There have been faster bowlers than Dennis Lillee, but not many. There have been more hostile fast bowlers, but not many. Spofforth, Ernie Jones, Constantine, Heine, Charlie Griffith, Andy Roberts, and Jeff Thomson have brought menace, even terror, to the bowling crease. But Dennis Lillee concedes nothing to any of them. He is one of the great fast bowlers of the twentieth century, possessing a full set of gear changes, a knowledge of aerodynamics equal to Ray Lindwall, an abundance of stamina and determination, and more courage than is given to most.

He needed that courage in 1973 and ‘1974 when he set about achieving one of the sport’s most impressive comebacks. The four stress fractures in the lower vertebrae would have finished many a career. Dennis Lillee, having dramatically bowled his way to fame, was faced with six weeks in plaster and a long and grueling fight to full fitness. He withstood the punishment and handsomely repaid those who had worked with him and believed in him. He played cricket again, though only as a batsman.

Then he put himself in the bowl. No twinges. At the end of the 1973–74 season, his hopes were at least as high as those of his notorious bouncers. England arrived the next season to defend the Ashes in six Test matches. Lillee pronounced himself fit and dismissed Ian Chappell two or three times in early-season interstate fixtures. Australia selected him again.

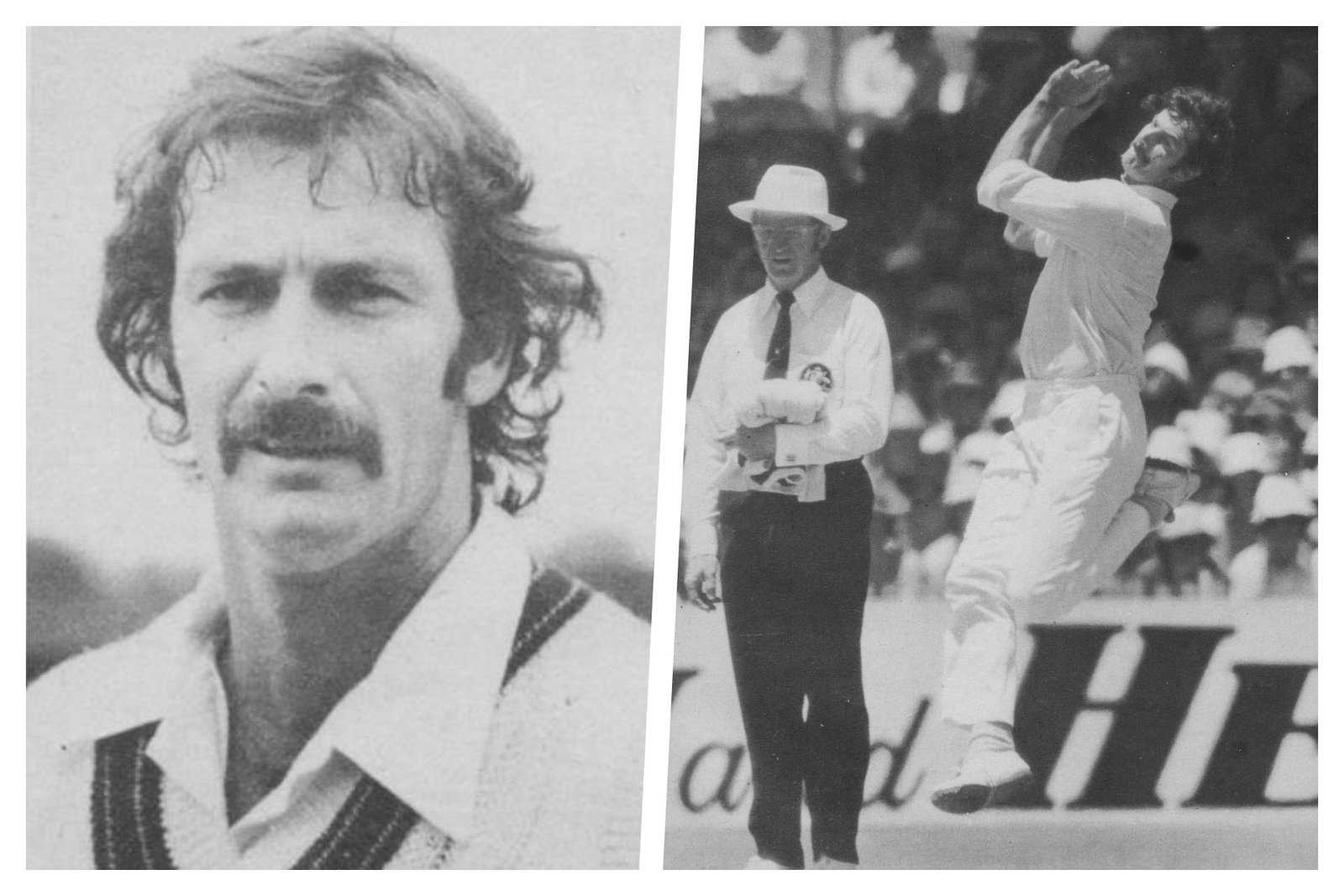

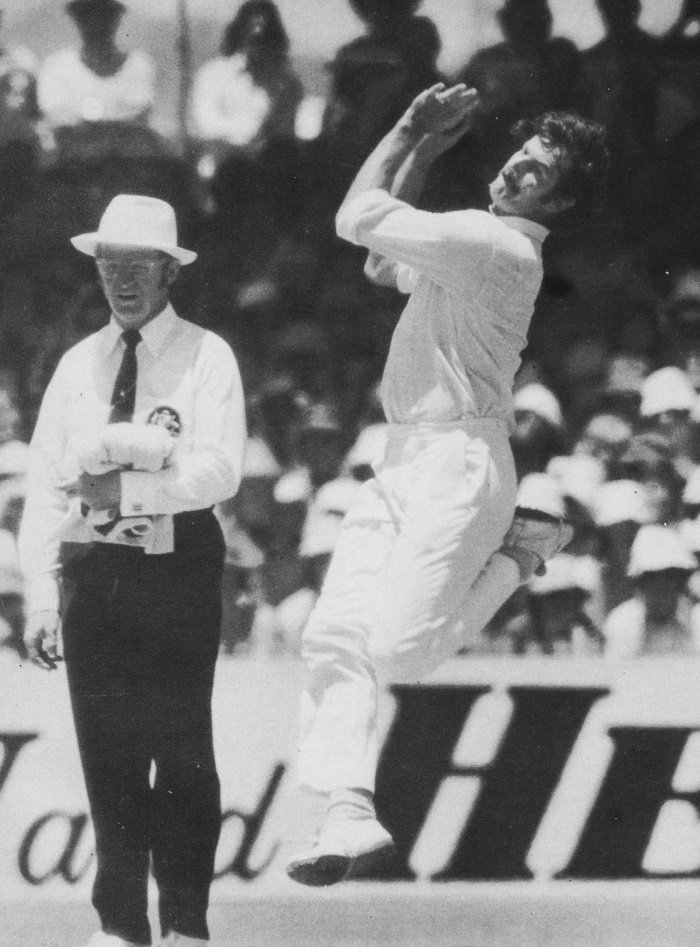

And in the first test, a new extermination firm was formed: Lillee and Thomson. England’s batsmen in Brisbane would just as happily have taken their chances in the company of Leopold and Loeb, Browne and Kennedy, or, at the end of the day, Burke and Hare. It was devastating, still fresh in memory. Australia’s opening pair took 58 wickets in the series out of 108 that fell to this despite Thomson’s withdrawal through injury halfway through the fifth Test and Dennis Lillee’s after six overs with a damaged foot in the final match. The full force of this controlled cyclone was felt in the 1975 series, though England’s sleeping pitches absorbed some of the energy. This is when Lillee’s other bowling skills asserted themselves.

