Blast from the Past: Karsan Ghavri is a self-made all-rounder. The grim irony about our seemingly futile search for pace bowlers is our inability to spot and encourage talent right under our noses. Karsan Ghavri is a case in point. He has been hailed as one of the “discoveries” of the recent series against the West Indies, yet he has been providing ample evidence of his potential for at least three seasons now.

And he may not have been discovered at all had India’s defeat in the first two Tests by stunning margins not underlined the need to bolster our spin attack with pace. Judged by figures alone, Karsan Ghavri performance in the last three Tests could by no means be termed spectacular. He had a haul of nine wickets for 316 runs off 444 balls and scored 87 runs at an average of 17.40.

Yet his runs and wickets came at critical stages, and on the field, he was a positive asset. On his debut at Calcutta, he was an admirable foil to Madan Lal, and he was also concerned with a valuable stand of 91 runs, which materially improved India’s prospects in the match. And when our spinners were getting the big stick again in the final Test in Bombay, it was to Ghavri that skipper Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi turned to keep down the runs as well as the over-rate.

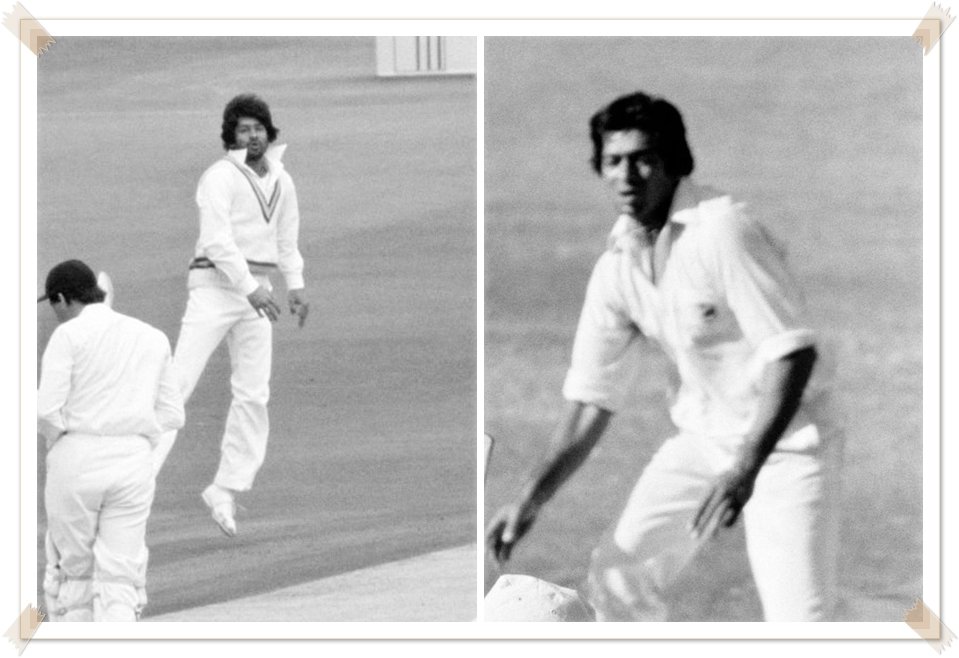

Manager Gerry Alexander was probably judging him by West Indian standards when he said at the end of the series that Karsan Ghavri figures were “overrated,” but for Indians, it must have been a sight for sore eyes to watch a quickie ‘in action for long spells and troubling the batsmen. He had most of them, including Clive Lloyd, edging or beaten, and would have had more than four for 140 had our close-in fielding been sharp.

