For whose benefit? Haresh Munwani analyses the pros and cons of the Indian Cricket Board’s decision to start a benevolent fund for past test cricketers in 1985.

After well-nigh eternity, India (BCCI), the richest sports body in the country, has decided to recognize the contribution of those cricketers who represented the country between 1932 and 1976. While the present lot of cricketers have suitably benefited from the BCCI’s healthy coffers, those that helped India achieve Test status were sadly neglected.

According to A. W. Kanmadikar, who, at the time of writing this item, was the honorary secretary of the BCCI, “On the recommendations of its financial committee, the Board has decided to pay 2000 rupees per Test match played to those cricketers who retired before 1-4-76. Those players who have changed their nationalities will not be eligible”. Oddly enough, the Board’s announcement tactfully avoided any mention of when these payments would be made.

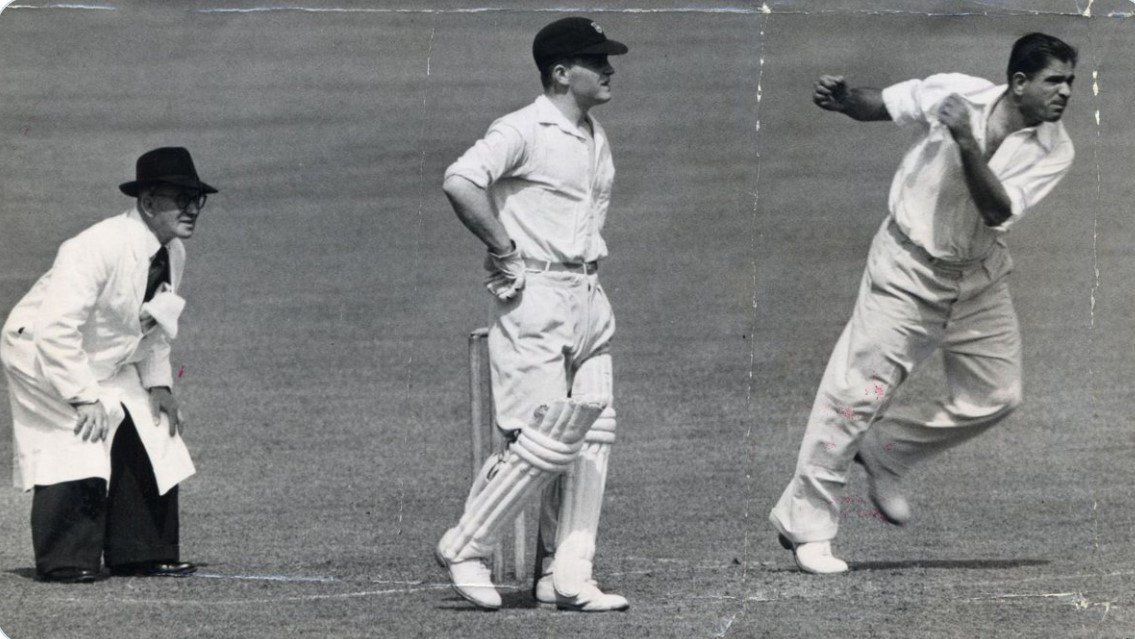

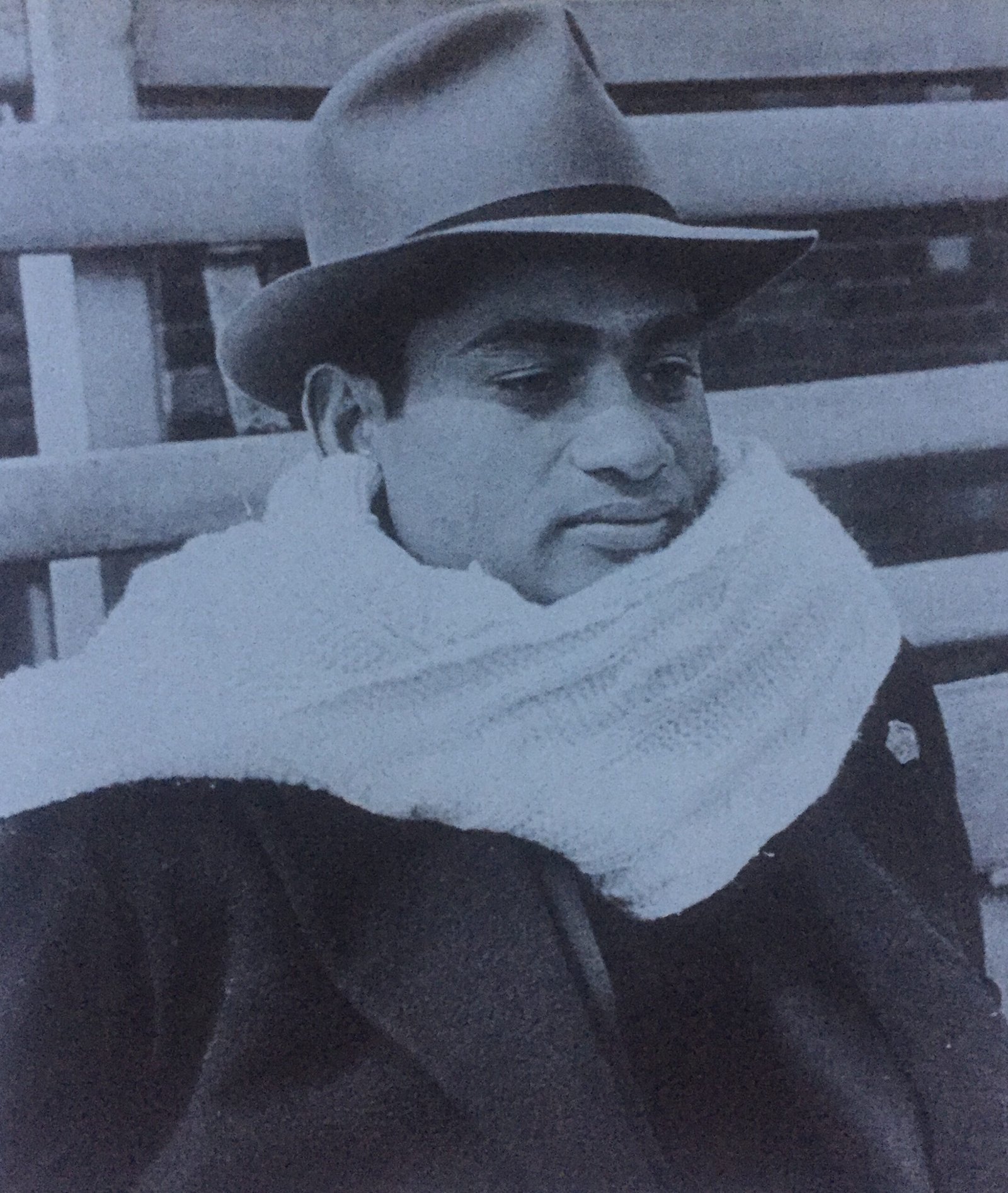

Commenting on the Board’s decision, former Test cricketer Polly Umrigar, who initially submitted the blueprint of this scheme to the Board, said, “While we are thankful to the Board for compensating in whatever way it sees best, those that had toiled for the nation, the Board’s guidelines in making these payments make unpleasant reading.” Elaborating on his remarks, which were constructive rather than critical, the former chairman of the selection committee opined, “For reasons best known to them, the BCCI has decreed that those who have represented India in official, as well as unofficial Test matches, will not be paid anything for the latter. In what way were the Commonwealth sides that visited India in the early 1950s different from other Test sides?

I would even say that these Commonwealth teams were far stronger than the other Test teams. Besides, as far as we were concerned, when we played the Commonwealth sides, we were still playing for India, thus separating between official and unofficial matches Test cricketers are, in one stroke, dismissing the efforts of stalwarts like Vijay Hazare. Shifting to the human aspect, Polly felt that the Board’s decision not to make any payments in the case of those cricketers who had expired was a bit harsh. Explaining the thinking that went behind this move, Kanmadikar revealed, “The Board does not want to get involved in any litigation that may result in the legal heir of the deceased cricketer being someone other than the widow.” Retorted Polly, “In that case, the ‘Board could have stipulated that payments would be made to widows only.

After all, it is the woman who has made all the sacrifices, while her husband was playing for the country. Moreover, you cannot expect any elderly woman to work for a living, which is why her need for money is greater. The children can always fend for themselves but an ageing lady cannot. And as far as possible litigation is concerned, because of the odd case, you cannot dismiss the claims of the others,” said Umrigar. Be that as it may, this concept of making payments to ex-test cricketers originated with Umrigar’s letter to BCCI president, N.K.P. Salve on May 2, 1984.

