John Hampshire first played for England in 1969 against West Indies at Lord’s. He was 28 years old. He made a century in his first Test innings.

Indeed, this is a rare feat, even today when there seems to always be a Test match pending or progressing somewhere. The only Englishmen who have done it are WG Grace, R. E. Foster, George Gunn, Iftikhar Pataudi senior (who was playing for England at the time) Griffith, May Milton, and John Hampshire. John Hampshire is the only one to have done it at Lord’s. There were several exceptional innings among these, with WG Grace setting the first home Test against Australia off to a resounding strut with 152 at The Oval. However, R. E. Foster made 287 at Sydney in 1903, which remained for more than a quarter of a century the highest Test score. Gunn’s 119 at Sydney in 1907, after he had been omitted from the original selection—he was in Australia ‘for his health’, and they had left out Hobbs to make room for him.

Griffith’s 140 in Trinidad in 1948 remains one of the most astonishing knocks in Test history only there because he was assistant manager and deputy wicketkeeper but was sent in first when the side suffered from numerous ailments. It was not only his first Test century; he had never made one in first-class cricket before.

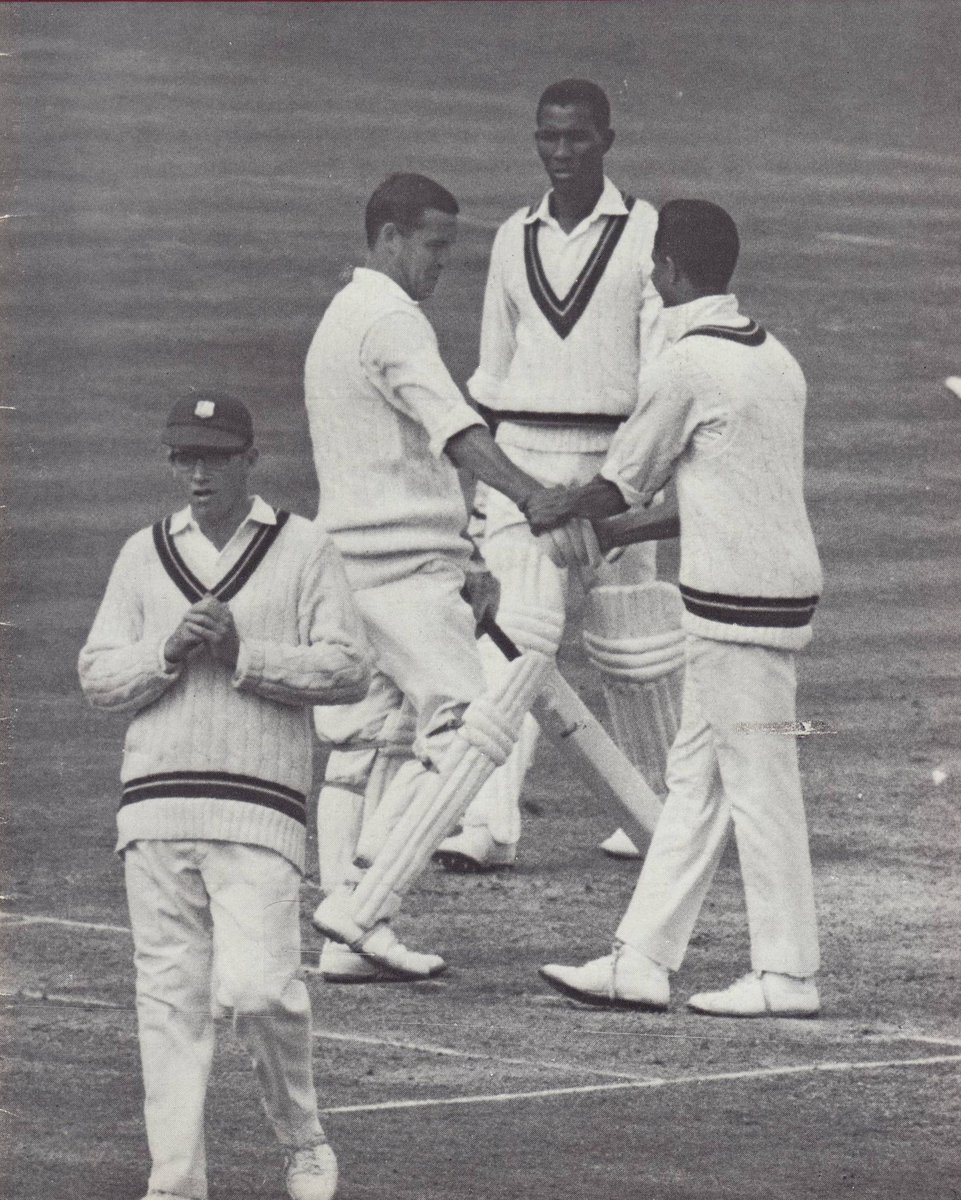

Yet none of these heroes had to face quite such a daunting prospect as John Hampshire when he went out to bat at Lord’s against West Indies. His selection had not been approved and Wisden wrote: ‘He had shown no decent Conn even this season and only got his place in the absence of Cowdrey, Barrington, Milburn Graveney, and Dexter.’ When he went in on Friday evening, the West Indies had scored 380 and England was 37 for 4—Boycott, Edrich, Parfitt, and D’Oliveria out. Soon on Saturday, Sharpe was out 61 for 5. The gates were closed, and at Lord’s, the sun was hot. Now was the moment for a man to make his reputation.

