There was a story that when Bradman imposed a curfew on the team, Keith Miller presented himself at the captain’s door dressed in his evening clothes. The most astonishing point about Keith Miller and his character, which was the key to his bowling, is that he did not come from Sydney originally but from Melbourne.

To Australian cricket, Melbourne is what the north is to England—the home of the game’s more defensive, stoical form. Perhaps climate and the degree of latitude determine both cases. In any event, only Melbourne could have raised Woodfull, Ponsford, and Bill Lawry, while Sydney—hotter, freer, and more flamboyant—was the home of Victor Trumper, Stan McCabe, and Doug Walters.

Yet Keith Miller was born in Melbourne, went to school there, and learned to play Australian Rules (a sport based in Victoria) to the highest standard. He did not, naturally, like the approach to cricket there, especially that of Woodfull, who taught at his school. Nevertheless, he had graduated to the Victorian team as a batsman when the war came. Once it was over, he moved to New South Wales, where he could, so to speak, air all his strokes: outside cricket, he could cut a dashing figure at the races, in classical music halls, and in the cockpit of fighter planes (he was named after the early aviators Keith and Ross Smith).

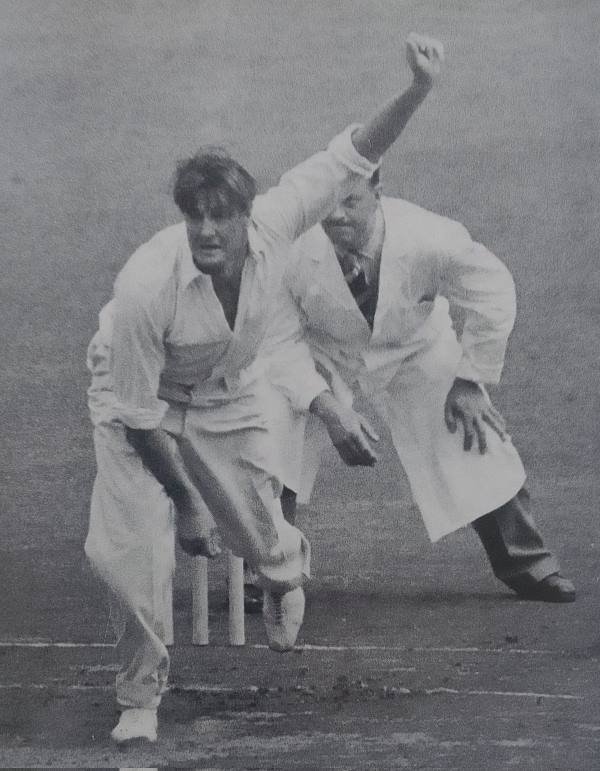

It was not until after the war that Keith Miller took up bowling in earnest (it is so easy to forget that he was initially a batsman who hit 41 first-class centuries), and now his dare-devilry could be fully displayed. He had Botham’s shoulders and a sense of adventure, fine rhythm, and a love of variety. Tossing his hair back into place after each ball, he might bowl a googly in his opening over, as fast as it is possible to bowl one; the next ball might be delivered off a run of five paces, although his full run-up was barely more than Sunday League length.

Unlike Ray Lindwall, he had a high level of action, and when it was combined with his natural virility, he was a fuller follow-through than Jack Gregory, and with his hostility when in the mood, he was the most aggressive of his era. Keith Miller was helped too by the frequency of new balls in his time. Until 1946, it was the practice for a new ball to be available after every lot of two hundred runs had been scored in an inning.

From 1946 to 1949 in England, the change was made to after 55 overs, presumably to assist bowlers in a high-scoring period. This suited Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller ideally. Then, until 1955, a slight alteration was made in England to 65 overs. (As the number of overs was not recorded on scoreboards in those days, a white flag had to be displayed after 55 overs, a yellow one after 60 overs, and both together after 65.) Throughout his fast-bowling career, Keith Miller was formidably equipped.