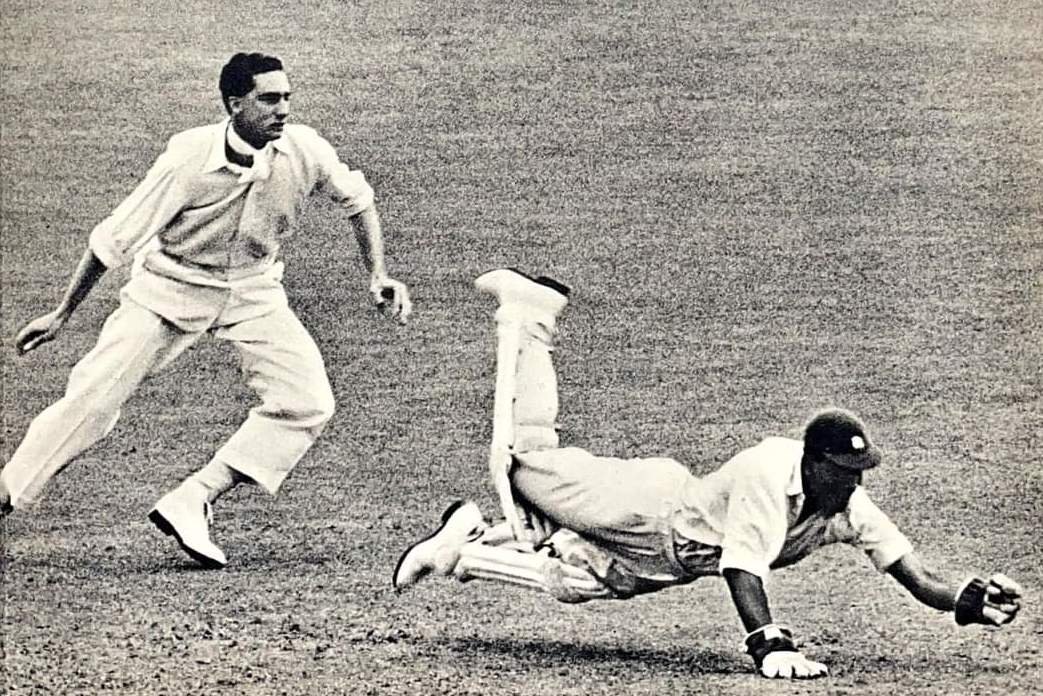

Among athletes known to me, only Joe Louis equaled the West Indian wicketkeeper, CL Walcott, in his ability to give an impression of soporific tranquility, instantaneously shattered by a spasm of action so fast as to be almost invisible and so conclusive as to be pretty well lethal to the enemy. Out of slumber, Louis floated to whip home his right hook, and out of slumber, Walcott sprang to stump the errant batsman or to slash the square cut to the fence.

With the deed done, both great athletes relapsed into apparent somnolence once again. Great cats couldn’t have uncoiled into action faster or more swiftly coiled back into repose. Walcott, six feet, two inches tall, was as fine a wicketkeeper as we saw in England during the season of 1950. The leading English batsmen admitted that it was impossible to detect whether Sony Ramadhin was bowling the googly or the leg break, but Walcott seemed to know.

CL Walcott kept both to himself and to Alf Valentine beautifully, perhaps never better than in the Second Test when he got rid of the first three English batsmen off these bowlers. Walcott hit seven centuries during the season, and hit is the operative word. He punched the ball on both sides of the wicket harder than Weekes—even harder, if less elegantly, than Worrell.

CL Walcott 168, not out in the Lord’s Test, contained 24 boundaries, mostly from drives. Among his major achievements at home are scores of 314 not out for Barbados against Trinidad in the 1945–46 season and 195–211 not out against British Guiana in a match made memorable by the fact that he also figured as the most successful bowler for his side.