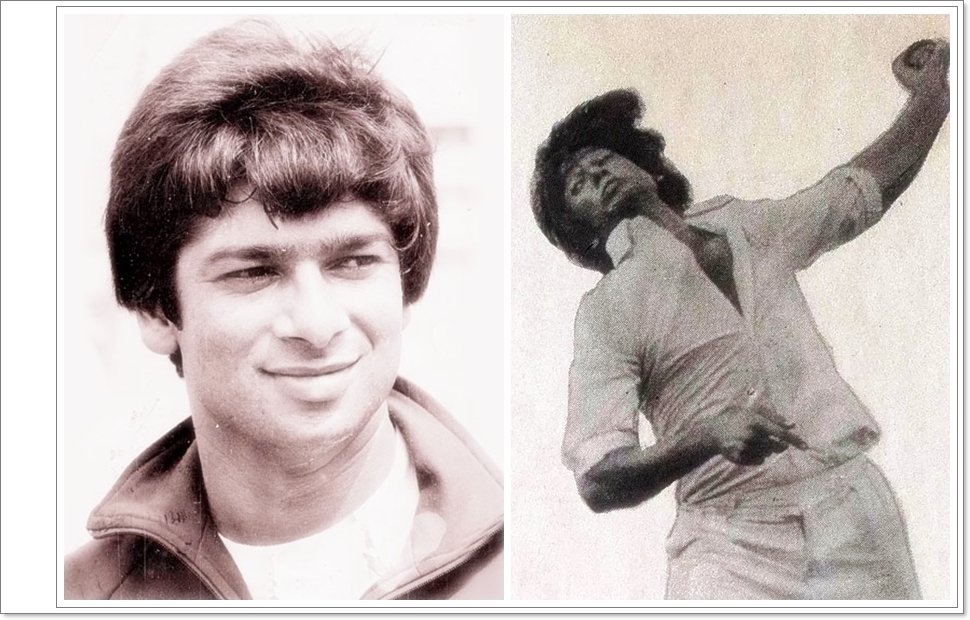

It would perhaps be more accurate to describe Karsan Ghavri as an all-rounder rather than a pace bowler, though it is as a quickie that his services are needed most at the Test level. He doesn’t have the fearsome looks of a fast bowler, nor is he endowed with blinding pace. Yet the amiable, 5 feet and 11 inches with a 72 kg weight from Rajkot are pretty effective at a lively medium pace and with his ability to angle the ball towards the slips 7 or make it get up from just short of a length.

As a batsman, he is a handsome striker of the ball with sweet timing. He scored a sparkling 79 not out, including two sixes and ten fours, to scotch MCC’s hopes of a victory over West Zone at Ahmedabad in 1972-73. Like most left-handers, they’re natural players.

Karsan Gharvi first unfolded into my view during the All-India Schools Tournament at Bangalore in 1968–69. Reviewing the competition for the 1969 edition of “Indian Cricket,”

I said, “In view of the country’s dire need for a genuine pace bowler, the stock on view at Bangalore came as a bitter disappointment. Yet, when I look back on the twelve days of the Cooch-Behar competition, the strongest image is that of Karsan Gharvi, who bowled at a lively medium pace. “Tall and wiry, the Saurashtra left-hander struck me as the most outstanding of the new crop.

Karsan Ghavri diagonal run-up always helped him to make an easy delivery, a nip of the pitch, and the way he made the ball hurry across the bat all reminded me of Alan Davidson. Like the Australian, he never flagged. In just two matches for West Zone, Ghavri had a haul of 15 wickets for 127 runs. His nine for 59 in the final against East Zone was the best match analysis in the tournament.

One hopes he will rise to the same stature as his famous competitor.” On the tour of Australia that immediately followed, Ghavri was an outstanding success. He was second on the batting list with a tally of 564 at an average of 43.38, and he took 28 wickets for 636 runs.

Noted manager Hemu Adhikari: “Though these bowlers did not trouble the Australian batsmen much, they successfully pinned them down and bottled up the scoring. “The averages do not reflect a high caliber of wickets by these bowlers, but they invariably succeeded in breaking through the initial batsmen,’leaving to the inners the task of dismissing the middle-order batsmen.

He also stated, “He (Deepankar Sarkar) was well supported by the other spinners and by Ghavri, an opening bowler, who, occasionally, was used as a natural leg-spinner.” He also bowled an effective “china-man.” Fortunately, Ghavri stuck to an honest, medium pace, despite its rigors and lack of rewards. One “accident” did not cancel out; ‘another made him switch over from spin to speed while a seventh-standard student at Virani High School.

He was entrusted with the new ball in the absence of the regular opening bowler, and he claimed seven wickets. His principal, J. Acharya, obviously knew his cricket and strongly urged the youngster to continue hurling the ball with all the speed at his command.

Karsan Gharvi played for Saurashtra in the Ranji Trophy soon after his return from Australia. After that, he migrated to Bombay (now Mumbai) more in search of bread and butter than to showcase his talents.

His first real break came when he was included in the Indian team for the tour of Sri Lanka, where he found his girl, but, in the face of competition from Salgaonkar and Madan Lal, few opportunities to show his skill.

He was left out of the side for England, but his consistently good performances at home had clearly marked him out as a Test prospect. His bow at Calcutta thus came not a day too soon; Ghavri, of course, isn’t another Alan Davidson. He has miles to go before he can acquire the sustained hostility and infinite guile of the famous Australian.

His chief assets at the moment, as I said, are his ability to angle the ball towards the slips and make it rise disconcertingly. He can perhaps be at least a yard or two faster should he iron out” his delivery stride. He tends to slow down a bit; his weight is slightly forward at the moment of delivery, and he doesn’t make maximum use of his height.

But he ‘has the talent all right. With a little more effort on his part and guidance from others, he should serve India well. In the course of a chat, I asked Ghavri whether he did any physical training. Do you mean exercises? Of course, I do some running and skipping.

When I suggested weight training to strengthen his back and shoulders, he betrayed a common fallacy by saying that “weight-lifting tended to stiffen one’s muscles. I explained to him as best as I could that weight training ‘and weightlifting were two totally different things. Ghavri is self-made.

All the coaching Karsan Ghavri has received consists of tips from his uncle, J.M. Ghavri, who has played for Saurashtra, and from Adhikari during the school’s team’s Australian tour. So long as our young hopes have to fend for themselves, the search for pace bowlers will remain futile.