Pankaj Roy was one of those who lived up to the early promise he held out. By scoring a century on debut in the Ranji Trophy in 1946–47, scoring in inter-university matches, and hitting an unbeaten century against the strong West Indian team of 1948–49.

India’s Most Prolific Opener Before Sunil Gavaskar

Pankaj Roy, who passed away in Kolkata in the early hours of February 4, 2001, was the foremost Indian opening batsman throughout the fifties. The best tribute to him would be to point out that his tally of runs was the best for a specialist opener till a certain Sunil Manohar Gavaskar came along.

Adjectives like stylish or elegant were hardly used to describe Roy’s batting. The qualities associated with him were generally dedication, determination, and concentration. A short, rather stocky figure, Roy had a solid defense, but he could also attack when the need arose, being particularly forceful off the back foot.

His famous first-wicket partnership of 413 runs with Vinoo Mankad—still a Test record—was the jewel in his crown. However, there were many trinkets along the way, too. Roy’s obdurate qualities were just what Indian cricket required during the time he opened the innings, for the batting was generally weak.

As he came on the scene, players like Vijay Merchant, Mushtaq Ali, Lala Amarnath, and Vijay Hazare were on the way out. It was impossible to replace these greats overnight, and Indian batting in the 1950s was generally brittle. The opening slot, in particular, had gaping holes.

However, Pankaj Roy’s stubborn batting, built on a rock-solid defense, helped at least to fill these holes in the part. Roy was one of those who lived up to the early promise he held out. Roy also scored a century on their first-class debut in the Ranji Trophy in the 1946–47 season.

Also, by tall scores in the inter-university matches and by hitting an unbeaten century against the strong West Indian team of 1948–49. Whereas, still at college, he made it known very early that there was an uncommonly gifted batsman. And yet, in his first series, he exceeded even the highest expectations.

Against England in 1951–52, he scored 140 in his second Test and followed this up with 111 in the final triumphant Test at Madras. Two centuries in his maiden series saw Roy hailed as the new boy wonder of Indian cricket. He went on the 1952 tour of England with his confidence level on a high but came from the trip with his technique and temperament being questioned.

On that disastrous tour, Roy was one of the main failures. In seven Test innings, he got five ducks, four of them in a row. Shrugging off the shocking run, Roy rediscovered his touch in the West Indies in 1953, proof of this being cemented with his double effort of 85 and 150 in the final Test at Kingston.

Pankaj Roy and Vijay Manjrekar added 237 runs for the second wicket, an Indian record that stood for almost 26 years. No one questioned Roy’s technique and temperament after that. Sure, the cynics pointed out certain flaws in his batting, especially against fast bowling. But runs are the final result that no one can argue against, and Roy kept scoring them consistently.

After all, no one can finish with a tally of 2,442 runs from 43 tests at an average of 32.56 with five hundred if he is lacking in technique and temperament. There were doubts about whether wearing spectacles, which he resorted to in the mid-fifties, would affect Roy’s batting. It was not in any serious manner, and he played with reasonable success.

He answered charges that he was vulnerable to fast bowling by scoring 334 runs in the series against the West Indies in 1958–59. In this series, he faced a barrage of bumpers and beamers from Wesley Hall and Roy Gilchrist. Whatever the cynics might have said about his technical limitations, even they did not question Roy’s courage. For example, in the first Test at Bombay, he batted 445 minutes for 90 in an effective rearguard action.

On his second tour of England in 1959, Roy did better both in the Tests and first-class games. Still, it was not a record in keeping with his reputation as one of the side’s most experienced batsmen. In first-class matches, he scored 1,207 runs at an average of 28.73. In the Tests, he started off well by top-scoring with 54 and 49 in a losing cause in the first game. Thereafter, however, memories of 1952 haunted him, and in eight subsequent innings, he got only 76 runs.

Once he was back home, Roy was more successful against Australia, scoring 263 runs, including a heroic 99 in India’s defeat at New Delhi. But the fact that he fell five times in the series to the left-arm swing of Alan Davidson did seem to indicate some technical deficiency against the fast, moving ball.

Yet in 1960, Pankaj Roy was still where he was at the start of the previous decade—more or less entrenched as India’s. No one could have guessed that the end of his career was around the corner. But this did come about suddenly after scoring 23 in the first Test against Pakistan in 1960–61. Therefore, he was dropped, never to be considered, and determined to make a comeback.

Pankaj Ray made a packet of runs in the Ranji and Duleep Trophy competitions to show that he still had something to offer Indian cricket. But he never got a look-in again, and his heroes were limited to playing for Bengal, for whom he remained a tower of strength. His tally of 6,149 runs at an average of 66 with 21 hundred still makes for an impressive surpass.

