The art of reverse swing bowling is popular these days. On the subcontinent, although there are exceptions, especially in Pakistan, the atmosphere during a cricket season is dry, and the wickets have barely any grass on them. As a result, lifting the seam or applying substances to the ball to enhance the orthodox swing—the two illegal, but almost accepted, methods used elsewhere—are pretty ineffectual.

In these conditions, we have this phenomenon that was, until recently, unheard of in England: “reverse swing.”. In other words, instead of a ball swinging the orthodox way—i.e., opposite to the shine—it swings with the shine. Because of the rough outfields and grassless pitches, the balls lose their shine quickly, and the leather gets scuffed up.

By applying a lot of sweat and shine to one side and leaving the other side rough, the ball will swing towards the shining side. It is nonsense to say that reverse swing bowling can only be obtained by ball-tampering. On certain rough outfields and dry pitches, by the time a fast bowler comes back for his second spell, the ball is rough enough for a reverse swing.

In Australia, because of the nature of the wickets, which become dry and rock hard by the fourth and fifth days of Test matches, even during the first spell the ball gets so roughed up that it takes a reverse swing. In 1976, at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, I saw Dennis Lillee, in the second inning, move the ball with great devastation.

A couple of years earlier, Max Walker, whose home ground was the MCG, wrecked the West Indies in Guyana with a reverse swing. Even earlier, Freddie Trueman had written in his book about this occasional anomaly when the ball swings with the shine.

Reverse swing was unknown in England until 1981, when the TCCB made changes to the balls. Before then, with the much bigger seams—and on wickets that were never as bare or as hard as in Pakistan or Australia—it was virtually impossible to produce a reverse swing. Moreover, the lush green outfields preserved the ball even when it was 100 years old.

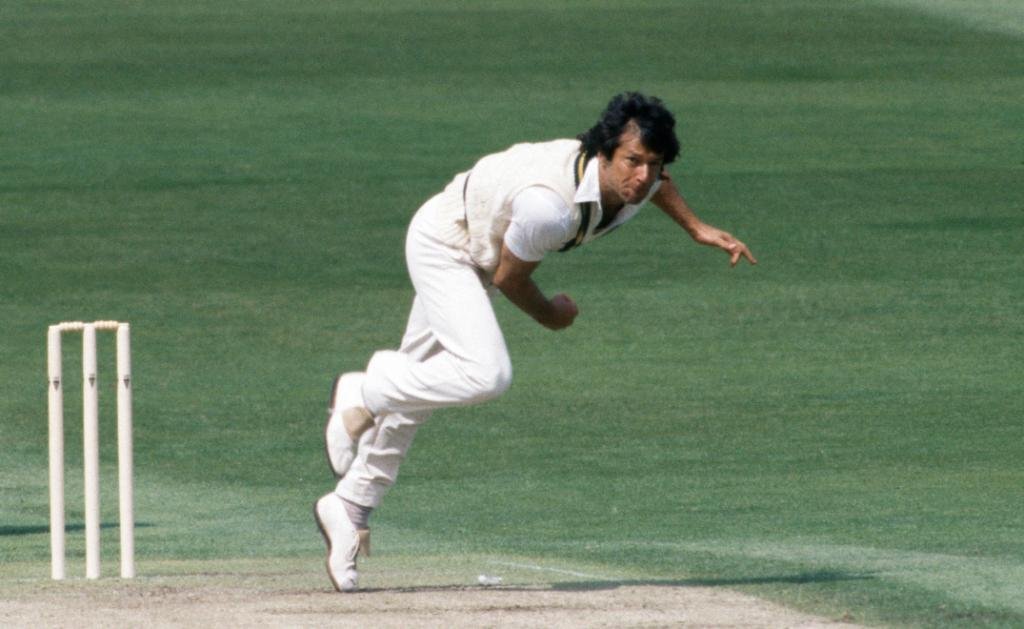

Only in August, during dry spells, could I bowl reverse swing. After 1981, suddenly the ball began to swing much less in the orthodox fashion, and the leather somehow tended to get scuffed up much quicker. From mid-July to the end of August, when the outfields and the squares became well worn, I regularly used reverse swing after the ball was 40 to 50 over’s old.

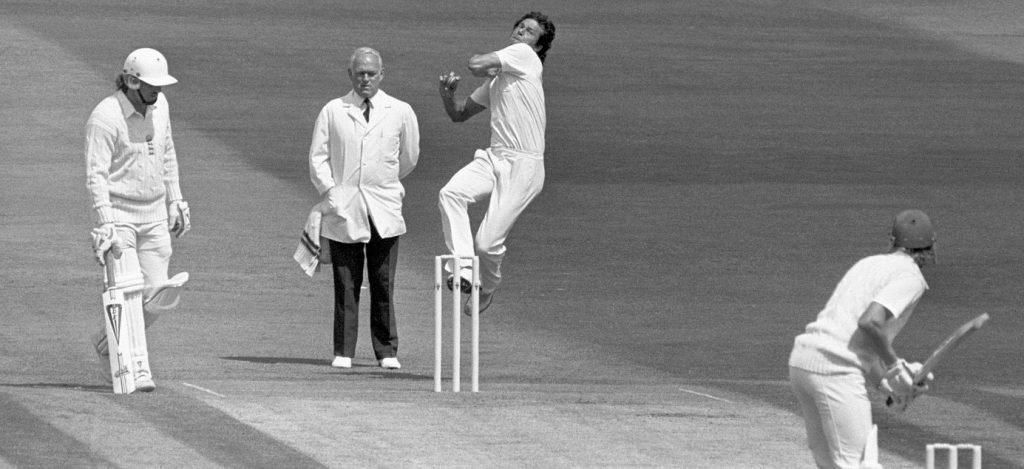

Of course, I had to tell my Sussex colleagues—much to their bemusement—to preserve the rough side rather than the shining side. In August 1982, on a rough Lord’s Square when Pakistan was playing England, the ball got scuffed up within a few overs. While we were bowling reverse swing, the English bowlers were unable to get any movement at all.

There was some innuendo of ball-tampering after the match, even then. The thing about reverse swing is that not everyone can do it. One must have the ability to swing the ball in the first place. Secondly, it takes a while to perfect the delivery, as the ball is gripped and released differently. In 1990 in England, the seam of the ball was further reduced by the TCCB, and since then, reverse swing has been quite common in county cricket.