During the 1950s and 1960s, Imtiaz Ahmad made his debut for the Pakistan national team in the position of wicketkeeper for the Pakistan national cricket team. With his exceptional skills behind the stumps, he played a crucial role in Pakistan’s early success in international cricket. He boasted a reputation for being one of the finest players in the world.

Imtiaz Ahmad played in 41 Test matches for Pakistan during his career, taking 128 catches and making 27 stumpings during that time. Besides being a useful lower-order batsman, he was also a useful lower-order wicketkeeper, scoring 2079 runs at an average of 29.45, and is considered one of the greatest wicketkeepers in Pakistan cricket history.

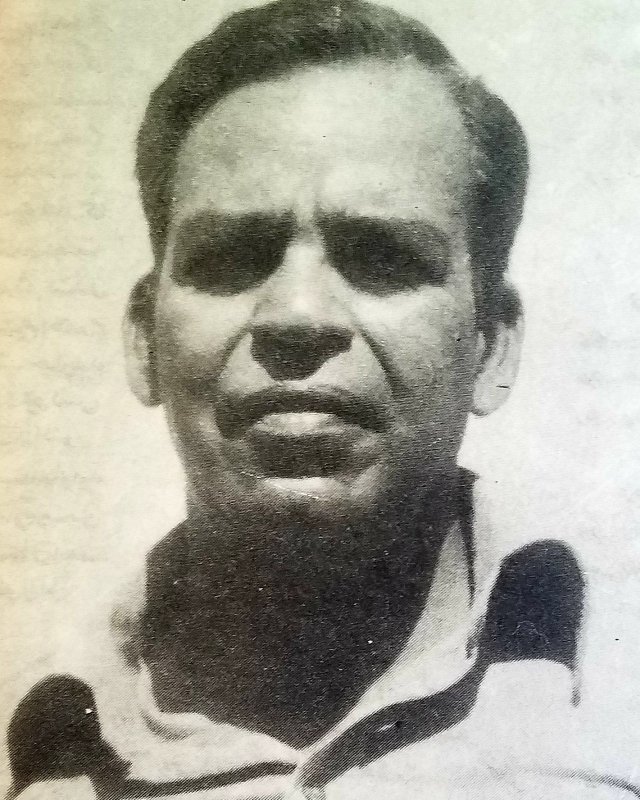

Whatever modern Test cricket may or may not be, everyone must recognize it as a serious matter. But when, as Pakistan was going down to defeat in the first Test at Edgbaston, Imtiaz Ahmed cranged Allen for six over the top of long-on, his wide grin suddenly invested even his side’s embattled position with the gaiety of a game. He epitomizes the approach of the 1962 Pakistanis.

In their desperately lean period, they were always making friends for two good reasons—though they were losing, they could always laugh and they could always hook up. Imtiaz has a military trimness—indeed, he is a Flight-Lieutenant in the Pakistan Air Force—but his laughter is infectiously boyish.

Like the rest of his side, too, he has an eager ability in the hook which could serve as a model for English cricket, where that vivid stroke has been all but outlawed. Bowl anything near short of a length near the line of his leg stump, and he is on it like a terrier on a rat, seeing and seizing the opportunity so quickly that he often hits well in front of square, sometimes almost to midwicket.

At 34 Imtiaz Ahmad is, by three months from Alimuddin, the oldest member of the Pakistan party and, with an appearance for Northern India in the Ranji Trophy of 1944-45 (before partition) when he was only sixteen, he is senior in first-class cricket to any of the England sides. Until a bout of malaria kept him out of the Headingley Test this month he held a record as unique as it was essentially fragile: he had appeared in every Test Pakistan has ever played.

Against England, Australia, West Indies, New Zealand, India—all the countries of the Imperial Conference in his time, except the politically proscribed South Africa—he has turned out in each of his country’s 39 matches. But, that precious record gone, he remains fit, capable, and keen: with luck, he might endure another six or eight years. His opponent is not another cricketer: as Dagley put it, a hundred-and-fifty years ago “Friend TIME Keeps wicket”. Still, Imtiaz Ahmad leaves some enduring imprints in the chronicles of the game. His favorite would be his century (103 in 83 minutes) before lunch for Pakistan against East Zone at Jamshedpur on the 1952-53 tour of India.

