played no small part in saving the final test, scoring a valiant 61 in the first inning. Half of this inning was played practically one-handed because he had been badly injured. Javed Burki could barely grip the bat in the second, but he kept the ball out of the clutches of five or six close fielders for 45 full minutes and aided Mushtaq Muhammad in halting a collapse.

Mushtaq Muhammad, at number six, proved as resourceful as Burki, more so when things were going against his side. At the start of the tour, he looked like a ‘rabbit’ for leg-spinners, but he dealt with them competently by stretching fully forward to smother the spin. For a small man, he drove with force on either side of the wicket and hooked and pulled without fear.

He was struck more than once in trying to hook Desai’s kicking deliveries, but it never stopped him from getting behind the line of the ball; his century, which snatched victory out of India’s grasp at Delhi, was a valiant effort. He did not make many runs in the second inning, but without his long vigil, it might have again folded up quickly. The tail-enders all took their turns to rise to the occasion.

At Kanpur, Nasim-ul-Ghani, the Pakistanis’ only left-hander, played an invaluable inning of 70, a real lifesaver. At Calcutta, the hard-driving Intikhab Alam made 56 and enabled Pakistan to touch a respectable mark in the first inning. At Madras, the only Test in which Pakistan declared their first innings, no wagging of the tail was called for, and at Delhi, Mahmood Hussain frustrated India’s hopes of a victory.

Pakistan had a varied attack, but not one with the potential to run through the Indian batting. In a team of 17—too large a compliment for so short a tour—they brought out three: fast-medium bowlers, Mahmood Hussain, Muhammad Farooq, who had never played for Pakistan before, and Muhammad Munaf, described before the team arrived as the quickest bowler on the other side of the border. Then Fazal Mahmood came, now bowling with a shortened run and a lower arm, at just about medium pace.

Among the spinners were off-spinner Haseeb Ahsan and left-arm Nasim-ul-Ghani, both finds of the tour to the West Indies in early 1958. Leg spin was served up by the stocky, swarthy all-rounder Intikhab Alam, who, with Richie Benaud as his model, turned out to be a better leg spinner than we expected.

The terrors of Pakistan’s new ball attack were obviously on the wane. Mahmood Hussain had lost much of the speed and lift he had when he came here eight years earlier. Before the tour had advanced very far, the other two pace bowlers, Muhammad Farooq and Munaf, went on the invalid list, and Hussain had a lot of work to do.

Fazal Mahmood pulled a muscle in the opening game of the tour, an injury that recurred in the match prior to the first Test, and again in the first Test, As a run saver he was effective, bowling steadily at just short of a length, but only the softie’s green wicket at Calcutta gave him the look of a match-winning bowler.

This was one test—he captured 5 for 26—in which he was a menace. In the first Test, Mahmood Hussain and Fazal Muhammad were supported by Muhammad Farooq, who took 4 for 139 in 46 overs. But he got his first three wickets—those of Pankaj Roy, Abbas Ali Baig, and Nari Contractor—without much cost.

An injured muscle after this Test allowed him only two smaller games, but he returned to the side in the fifth Test and once more bowled effectively, bringing the ball in nicely off the wicket. A bowler with a run-up reminiscent of Ray Lindwall, Muhammad Farooq, at the age of 22, is Pakistan’s young bowler of the future, provided, of course. He trains up his muscles to withstand the strain and hard work. Contractor and Roy opened for India in the first Test.

If Pankaj Roy did not play again in the series, it was because of his unsure fielding and not because he was not impressive while making 23 runs out of an opening stand of 56. The Nari Contractor, who aggregated 319 runs for an average of 53.17, was consistently personified, and contrary to the fears of many, his batting remained unaffected by the onus of captaincy.

Pankaj Roy was replaced by M.L Jaisimha, who made a laborious 99 in almost eight hours in the Kanpur Test and remained the Contractor’s opening partner for the rest of the series. He never made another big score in four more innings, but he always stayed till the shine was off. Never did he look anything but a batsman of Test match class.

M.L. Jaisimha, however, does not enjoy opening the innings because it stifles his stroke play, which is as brilliant as that of any contemporary Indian batsman. Nothing was more unfortunate from the Indian angle than Abbas Ali Baig’s failure to get going. In contrast to his teammates, the little Oxford batsman sought runs from the very moment he arrived at the crease.

He did not play even a full over at Bombay, but at Kanpur, he seemed to be seeing the ball very well and provided a few moments of delightful cricket while making 13. At Calcutta, he started shakily against the spinners and was just settling down when he made an ill-advised pull and was bowled.

The faultless technique of Vijay Manjrekar returned to the side for the first time since his knee gave way during the tour of England. Their faultless technique makes him a sound and solid batsman in spite of his cap-less knee, but his stroke play has certainly been affected. Against Pakistan, he played his drives as handsomely as he always did, but less frequently. Polly Umrigar had a most successful series, with his six innings yielding 382 runs, including three centuries.

Chandu Borde always batted in a cavalier fashion, and he invariably changed the complexion of these innings. He failed at Kanpur after a handsome inning of 41 at Bombay, and the selectors wanted his head. Had Milkha Singh not reported ill on the morning of the match, Borde would not have played at Calcutta, where he saved India with innings of 44 and 23 not out. Haseeb Ahsan at Madras was threatening to mow down India for a paltry score after Pakistan had put up 448 for 8 and declared their highest total of the series.

Chandu Borde played the longest innings of his career, 177 not out, which again proved him the man for a crisis. He played another useful inning at Delhi, but this time his touch was unsure. As I have said earlier, India played Surendra Nath in only two Tests, trying to make do with either Rusi Surti or Umrigar as the other opening bowler.

A great burden, therefore, fell on Tiny’ Desai, and bowling 215.5 over’s, more than any other Indian bowler, he captured 21 wickets at an average of 29.76! Saeed Ahmad scored 460, Hanif Muhammad 410, Polly Umrigar 380, Imtiaz Ahmad 375, Chandu Borde 330, and Nari Contractor 319 were the top scorers of the series. Ramakant Desai 21, Haseeb Ahsan, Mahmood Hussain 13, Bapu Nadkarni 9, Fazal Mehmood 9, and Subhash Gupte 8 were the top wicket-takers of the series.