In his letter, Polly Umrigar pointed out the flaw in Rule 7 for the award of Benevolent Fund’ framed by the Board, which read: “Notwithstanding anything contained in these rules, a player who has retired or ceased to play before 1-4-76, shall not be entitled to any benevolent fund under these rules”. Further, the letter mentioned, “I feel that this is very unfair to old cricketers who have also served the country in the best traditions of the game. Injustice has been done to players like Vijay Hazare, Dattu Phadkar, Chandu Borde, Bapu Nadkarni, Ramkant Desai, myself, and others who have played a large number of Tests and yet have not benefited from the rule since we retired or ceased to play before 1-4-76.”

That Polly Umrigar had thoroughly evaluated the pros and cons of the issue at hand is borne out by the fact that he suggested that in case the Board did not wish to burden its resources, it could raise the amount to be paid as a benevolent fund by levying a surcharge of five “rupees on test match tickets. Justifying a payment of 5000 rupees per Test match as against the 4000 rupees dished out to present-day cricketers from the benevolent fund scheme, Polly Umrigar, who was paid the princely sum of 65 rupees when he made his Test match debut, argued,” Because the frequency of Test matches during our time was far less as compared to today, the extra 1000 rupees would bring ex-cricketers on par with the present-day generation as far as raising benefit amounts went. 31 The logic in Umrigar’s letter appealed to the BCCI, who next asked him to submit a formal blueprint.

Drawing up a list of cricketers, some of whom had legendary names like Vijay Merchant, Mushtaq Ali, Vijay Manjrekar, Vinoo Mankad, Lala Amarnath, and Umrigar, we found there were 80 of them living and 25 dead. While treating both categories as one, Umrigar recommended that the maximum amount payable per match should be 5000 rupees, while the minimum should be 3000 rupees. Consequently, the board will have to make payments ranging from 55 lakh rupees to 33 lakh rupees, respectively.

After sitting on the matter for a little over a year, a process that was considerably hastened because of the circumstances connected with the death of Dattu Phadkar, the BCCI decided to make payments at the rate of 2000 rupees per match. “The BCCI cannot make these payments immediately without causing considerable strain on its finances, informed Kanmadikar. The BCCI shall raise this huge sum by staging a one-day game between the 1987 World Cup champions and the Rest of the World at Calcutta, soon after the Championship final.

Read More: Pankaj Roy – Most Prolific Opener Before Gavaskar