As in the 1972 series, when he took a record 31 Test wickets, Lillee beat batsmen by change of pace and with his wicked away swinger. Rod Marsh and the ever-expectant slip-cordon did the rest. He had more support now: from the tireless Walker, from Gilmour (who would have strolled into any other Test team in the world), and from Thomson whenever he had his rhythm. This winter, interrupted only by pleurisy, he has gone on to torment and punish the West Indians, taking his hundredth Test wicket in the process.

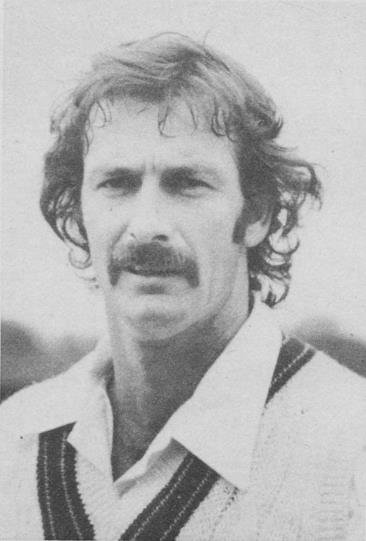

Still, that remade and wonderfully broad back held up against the pounding constantly dealt to it by its owner. Dennis Lillee’s inspiration, when only a boy, came from a West Indian: Wes Hall, the genial fast-bowling giant. The young fellow from Perth, born on W. G. Grace’s 101st birthday (July 18, 1949), clambered with all the fervour of a Beatles fan into the members’ enclosure at the WACA ground just to be near his idol.

There was also Graham McKenzie, the pride of Perth, to fan the flames of his ambition. And Fred Trueman. And Alan Davidson. Not that this was enough. There had to be an inherent talent. The tearaway with long sideburns, who stormed in over a long distance and hurled his wiry body into delivery with every ounce of his might, eventually played for Western Australia. By 1970–71, he was considered good enough to play for Australia-one of the hopes in a reshaping of the national eleven.

He took 5 for 84 against England at Adelaide in his maiden Test, opening the attack with another young aspirant, Thomson-Alan (‘Froggy’), not Jeff. A season of Lancashire League cricket with Haslingden followed. Next, he bowled against a conglomerate team billed as the Rest of the World. In Perth, he decimated them with 8 for 29, including 6 for 0 in one red-hot spell (when he wasn’t feeling too well!): Sunil Gavaskar, Farokh Engineer, Clive Lloyd, Tony Greig, and Gary Sobers were among the victims. The real world at last took notice and wanted to know all about him.

He was learning all the time, especially when trying to bowl to Gary Sobers during his indescribably brilliant 254 at Melbourne, when straight drives came bouncing back from the boundary before the bowler had raised himself upright in the follow-through. Yet he continued to harass the tourists, not by any means now trying to bowl every ball at top speed. If England in the spring of 1972 thought Australian claims of Dennis Lillee bounce and penetration were exaggerated, the threat was soon a vivid reality. He has sometimes attacked batsmen with his tongue and been denounced for it. Brian Statham used to let the ball do all his talking.

Fred Trueman ripe language was somehow not the antithesis of geniality. Dennis Lillee’s ‘verbal aggression’ has been something else in its spirit of near-hatred. One could name others in cricket history who have gone about their business in this way, only to be left with the feeling that, in each case, the bowler has failed in one respect to do himself justice. Lillee was a central figure in Australia’s re-emergence as a formidable side, and a great deal has continued to be expected of him.

The chanting of the crowds, the persistent publicity, the inescapable typecasting, and the need to transpose celebrity into real-world security must take a man away from himself, at least in part. A truth that will remain is that Perth has given to cricket a fast bowler of hawk-like countenance and perfect physique for his purpose, whose flowing approach and superb athletic action have been a thrilling spectacle for young and old, male and female, pacifist and warrior.

Related Reading: Dennis Lillee Famous Remarks of Making His Grave on Faisalabad Pitch

Source: David Frith article of 1976