In later years, Roy served on the national selection committee, watched his nephew Ambar and son Pranab Roy play for India, and became one of Kolkata’s prominent citizens, including the Sheriff of the city. But in a crowded, eventful panorama, there is little doubt that Roy, in retirement, would have frequently remembered Indian cricket’s proudest statistical achievement—of which he was a partner

Mankad-Roy may be Dead, but their 413 Partnership lives on

Their names do not roll off the tongue together in the same manner as Hobbs and Sutcliffe, Hutton and Washbrook, Bill Lawry and Bob Simpson, and Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes. But Vinoo Mankad and Pankaj Roy achieved something that eluded even these legendary opening pairs, thus writing Partab Ramchand on the website Cricinfo. January 7, 2001, to be precise, was the 45th anniversary of their partnership of 413 runs for the first wicket, still the Test record.

It remains Indian cricket’s proudest statistical achievement. Now, with the death of Pankaj Roy, the two record makers are no longer with us. Mankad passed away in August 1978, and this could be an apt time to recall, by way of tribute, the background to that feat and how it came about.

Roy, of course, was a natural opening batsman and had served Indian cricket in that capacity since his opening test against England at New Delhi in November 1951. Mankad, on the other hand, had alternated between opening the innings and going in the middle order.

The two opened for the first time against England during the same series in the third Test opening stands of 72 and 103 (unbroken); their impact was immediate, and they seemed to have solved India’s quest for a successful opening pair. Mankad and Roy opened in the next test and were less successful with partnerships of 39 and 7.

The next time they opened together was against England in 1952. But after a partnership of 106 at Lord’s, they fell away with successive stands of 7, 4, 7, and 0. They opened again in the first Test against Pakistan at New Delhi in 1952–53, but the partnership was restricted to 19.

Madhav Apte briefly replaced Mankad as Roy’s opening partner in the West Indies in 1953. And in Pakistan in 1955, it was the turn of Pananmal Punjabi to partner Roy in the five-test. It did seem that the Mankad-Roy pairing, which initially promised so much, was to be seen no more. But the premature discarding of Apte and the failure of Punjabi brought the two together again in the first Test against New Zealand at Hyderabad. With Roy departing for zero, the stand was restricted to just one run.

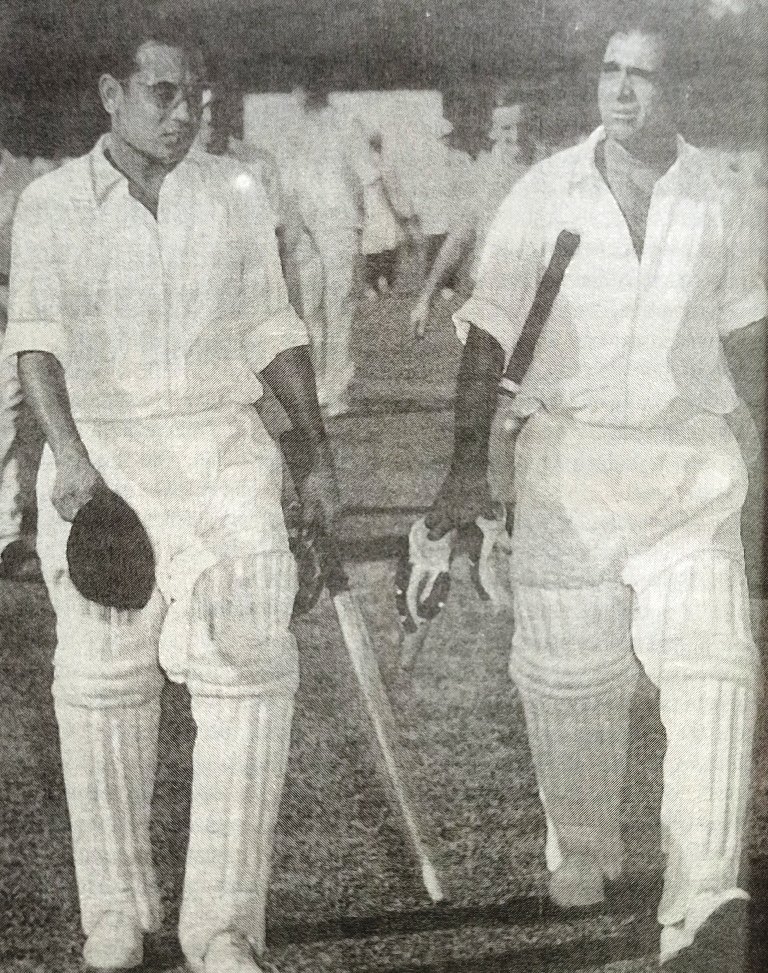

Three other opening pairs (Mankad and Vijay Mehra, Nari Contractor, and Mehra, Mankad, and Contractor) were tried out in the next three tests. For the final Test at the Corporation (later Nehru) Stadium in Madras, Mankad and Roy were back again. And on a pleasant morning on January 6, with the pitch ideal for batting, the two walked out to open the innings after Polly Umrigar had won the toss.

