A Great Occasion in India: Four West Indian Pace Bowlers in India 1963 in Action by Rusi Modi A festival cricket match was organized in Bombay to augment the National Defense Fund, in which leading Indian cricketers participated, as well as the four fast bowlers from the gay Caribbean—Staters, King, Watson, and Gilchrist—who have been engaged as coaches by the Board of Control for Cricket in India.

The outstanding performance of this three-day match between the Governor’s XI and the Chief Minister’s XI, played at the Brabourne Stadium, was that the public of the city of Bombay enabled no less than two crores of rupees (approximately £150,000) to be added to the National Defence Fund, including contributions, of course.

The rival captains, Amarnath and Mushtaq Ali, heroes of the past, infused the right spirit into a game of this description. The four West Indian quick bowlers—two playing for either side together with Amroliwalla, who scored 85 and 51—demonstrated how such fixtures should be played. Young Duleep Sardesai, Polly Umrigar, and Sudhakar Adhikari, too, with their contributions of 86, 62, and 83, respectively, helped to keep the large crowd in good humor.

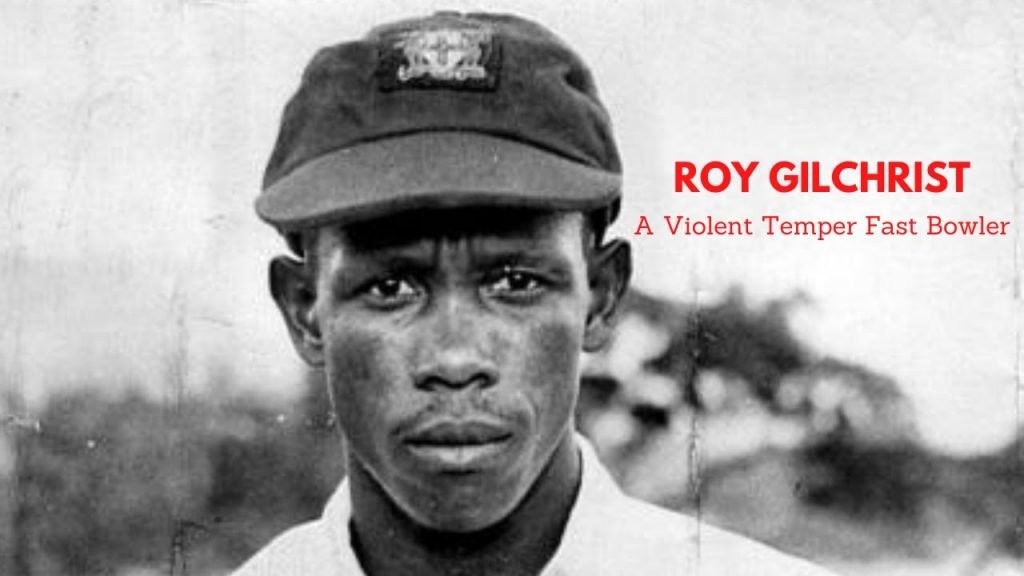

And it was only on the last day, during the closing stages of the match, that some renowned cricketers of the Governor’s XI did not give up their inherent seriousness and go all out for a win. Set to score 191 runs in as many minutes, they collected only 175 for the loss of eight wickets. Roy Gilchrist’s first ball was of terrific velocity, which reared like a missile and just missed the batsman’s head!

But soon Roy Gilchrist got control of himself as well as of his direction, and although not as quick as in 1958 when I last saw him, he is definitely a better bowler today, varying his pace and direction. Since then, he has also developed the away-swinger, the batsman’s hoodoo. King, the only one of these four West Indies bowlers selected to tour England in the summer of 1963, provided the best bowling in the match on the dull Brabourne Stadium wicket.

King can move the ball either way, his speed being medium-fast, and in collaboration with the burly Barbadian, Wesley Hall, may well provide a formidable combination for England to encounter, provided they attack the stumps and do not frequently send down balls the batsman need not play. These four fast bowlers, engaged as coaches, can give excellent practice to the up-and-coming Indian batsmen, who are generally weak at tackling the out-swinger.

Indian batsmen, as a rule, are quite at home against balls coming into them but simply cannot cope with the ones that leave the bat in a hurry. The flaw lies in their footwork and technique, which are three-fourths of the job. Temperament, of course, has its say. The majority of Indian batsmen are not lacking in temperament as a rule, but they certainly lack technique and footwork.

If these coaches can remedy this major flaw, then there is enough batting talent in the country to produce batsmen of international class in the years to come. And we certainly need a handful, as both Umrigar and Manjrekar, our prominent run-getters, have said goodbye to Test cricket. At present, there is a tendency among most of our seam bowlers to concentrate on in-swingers alone.

Let us hope that the West Indian coaches will teach our young seam bowlers the art of bowling the away-swinger, which has fallen into desuetude, for the out-swinger, which is the first requisite of a class seam bowler. The reason why India has not been able to produce stroke players and good pace bowlers during the last decade, with a few exceptions, is mainly due to the nature of the wickets that exist in the country today.

The majority of our pitches are slow and lifeless and are of no help to the bowler, nor do they encourage the batsmen to execute shots. The result is that the straight drive, the most elegant shot in the game, especially off a fast bowler, is seldom, if ever seen these days. And as stressed by no other person than the great Australian captain Richie Benaud, when he addressed a meeting in Bombay in 1959, the sooner we do away with over-prepared clean-shaven wickets and produce ‘green lively wickets’, the better for all concerned.

A decade ago, the wickets in India were not so bad. The Gymkhana Ground in Bombay, the nearest approach to an English wicket and the venue of all first-class matches till 1937, was abandoned in favor of the Brabourne Stadium. This was most unfortunate, as the Bombay Gymkhana wicket afforded equal scope to the bowler and also the batsman, thereby putting more life into the game.

The lovely Chepauk wicket in Madras, a replica of the Parks Ground at Oxford, was similarly abandoned in favor of the Corporation Stadium in 1959. Speaking personally, a 50 on the Chepauk or the Bombay Gymkhana wicket gave me far more pleasure and satisfaction than a double century on the placid Brabourne Stadium wicket! On account of the tremendous success achieved by the festival match, efforts are being made by the Board of Control for Cricket in India to get a team from abroad to play a few matches in aid of the National Defense Fund.