Do We Really Need Green Wickets? The first Test against India ended in an inevitable draw where neither side was able to ground down the other with ruthless courtesy. The complete compendium of five days would be that Pakistan won the toss and batted first, maintaining a good run rate and piling up 503 runs. Majid 47, Sadiq 41 (who constantly changed helmet for cap and back to helmet; it pleased no one—annoyed all), then Zaheer Abbas, getting the Indian spinners by the nape of their necks, collected a superb 176 runs.

Javed Miandad’s well-managed batting produced a gritty 154 not out. In the second inning, Zaheer and Asif Iqbal got together, and with these two batting together, the situation was, “Anything you can do. Zaheer Abbas missed what would have been his second hundred of the match by four runs, but Asif went on to score his 9th Test hundred. Indians went in under heavy pressure; the diminutive Gundapa Viswanath scored a magnificent 145, followed by Sunil Gavaskar and Dilip Vengsarkar, who also batted with purpose and managed 462 runs for 9 at this stage.

However, Bishan Singh Bedi declared the innings closed. We were told by the experts that the wicket would play fast; if so then our speedsters made no effective use of it; instead, they bowled a battery of no balls, short pitched and wildly off the target deliveries, which disturbed and irritated all but the Indian batsmen. Coupled with fielding lapses, the position was superlatively worst. Iman Khan, now the quickest of all the bowlers we have so far presented in international cricket, at times did all but hit his own toe.

Sarfraz Nawaz was no different either, and as Sikander Bakhat tried time and again to bowl fast and extract life from the wicket, I began to fear he might rupture his rib cage. Had our bowers bowled a little short of good length deliveries well up to the batsman on or about the off stump, the story might have been different. The experts then said it would take spin-my-eye! It didn’t!

The late Sir Larie Constantine said, Aim for the wicket; if the batsman misses, he is out, and if he tries to deflect it into various gaps, he is living dangerously.” So, on an unresponsive wicket, these should have been our tactics. However, both the skippers and their team members joined hands with the commentators and blamed the wicket for being so slow and unresponsive to spin and speed—a suitable justification found for a drawn game.

From there we went to Lahore and were told by the connoisseurs of the game that the wicket there would play fast, which it did on the first day, presumably due to generous watering and roll line during its preparation and the presence of dew, but as the match stretched further it became as docile as ever. In the first hour of the first day the call did wobble a bit in the air and off the wicket, and as a result of it, the Indians were bundled out for 199 runs.

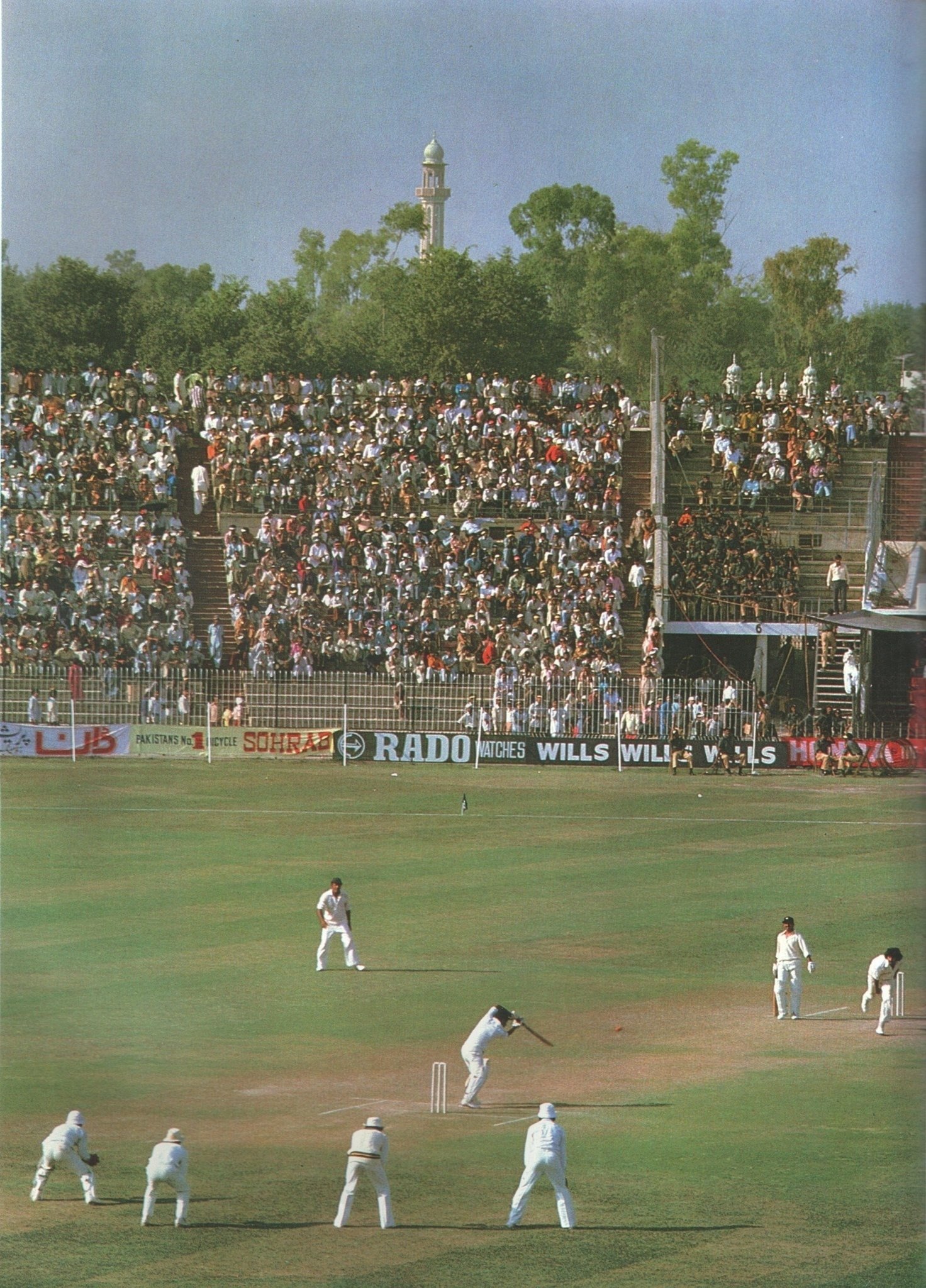

Pakistan went in, and Majid Khan produced a thoughtful 45, playing second fiddle to Bari, who sent in as a night watchman after the fall of Mudassar turned into a nightmare for India. Majid Khan dismissal brought in Zaheer Abbas, who unleashed a repertoire of strokes and gave an unforgettable performance, undoubtedly one of the best innings ever played in the history of the game anywhere by any batsman, beauty and quality. No expletives of the English language would adequately describe the manner in which he went about to amass 235 runs—he was simply magnificent. His run galore turned Qaddafi Stadium into a promenade; the nimbleness of his footwork made even Rudolf Nureyev look a novice—why call him Bradman of Asia? Just call him Zaheer Abbas from Pakistan.

Indians in the second innings made a marvelous recovery—hats off to Gavaskar, Chauhan, and Viswanath—and just as they looked well set to save the match, Mushtaq brought Mudassar on, who turned the tables and got rid of Viswanath and Vengsarkar in quick succession. From then onwards, Pakistan XI was all over India and eventually won the match by 8 wickets.