The New Zealand bowling had held no terror for the Indians, who had in successive Tests knocked up scores of 84 for four declared, 421 for eight declared, 531 for seven declared, and 438 for seven declared. John Hayes and Tony MacGibbon opened the bowling, but Mankad and Roy, sizing up the bowling and the pitch, made runs comfortably. In support, New Zealand had the medium-pacers of skipper Harry Cave, the off-spin of John Reid and Matt Poore, and the leg-spin of Alex Moir.

With conditions heavily loaded in their favor, Mankad and Roy brought up their 100 and then the 200. But as S. K. Gurunathan reported in the Indian Cricket Almanac, “it was by no means the best knock played either by Mankad or by Roy.

Both were hesitant in making their strokes, but there was no lack of concentration and determination to stay at the wicket as long as possible. Mankad now and again played his rousing pull shot and the drive to the off, but he rarely brought off his dazzling cuts.”

Pankaj Roy won the race to the hundred. He had batted 262 minutes and had hit only six fours. Shortly afterward, the Indian record for the first wicket, the famous 203-run stand between Vijay Merchant and Mushtaq Ali at Manchester in 1936, was passed.

Shortly before closing, Mankad reached his hundred in 287 minutes with nine fours. At close, India was 234 for no loss, with Roy on 114 and Mankad on 109. The two were the third pair of batsmen and the first for India to bat throughout a complete day’s play in a Test match.

The next day, the two continued where they had left off. Mankad overtook Roy and stayed ahead. They were still together at lunch, with the score now past 300 and now the sights—the record for all Test cricket by Hutton and Washbrook against South Africa at Johannesburg in 1948–49. This too was passed, and then came the 400, which was followed by Mankad’s double hundred on 359, his second of the series.

Hereabouts, so the story goes, Mankad and Roy received instructions from the pavilion to get on with it. Taking this as a hint that Umrigar wanted to make an early declaration, Roy tried to force the pace and was bowled by Matt Poore for 173. The partnership, which had realized 413 runs in 472 minutes, was finally over. For the record, Mankad went on to get an Indian Test record score of 231, and India went on to make a record total of 537 for three declared on their way to victory by an innings and 109 runs.

Since then, two pairs of opening batsmen have come to surpass the figure of 413. At Bridgetown in 1965, Simpson and Lawry put on 382 runs for Australia against the West Indies. Six years later, at Georgetown, New Zealanders Glenn Turner and Terry Jarvis put together a partnership of 387 runs against the West Indies. But after 45 years, 413 still remains the mark to beat for opening pairs in Test cricket.

Pankaj Roy, who scored 2,442 runs in 43 Tests and 79 innings, had been suffering from cardiovascular problems for the last few months. He was 72 years old. He was such a brilliant opening batsman, scoring a hundred on his Test debut as well. West Bengal’s first cricket legend, Pankaj Roy, passed away at Kolkata’s Anandalok Nursing Home in the early hours of Sunday, February 4, 2001.

On Saturday afternoon, he was admitted to the hospital, and in spite of a tireless effort by the group of physicians attending to him, the end came the next morning. He closed one of the gutsiest cricketing innings by a Bengal batsman. A person who had defied the odds, practicing facilities and vision problems early in his career, to tackle the likes of Roy Gilchrist, Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Brian Statham, and Fred Trueman.

Roy had three sons, the second of whom, Pranab, was doing duty as the manager of the East Zone side at Pune. The latter, however, managed to reach Kolkata in the morning. Those who turned up to pay their last respects included Sourav Ganguly, the former ICC Chairman Jagmohan Dalmiya, the former BCCI President Biswanath Dutt, contemporaries of Roy.

Like Premangshu Chatterjee, Kalyan Mittra, Chuni Goswami, former cricketers Gopal Bose, Palash Nandy, Sujan Mukherjee, Arun Lal, Ashok Malhotra, and the legendary footballer Sailen Manna. The Minister of State for Telecommunications, Tapan Sikdar, also visited the crematorium to pay his last respects.

Talking at the Cricket Association of Bengal (CAB), Premangshu Chatterjee, who made his first-class debut in the same match as Roy, said, “The game was against Uttar Pradesh. He scored a hundred, while I got seven wickets. Since then, we have been friends. However, even though he is three years younger than me, he managed to beat me to the pavilion of heaven.”

Jagmohan Dalmiya, who was also the President of the CAB, said, “It is an incalculable loss to the game of cricket. He was a man who symbolized courage.” Ganguly, who also garlanded Roy’s body, said, “I am too shocked to say anything really.”

From the office of the CAB, it was straight to the burning ghats. There, the three sons, namely Pradeep, Pranab, and Prabhat, amidst the chant of hymns, lit the funeral pyre. Then the body was pushed into the electric oven.

An era in Bengal cricket had ended. Sadly, the negligence that Ray revived on his last journey was appalling. It was only because of the enterprise of a couple of CAB officials that the funeral could proceed without any hassle.