Harold Larwood – Nothing that has happened in international politics in my lifetime is as dramatic and miraculous as Harold Larwood’s return to Australia as a welcomed emigrant. The cordial post-war reception given by German crowds to Churchill was less astonishing, and I shall not admit that Larwood’s feat is eclipsed till his holiness the Pope is applauded all the way around Moscow’s Red Square by Party ticket-holders.

The Australians had, according to their lights, something to forgive Larwood for. When Douglas Jardine’s team reached the sub-continent in 1932, Australia held the Ashes. The side Bill Woodfull had led to England two summers earlier had won the rubber and wiped out the stigma of the heaviest Australian defeat at the hands of Chapman’s team.

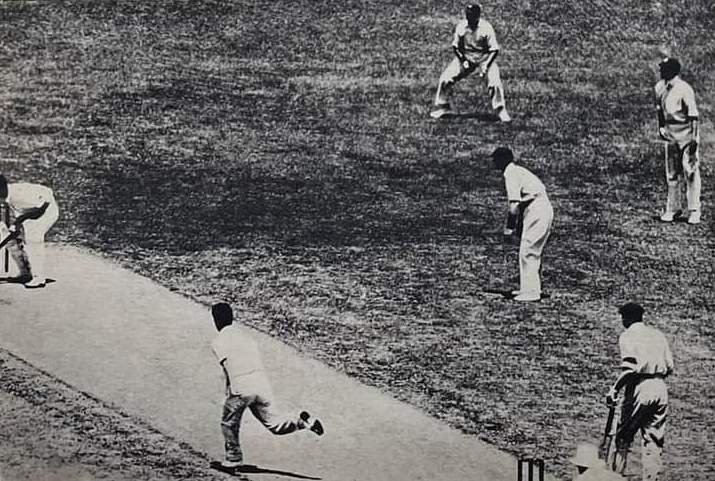

By ’32, Bill Woodfull had strengthened that victorious team. The batting had remained static, except for the advent of Jack Fingleton; but the bowling was certainly stronger. Bill O’Reilly had arrived, and Bert Ironmonger was available. There was no reason to suppose that Australian ascendancy was to be challenged. And then came Harold Larwood. He came, as I remember, in that First Sydney Test, bowling with the Pressbox behind him, with Allen, Voce, Maurice Leyland, and Hedley Verity craning forward at short leg and silly mid-on.

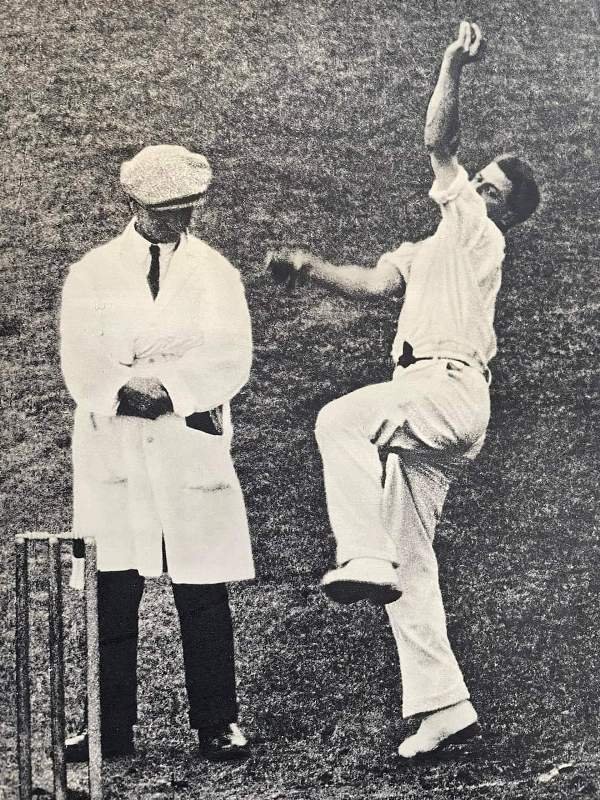

He bowled faster than I have ever seen anyone else bowl; faster than Ray Lindwall, far faster than Cuan McCarthy. He bowled, according to my memory, many fewer bumpers than Voce; but he rose, at a terrific and dangerous pace, to threaten the short ribs; to threaten the heart. If you played a stroke at him, it was apt to be a defensive dab liable to land the ball in the hands of that on-side field.

Such was leg-theory: and Harold Larwood was the theorist translated into lightning action. Those who argued against the new form of the attack said it wasn’t cricket. It got its effects; it got its wickets, from intimidation. Those who defended it said: ‘No game is worth playing by men without a spice of danger. Here is the game. There is the danger. Where are the men?”

The judgment of history has gone against fast leg theory or ‘bodyline.’ It is outlawed now, though regrettably and inconsistently — bumpers do still get wickets, by something like intimidation. That was how Compton lost his, at Nottingham in 48. It remains to say that Harold Larwood under Douglas Jardine was the most accurate fast bowler of our time. He took 33 wickets in Tests during that tour — 16 of them clean bowled. As a batsman, he had one unforgettable day. That was when, by lion-heated driving, he brilliantly batted in the Fifth Test at Sydney.

After bowling 32.2 overs in the Sydney test 1933 Jardine angers Larwood by telling him to “put the pads on” as night-watchman. Seething even the next morning, he attacks “the bowling at every opportunity” for 2 hrs and 20 mins for 98. The Mob salutes him. The Australians clapped him all the way back to the pavilion.

Larwood recalled, Every man on Sydney Cricket Ground stood and cheered me. The applause and the cheers from the mob on the Hill were thunderous, I never realized the approach of Australian crowds until that moment, It proved to me Australians like a trier, they go for the underdog, and they appreciate good cricket no matter who provides it. They are tough: they barrack to unsettle a player but they like any one who attacks. I never expected the Hill mob to get up and cheer me after the abuse they had hurled, If 1 had that time over again I would get those two extra runs. Either that or they never stopped clapping Bert Ironmonger for holding almost the only catch he ever held in his life.