The sight of Kerry O’Keeffe as one of Australia’s main bowlers in England signifies more than this spinner’s personal comeback from two years out of Test cricket. In the crowds at Lord’s and Old Trafford were people who had almost forgotten what a leg-break action looked like.

Since 1972, England had not seen a player hand a green Australian Capitan umpire and dismiss a Test batsman with a leg break unless they happened to be at Headingly one day when Ian Chappell, as a last-change bowler, landed his only wicket among the 75 the Australians took in the four Tests of 1975.

You’d have to be in the late fifties or older to remember a pre-war tour in 1934, on which leg-spinners Bill O’Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett shared 53 wickets in five Tests. Captain W.M. Woodfull mostly used them in teasing tandem with Clarrie Grimmett into the wind. Kerry James O’Keeffe was born on November 25, 1949, three years after a knee injury ended O’Reilly’s career at 144 wickets in 27 Tests.

Without having seen ‘Tiger’ bowl, he developed a googly action at an above-average pace for leg spinners. As a fifth-year pupil of Marist Brothers, Kogarah, O’Keeffe had instant success, taking five wickets in his first bowl for St George in Sydney first-grade cricket. This club’s honor boards enshrine the deeds of O’Reilly, Bradman, Lindwall, Morris, and Norman O’Neill. After touring India with the Australian Schoolboys at 17, he was chosen for the New South Wales Colts.

Kerry O’Keeffe’s state debut at 19 was on a Sydney green top where Peter Allan (Queensland) took 13 wickets and David Renneberg took 12, but don’t jump to the conclusion that this influenced Kerry to push the ball through in rivalry. Sid Barnes once suggested tying an anchor to his arm, but neither O’Reilly (even quicker) nor Coach Peter Philpott recommended altering his pace.

The main difference noted by Bill O’Reilly (whose bowling strategy was based on the leg break) was that Kerry launched a larger quota of top spinners and wrong ones, besides an infrequent old-style off-break. Note the wide turn of the ball with his unorthodox grip. O’Keeffe has chiefly earned his wickets by nagging accuracy at a trajectory that dissuades even nimble batsmen from coming down the track.

Kerry O’Keeffe’s height of 6 feet 1 inch aids the bounce, which supplements his spin. In his first Test at 21, two nasty surprises were bouncers from Peter Lever and John Snow bruising his chest, and a couple of Englishmen questioning his off-break as a suspected chuck. No more was heard of that in his matches before umpires in four countries. Omission from the 1972 tour of England rocked him to the heels. Though his wickets for Somerset in 1971–72 included 7 for 38 against Sussex, many doubted whether two county seasons benefited his bowling.

Kerry O’Keeffe’s approach, delivery position, and too-overhead angle of his hand all urged the ball inward to right-handers. As if peeved, his leg-spinner went into hiding. In helping Australia win a Trinidad Test in 1973, his bowling came off like quick off-breaks. But Australia often had off-spinner Ashley Mallett as the sole spinner (125 wickets in 35 Tests), and there was keen rivalry between Kerry and South Australian leg-spinner Terry Jenner. After both toured the West Indies in Mallett’s absence, the selectors preferred Jenner against Mike Denness’s Englishmen in 1974–75.

The name O’Keeffe was missing from the Australian XI for two disconsolate years. Two changes have earned O’Keeffe exclusive rights at last as Australia’s leg-spinner. His delivery angle has been adjusted, and he is also less concerned about his game. His habits had crept in unnoticed until he saw a film of his bowling. He worked on corrections at practice until, at last, he felt it was time to use his remodeled delivery in matches. Wooed out of hiding, his leg-spinner brought the largest quota of his 68 wickets in 14 matches last season in Australia and New Zealand.

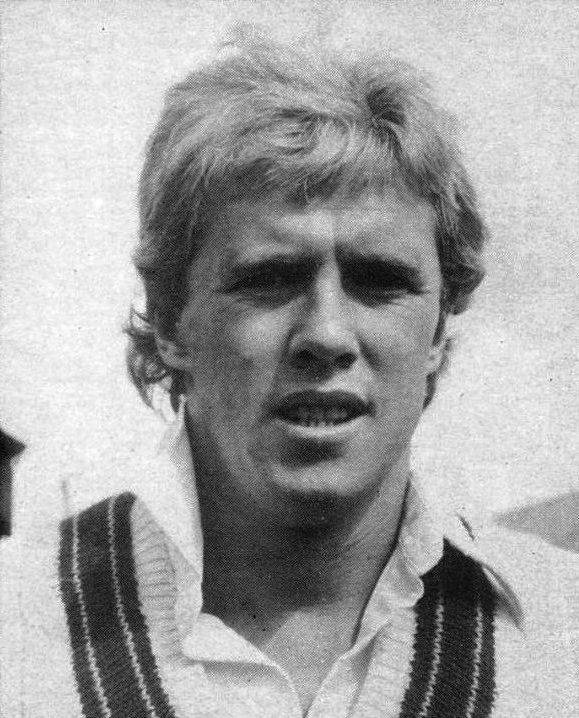

Only Dennis Lillee took more. Against Pakistan in Adelaide, after Jeff Thomson’s shoulder injury, O’Keeffe and Lillee bowled 65 of one day’s 84 eight-ball overs. A more relaxed and successful O’Keeffe had 50 wickets in 21 Tests before his selection to tour England this year expunged the last smudge of his dismay in 1972. Welcoming Kerry’s statement about less worrying, ex-captain Ian Chappell joked about a halt to silver threads among the blonds.

In dressing-room fun, Kerry O’Keeffe would say to one of a conversing pair, ‘You’ve dropped some money. Seeing a banknote beside his foot, the man would stoop, but the note vanished from his fingertips, whisked away by a retractable thread too fine to be noticed. Captain Greg Chappell called on Kerry O’Keeffe as early as the 22nd over in the Jubilee Test at Lord’s.

Dropped off Kerry at mid-on at 26, Derek Randall miscued his wrong-un near his leg peg. Bob Woolmer also got away with a couple of French cuts. His first wicket was from Captain Mike Brearley, who could not keep a bouncing wrong’un out of close-leg Richie Robinson’s reach. In the second Test, a similar ball dismissed Woolmer at 137, but the close catcher was Ian Davis.

Kerry O’Keeffe hit the stumps of his third victim, Underwood. A chafed finger handicapped him in this test, but neither he nor left-hander Ray Bright could extract much turn from the Old Trafford track except when the ball landed in boot marks. On the last day, Kerry switched to around-the-wicket, seeking roughened spots, and was rewarded when Mike Brearley’s cover drive flew to Doug Walters.

Kerry O’Keeffe’s reach is an asset in his gully fielding. For Alan Knott’s daring over-the-top slash, he was switched deeper to fly-slip at Old Trafford and dived forward to make the most spectacular catch of the Test. A straight bat is the most conspicuous part of his batting. His highest Test score is 85 against New Zealand at Adelaide, where he and Rod Marsh put on 168 to lift the Australian seventh-wicket record from Clem Hill and Hugh Trumble, 165 at Melbourne in 1897–98.