Shake a bridle over a Yorkshireman’s grave and he will rise up and steal a horse. Hampshire was seventh out at 249 for 107. Alan Knott had played well at the other end, and then Illingworth scored a century. It turned out to be a good match, although it was drawn. England was 36 behind with three wickets left at the end. The question that has to be asked about Hampshire after this magnificent beginning is, ‘What went wrong?’

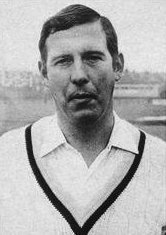

For here we are more than six years later and he is past the meridian of his career and has only played in seven more Tests. He lost his place in the England side after one more Test in 1969 and toured with the 1970-71 side, playing twice against Australia and twice against New Zealand. He was chosen once against Australia in 1972 and once more in 1975. He has never played an inning to compare with his first one but that can be well enough explained simply because his appearances were so intermittent because he was always playing for his place and always under stress. Why has he never had a regular place?

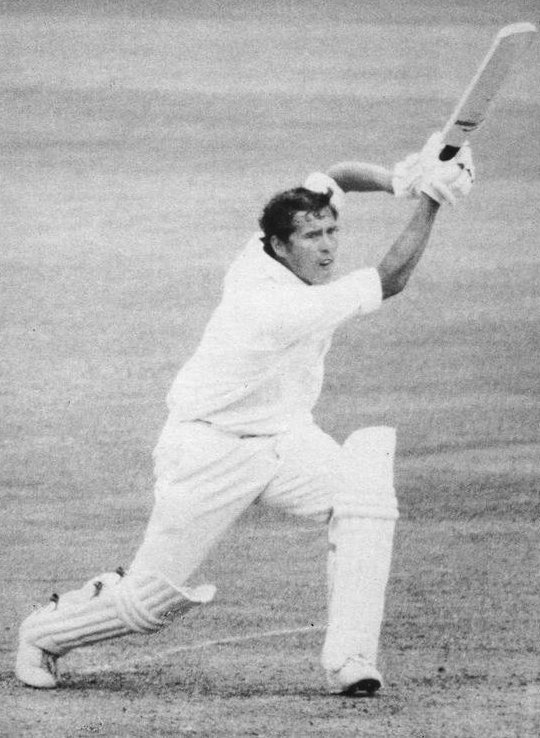

There are broadly two answers to this question, and you can usually tell from which part of England your respondent comes from the one he chooses. In the north and, naturally, in Yorkshire, they say, ‘Bad selection. I never gave the kid a chance to settle in. In the south, they say. ‘Not quite good enough’. There is no doubt that when he is going well, he is a commanding player and one of the best-looking English batsmen we have seen in the last fifteen years. His cover drives, straight or to the off, are noble strokes. He can also force the ball well, though I am never quite so happy to see him hitting in that direction because his bat is inclined to be crooked.

I have seen him cut with great power. He is a strong man. Bill Bowes has written of him, ‘He is so powerful that he can mishit for four’. But the question about Hampshire turns to his technique, which is more widely admired than his mental approach. So often, he has seemed to lose concentration at a point in his innings when he should have been taking control.

I remember that before the beginning of the Leeds Test last summer there was some discussion in the commentary box about the choice of Hampshire, and if I remember rightly, he had only at that point scored 22 centuries in his first-class career, which over fifteen years is not Op to the mark for an England No. 4. Fletcher’s record, in aggregate average, and centuries, is substantially better, though that was not a point at which it was wise to labor at Headingly. I have heard it said, even by Yorkshiremen, that Hampshire does not think enough about the game.

I have heard Trevor Bailey describe — I hope I have got the details right—how he first bowled to him. Bang and a good-length ball went screaming along the ground for four between cover and extra. He said, Trevor, it looks as if we have something here: and bowled the next one a flute wider and allure slower, and a title shorter (you have to hear Trevor saying those ‘titles’. opening his fingers about half an inch to demonstrate the distance involved) and hang, thank you very much, taught at extra cover.

Understandably enough in a young man, but it is the kind of cheerful casualness that an experienced cricketer ought. I suppose to conquer: at least if he is going to be a Test batsman. Nevertheless, there is no denying that such criticisms have some substance. I share the view of most Yorkshiremen that the selectors should have persevered with Hampshire more than they have done. He had shown throughout his form on that day at Lord’s in 1969 that he could rise to an occasion.

If they ignored his county form, then they could equally well have done so later. ‘there are some players for whom county form means little when it comes to a Test match, and several of them have been Yorkshiremen: Maurice Leyland, Willie Watson of Leyland Cardus wrote that he was ‘always an England batsman: for the purposes of Teal matches, he should be regarded as in form whenever he is not suffering from a broken leg or a splintered finger’. I do not suggest that Hampshire has ever been in the Leyland class, but if Leyland had been given so few and scattered opportunities, he might not have done much better.

John Hampshire is a genial companion, popular with his fellow cricketers. He has been known to bowl leg-breaks, and I once saw him take 7 for 52 against Glamorgan at Cardiff, about a quarter of the wickets of his career. He is a fine fielder. When he and Shame were together near the wicket, Rinks was behind it and Close was somewhere about it, there was no place for snicks. Now, Sharpe, there was another lad by the groom who, if there were any justice in the world, was a horse or, anyway, a bridle of another color.