Imtiaz Ahmad has, too, made a score of 300 not out (for the Prime Minister’s XI against the Commonwealth XI) at Bombay, 1950-51—and a double-century in a Test-209 against New Zealand in the 1955-56 series. Statistically, however, his most impressive achievement lies, tantalizing, just ahead of him: he now needs only nine dismissals and 84 runs for 100 wicket-keeper-wickets and 2,000 runs in Test cricket. In the Edgbaston Test, he was the top-scorer for Pakistan and allowed no byes in the England innings of 544 for five. Four times—once against Australia and in all three against England, 1961-62—he has captained Pakistan.

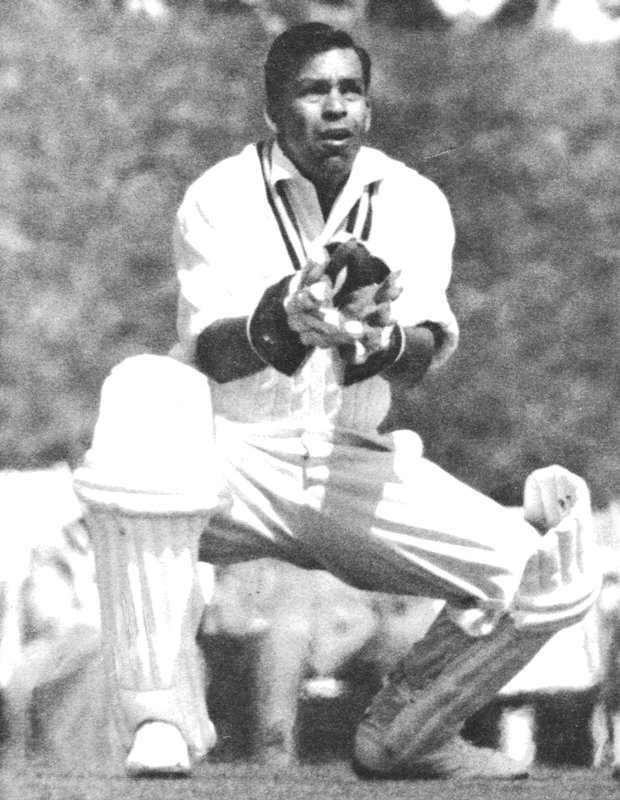

Over average height and leanly built, Imtiaz Ahmad lacks the compact shape which helps a wicket-keeper to look right. But he is extremely supple and has deliberately cultivated a low-keeping stance: quick on his feet and long of reach, he gets to some very distant thick edges and, especially, in the days when he kept to Fazal Mehmood, he took a crop of quick-dropping catches.

At one period Imtiaz Ahmad was regarded as only a stopgap wicket-keeper, and he is still a useful field anywhere, but his ambitions as a bowler give rise to more mirth than respect in the Pakistan dressing rooms: nevertheless, he has managed to “get on”, to send one over a maiden—at a Test bowler.

In a stronger batting side, he would have made his 2,000 Test runs long ago. Few men have been able to combine wicket-keeping with effective batting at the Test level. Imtiaz has had the added ill luck of being required to open the innings when he is essentially a middle-order batsman. He is, certainly, a good player of the new ball but he is at his best when he can play strokes from the start.

Then, especially against pace, Imtiaz Ahmad is a spectacularly aggressive batsman with a wide range of strokes but immense power on the leg side. In his own country he captains both the Services and North Zone sides, and, in 1960, he was awarded the Pride of Performance Medal and the Tamgha-i-Imtiaz.

In England, Imtiaz Ahmad will be remembered as one who took his cricket immensely keenly, even studiously, yet never lost his sense of humor about it and who, to his own and the spectators’ pleasure, used the bat as an instrument of lively attack.